|

"Not using a quarantine tank is like playing

Russian roulette. Nobody wins the game, some people just get

to play longer than others." - Anthony Calfo

I

found this statement to be quite poignant in its simplicity

and accuracy in summarizing the necessity of quarantining

animals in the reef aquarium hobby; or, better yet, the folly

of not using a quarantine tank. If you talk to a group of

industry professionals and experts and ask them for one thing

that could help to make or break an aquarist's experience,

the advice to quarantine one's livestock is likely to be a

popularly expressed opinion. In fact, many authors on aquarium

keeping have, in their own books, advocated quarantining (Borneman,

2001, Calfo, 2001, Delbeek & Sprung, 1994, Fenner, 1998,

Paletta, 2001, and Tullock, 2001). Take another look at that

list of authors. It is a veritable "Who's Who" of

marine aquarium keeping. And, those are just the ones from

whom I could find a reference regarding the importance of

quarantine. I am sure other respected authors and individuals

also advocate quarantine, but I simply didn't have their book

or article in my library.

Probably no one piece of technology or type of methodology

separates the successful, long-term aquarium hobbyist from

the hordes of individuals who have aquariums collecting dust

in storage, or are trying to recoup some of their costs from

a failed marine aquarium adventure at garage sales, more than

the use of quarantine. The purchase of a tank and associated

equipment for use as a quarantine facility is one of the simplest

and most inexpensive investments one could make in the safety

and well-being of our aquatic pets. Yet the use of a quarantine

system is one of the most often underrated or improperly applied

methodologies in the hobby. Please note, I am not talking

about just fishes here. I would urge aquarists to quarantine

everything added to their tanks that could possibly carry

a pathogen or pest, or that needs extra care: fishes, motile

invertebrates, corals, live rock, live sand, etc. Basically,

anything that is wet should be quarantined. In this article,

I hope to demonstrate the merits of quarantine (and supplementary

preventative treatment when necessary) and also to demonstrate

an inexpensive model for hobbyists to use to properly isolate

their new acquisitions while keeping them healthy.

The Good:

There are several

reasons to employ a quarantine tank. The first and foremost

is disease prevention and treatment. While some hobbyists

may argue that Marine Ich is always present, or that all that's

required is a healthy display and the fish's own immune system

will take care of any disease, the fact is these opinions

are just that - opinions. They are not supported by science.

Truth be told, I used to believe the first, that Marine Ich

is always present. It was aquarium folklore that was passed

down to me and I bought into it. That is, until I did some

independent research into Cryptocaryon irritans, the

pathogen known as Marine Ich. First, Cryptocaryon irritans

is an obligate parasite (Dickerson & Dawe, 1995), meaning

it cannot live without a fish host. Second, Cryptocaryon

irritans can be killed by a number of scientifically proven

methods (Noga, 2000). If this parasite is never introduced

into a tank, then susceptible animals can never get infected.

All the stress in the world cannot make a parasite magically

appear out of nowhere. A proper quarantine protocol allows

time for any diseases to progress to the point when they are

noticeable and hopefully identifiable. This isolation period

also permits the hobbyist to treat the disease with the best

course of action without a concern for collateral damage to

the sensitive life found in a healthy reef or a fish-only

with live rock (FOWLR) display. And last, it allows for the

option of prophylactic treatment of animals that are commonly

infected with certain diseases.

But, disease prevention and treatment are not the only benefits

of quarantine. If a fish is sick, the period in a quarantine

tank allows that specimen time to recover from the ailment

and its aftereffects. Sick fish often refuse to eat. This

is often one of the first signs that something is wrong with

an animal. A quiet, protected environment, free of competing

animals is a perfect place for a recovering animal to put

on weight, rebuild its fat reserves, and allow for any damaged

tissue to heal (such as open sores from parasitic attachment

points or ragged, torn fins). And, the fish does not have

to be sick to benefit from this quiet time. Fish that have

endured the rigors of transport and of making their way through

the chain of custody from the reef to the home aquarium can

use some tender loving care. In some instances, it might have

been days or weeks since they had been fed or had accepted

food that was offered. Remember, the food items we offer are

unnatural. It takes time for the fish to become accustomed

to prepared foods. Many grazing fish, like Angelfish and Tangs,

have evolved to constantly scour the reef substrate looking

for food. The aquarist should expect that it will take some

time to train them to look up for food and to recognize that

the debris raining down from above is actually edible. Throwing

a malnourished fish into a display tank where it must immediately

compete with the current occupants for territory and food

is not a recipe for success, in my experience. On the other

hand, fattening up a new acquisition before introduction to

the main display greatly increases the odds that it will be

able to effectively vie for space and food when placed into

its new home.

|

Fish in such a condition as this Maroon clownfish would benefit

greatly from some time

alone in quarantine to recuperate. Photo by Steven Pro.

Many of the same benefits that fish can derive from a quarantine

period also accrue to the animals we collectively refer to

as 'corals.' Just like fish, corals can harbor pests and pathogens.

Placing these specimens in isolation allows for close, careful

observation and screening for potential problems without needlessly

exposing the rest of the main display. It also gives the colony

some time to recover from shipping stress. If you have never

imported corals, let me assure you there are anomalous losses

from the trauma of being stuffed into a relatively small shipping

bag, then kept in the same minute volume of water in complete

darkness, while exposed to the elements and "gorilla"

airline freight personnel. Many LPS corals suffer from tissue

abrasion and subsequent secondary infections due to banging

into the sides of a plastic bag for extended periods. Euphyllids

are particularly prone to this condition. Also, Xeniids commonly

"melt" after shipping, plausibly because of the

trauma of transit. Some sponges can get air trapped inside

their tissue and rot from the inside out. The list goes on

and on, and I for one would rather have any rotting, necrotic

tissue confined to the safety of a quarantine system than

introduced into a display tank where an influx of nutrients

and toxic metabolites from the decay could foster nuisance

algae at best, or perhaps foster bacterial infections among

other susceptible display animals.

The Bad:

Let's take a brief

moment to mention the staggering variety of pests, predators,

and pathogens that one wants to avoid importing with a new

acquisition. For fish, the most common diseases are parasitic

and can easily destroy all fish in a tank in days to weeks

if left untreated. Furthermore, most of these cannot be consistently

dealt with in a natural-style display (in the presence of

live sand, rock, invertebrates, etc.). Some people have had

luck using various homeopathic or allegedly reef-safe medications,

but none of these have been demonstrated effective, and not

even the anecdotal reports of success are consistent. Sometimes

it appears they work, other times they don't seem to make

a difference at all. Cryptocaryon irritans (Marine

Ich) and Amyloodinium ocellatum (Marine Velvet) are

the two most commonly encountered parasites, and either can

wreak havoc on a system. Many others are less frequently encountered,

but aquarists should still look out for: Brooklynella,

Turbellarian worms (Black Ich), Uronema, and various

types of flukes, to name just a few.

|

|

Damage

on a beautiful coral, Pocillopora sp. (left),

caused by a Coralliophilid parasitic snail (right)

that most likely hitchiked into the aquarium with some live

rock. Photos courtesy of Graham Stephan (Pineapple House).

In the case of invertebrates, the water used to transport

them from the store to the display aquarium could harbor free-swimming

stages of fish parasites. Hermit crabs or snail shells could

be a way for the cysts of these same parasites to hitchhike

into a display tank. Again, it is better to be safe than sorry.

Quarantine these animals.

Two common pests typically imported via live rock: Left:

Aiptasia sp. Right: Anemonia majano.

Photos by Steven Pro.

|

|

A Cirolanid isopod. Photo courtesy of John Loose (lllosingit).

|

Live rock can harbor an array of undesirable creatures. Again,

the tomont stage of fish parasites like Cryptocaryon

or Amyloodinium could hitchhike in unquarantined live

rock. In addition, the nuisance anemones Aiptasia and

Anemonia majano are commonly imported this way, as

are, to a lesser extent, pests such as flatworms and some

nudibranchs. And finally, with the ever-increasing popularity

of aquacultured live rock from the Atlantic, we are beginning

to see an increase in the appearance of pests such as Cirolanid

isopods (photo left), mantis

shrimp, and the large Caribbean fireworm (Hermodice

carunculata). While I very much approve of aquacultured

rock because of the abundance and diversity of creatures that

come with it, as well as for conservation reasons, these are

common issues with this substrate. Along with the good comes

some bad, and one must be prepared to deal with it and the

easiest way is by using an isolated quarantine tank, rather

than in the main display.

|

|

A predatory nudibranch seen here consuming polyps on a Montipora

digitata.

Photos courtesy of Skip Attix.

This unfortunate Amphiprion ocellaris is the victim

of an attack from several Cirolanid isopods.

Photo courtesy of John Bass (NoobieNemo).

|

|

A mantis shrimp can wreak havoc on many inhabitants

of a typical reef aquarium. Photo courtesy of James

Fatherree.

|

The organisms we collectively refer to as 'corals' also have

their fair share of potential risks if added to a system without

a quarantine period. Small polyp stony corals, in particular

Acroporids, could undergo the contagious shut-down reaction,

better known by its acronym, RTN. Aquarists must also watch

out for the red Acropora copepods, ciliates, flatworms,

hydroids, or even parasitic snails on various SPS corals.

Large-polyped stony corals, like the Euphyllids, routinely

suffer from the so-called "brown jelly" infections

upon importation, also common following tissue damage. Various

predatory snails, like the Pyramidellid snails

with Tridacnid clams or the box snails with zoanthids, also

hitchhike into our tanks. Additionally, flatworms or coral-eating

nudibranchs (the ones associated with Montipora

seem to be rather 'popular' these days) could be hiding in

and amongst that newest acquisition awaiting the smorgasbord

that is your beautiful reef display. Even soft corals bear

parasites and unwanted predators, such as flatworms, nudibranchs,

and mollusks that are often well disguised in mimicry of their

host corals. Similarly, zoanthids carry the small and cryptic

sundial snails that consume their host polyps. In my opinion,

it is much better to be safe than sorry. Quarantine all these

animals, too.

|

|

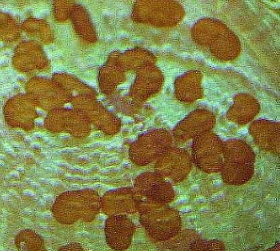

Left: I don’t know if I would consider this an

Open brain coral with a flatworm problem or a flatworm colony

with a coral problem! Right: a close-up of the flatworms.

Photos by Steven Pro.

Left: Powerful stinging hydroids, while not as prolific

as Aiptasia, can still be problematic in a reef tank.

Right: a close-up of the hydroids. Photos by Steven

Pro.

And The Ugly:

Let us assume for

the moment that after having decided to forgo a proper quarantine

period and instead placing questionable livestock into the

display, it is now contaminated with some pest or pathogen.

What are you going to do then? Having chosen not to quarantine,

it is highly unlikely that the aquarist is prepared to quarantine

after the fact. The mistake has already been made and some

undesirable organism has been permitted to infest the display.

Instead, the problem is often exacerbated by the use of some

wonderful medication that is alleged to be 'reef-safe'. I

have never understood the meaning of this term. Has the manufacturer

conducted extensive toxicology tests to prove that this drug,

at its recommended concentration, will not adversely affect

the myriad of life that is present in a mature reef display?

If it has, I have never seen any of the test results published.

Furthermore, I have not seen many manufacturers publish data

demonstrating that their products are even effective, let

alone safe. Do aquarists actually consider exacerbating the

problem by utilizing unproven and potentially dangerous drugs

to affect a cure? Let's hope this course of action is not

chosen. Instead, quarantine and treat the infected individuals

and any other potential hosts while allowing the display to

go fallow (without any hosts) until the pathogen or pest population

dies out. In many instances, one to two months should suffice.

In some cases, like Cirolanid isopods, three

months may be required (Shimek, 2002). But, that is not an

argument against this course of action. On the contrary, it

is a strong argument to have and utilize an effective quarantine

protocol in the first place.

|

|

Aeolid nudibranchs on a plating Montipora sp. Left:

A close-up. Right: The eggs can be clearly seen

in this photo. Photos by Adam Cesnales.

Pyramidellid snails (the small specks on the right) preying

upon on a Tridacna derasa.

Photo by Adam Cesnales.

I am also reluctant to add anything to my display, be it

a medication or an alleged beneficial supplement, unless I

know three things: 1) what it contains, 2) if it been proven

to work, and 3) it is it really needed (the best solution)?

The first one is easy enough to verify. Does it have a list

of ingredients? If not, I won't even consider using it. The

second qualifier is also easy to check. Have there been published,

peer-reviewed data to support the manufacturer's claims for

marine species, or even any other species for which the mode

of action has some basis? If a supplement is not proven to

be beneficial or a medication not demonstrated to work, again

I pass. Last, can I verify the concentration in my aquarium?

Supplements like calcium, magnesium, and alkalinity pass all

of these tests. Manufacturers list the contents, it can be

proven that they are necessary, and they can all be tested

to confirm or correct the dosage given. There are also treatments

that can jump these hurdles, such as hyposalinity and copper.

On the other hand, I am unaware of any alleged 'reef-safe'

treatments that come with a test kit or have been proven effective.

There are also several products that I like to refer to as

"magical elixirs" that don't even list what is in

them, let alone prove that they work or that their target

concentration is available.

|

The author's medicine chest (from left to right): Seachem’s

Cupramine and copper test kit, Epsom

salt for mild cases of Pop-Eye disease, a battery of Salifert

test kits for monitoring water

quality, a refractometer used for hyposalinity treatments,

formalin, garlic, and

Metronidazole. Photo by Steven Pro.

The Quarantine Tank:

When selecting an

aquarium to use as a quarantine vessel, there are only a few

things to consider. First, it must be proportional in size

to the main display tank. If the plan is a 180-gallon reef

display that is to be teaming with surgeonfish, a 10-gallon

tank as a quarantine tank for fishes is probably a bad choice.

Alternatively, if you have only a 55-gallon tank and you are

a conscientious aquarist, there are few fish that could not

reasonably be kept in a 55-gallon tank for their entire life

that couldn't be maintained in a 10-gallon tank for one month.

If a 150-gallon or larger tank is used for a display, consider

purchasing a 30-gallon or larger quarantine tank if the larger

display is to house larger-sized animals. Generally, aim for

a quarantine tank that is at least 20% of the main display's

volume, although bigger would be better.

|

|

The author's quarantine tank is intended for fish only,

but with a few PC fixtures standing by it can easily

be used for quarantining photosynthetic plants and animals.

Photo by Steven Pro.

|

Another consideration for quarantine tanks is depth; the

shallower the better as long as the depth is great enough

to cover the intended quarantined livestock. This relates

specifically to lighting for when quarantining photosynthetic

plants, animals, or live rock. It is far easier and less expensive

to light a shallow vessel than a deep one. For this reason,

forgo the tanks designated in the trade as "high"

or "extra high." Shallow aquaria also have added

benefits for dealing with fish in quarantine. They generally

have more square inches of surface space per gallon than the

same size tall-style aquariums. This greater surface area

does two things. It allows better gas exchange and therefore

higher levels of dissolved oxygen (something that can be crucial

in small aquaria) and a long, shallow tank has more swimming

space for confined fishes.

I also prefer to use an actual glass or acrylic aquarium

rather than containers of opaque material because it allows

easy viewing and monitoring of the things in isolation. Food-grade

rubber and plastic tubs (like the type found at Wal-Mart or

similar stores) can be used, but these are generally opaque

or colored, making observations difficult. This, too, is a

matter of proportion. If the aquarist has a display that costs

thousands of dollars, perhaps tens of thousands of dollars,

what is a couple of hundred more to ensure the overall health

of the system? Dismantling an existing display, loss of livestock,

and the purchase of various treatments can quickly exceed

the cost of a simple quarantine system. If the additional

cost is a concern, search through the local newspaper, which

usually lists several used aquariums for sale. Garage or yard

sales are another place where a real bargain can be had. A

large number of people (who probably killed all their fish

because they did not recognize the importance of quarantining)

are always leaving the aquarium hobby, definitely making this

a buyer's market.

Finally, I prefer to use a background to cover the back and

two sides of the tank. This keeps the aquarium a bit more

subdued and seems to calm the quarantined fish a little more

than if the movement from activity in the house is visible

from all four sides. It is not really a hard and fast rule

or a proven methodology, but intuitively it makes sense. I

also paint the bottom of the tank because I don't use substrate

in my quarantine tanks. This seems to stop reflections and

appears to add to the fishes' comfort level.

Filtration:

Most individuals that

have quarantine tank problems are either unprepared or uneducated

in what a proper quarantine tank's filtration must do. There

must be some sort of fully functioning, cycled biological

filter. Many times I have read of hobbyists who merely remove

water from their main display, add a brand new or sterile

filter, and think they are ready to go. They are often surprised

by their subsequent ammonia trouble and its impact on their

new acquisitions. There is nothing magical about aged water.

Some small quantity of beneficial bacteria may be free-floating

in the main aquarium's water, but it is not enough to sustain

an ammonia-free environment in a newly established quarantine

tank. Ammonia and/or nitrite poisoning is a real risk in quarantine

tanks (really for any tank, for that matter, that does not

have an adequate biological filter) if the aquarist is unprepared.

I am of the opinion that most people who fail with a quarantine

tank, fail because they overlook or misunderstand this key

aspect.

I don't want to discourage people from using water from their

display to fill the quarantine tank; this is a sound practice.

Aged water is much less harsh than freshly mixed artificial

seawater, and results in an easier transition for the new

animals to adjust. However, it simply does not take the place

of a good biological filter.

For simple biological filtration in a quarantine setup, I

prefer air-driven sponge filters. These can be found at just

about any aquarium store. They are very effective and inexpensive,

although admittedly unattractive. If there is a sump on the

main display, I would encourage the aquarist to place at least

one small sponge filter there and keep it running at all times.

This way, when the need arises, there will be a functional

biological filter ready and waiting. While the nitrate produced

by this unit may concern some, it should be of small consequence

to most mature displays. With the increasingly common combined

use of protein skimmers, deep sand beds, and macroalgae harvesting

from refugium tanks, the minor amount of nitrate produced

from one tiny sponge filter should be undetectable in an otherwise

healthy display. If some aspect of husbandry is already lacking,

this added nitrate is certainly not going to help, but the

sponge filter can hardly be blamed.

If the tank does not have a sump, a power filter that comes

with a biowheel can work quite well. Or, some power filters

are available that have large media baskets and durable foam

blocks for a combination mechanical and biological filter.

If these sponges are doubled up and fill the media basket,

a very effective biological filter can be easily established.

Again, whatever method is chosen, it should be operating on

the main display tank so that it maintains a colony of beneficial

bacteria. This way it is ready to be used at a moment's notice.

One never knows when that "cherry" piece of coral

is going to show up at the local fish store, or when that

beautiful fish you have been searching for suddenly becomes

available. Follow the Boy Scouts' motto and be prepared.

By maintaining the biological filter in the main display,

the quarantine tank can be stored until it is needed. This

solves several problems. First, there won't be a second tank

taking up valuable floor space in the house. Second, a proper

quarantine tank is necessarily going to be unattractive. It

should be bare-bottomed and decorated only with inert materials

such as short sections of PVC pipe or fittings. Leave out

the sand, live rock, or anything else that is porous or that

could react with potentially required medications. Such a

tank is certainly not something one would want to show off

during a dinner party, so pack it up when it is not in use.

Third, storing the tank prevents the aquarist from the temptation

of slowly converting it into a second, smaller display or

a frag propagation system or a larval fish grow-out tank or

a phytoplankton culture station or a refugium (or whatever).

Resist these urges and keep the quarantine tank out of sight

when not in use.

Some old "salty dogs" used to recommend keeping

a damsel or similarly tough fish in the quarantine tank to

keep the biological filter active. In this way the quarantine

tank can be left up and running at all times. I really cannot

think of a worse place to add a new, possibly sick, but definitely

weakened acquisition. Damsels are extremely territorial, and

in no time this fish would claim the entire quarantine tank

as its, and its alone, home. Imagine taking one of those accountant

types from Enron and throwing him into a jail cell with someone

like Mike Tyson. It wouldn't be pretty. If you really want

to keep the quarantine tank up and running, I would instead

encourage dosing the tank with bottled pure ammonia or ammonium

chloride, or simply feeding the bare tank, instead of using

a fish. Numerous places online and in print discuss inorganic

cycling of aquariums. Martin Moe's "The Marine Aquarium

Reference: Systems and Invertebrates" discusses this

method of establishing a biological filter, and I am sure

online resources could be found with a quick search using

the keywords, "inorganic aquarium cycling." But,

I know if I had a spare aquarium running empty, it would be

only a matter of weeks before I was utilizing it for a coral

fragment grow-out. That is why I keep the tank packed away

when not in use and the sponge filter operating in the sump

of my display. Maintaining other live animals in the quarantine

tank severely limits one's choices when it comes to treating

sick fish, to the point that it is no better than having the

sick fish in the main display.

In addition to biological filtration, some other form of

circulation to aid in water movement and gas exchange will

be needed. A simple powerhead will work well for this purpose

in a small tank; several would be needed in larger quarantine

systems. Just be sure that its intake is properly screened

to avoid sucking up and damaging or killing your newest purchase.

Sometimes just a regular bioball placed over the intake will

work, or even a simple sponge. Alternatively, special add-on

devices can be purchased to keep errant animals away from

the suction.

Lighting:

No aspect of aquarium

keeping is more likely to elicit strong opinions or spark

a fight than a discussion on lighting. For that reason, I

will try to keep my comments simple. First, it must be kept

in mind what is the intention of quarantining photosynthetic

plants and animals. The intent is to monitor them for pests

and pathogens and to give them some time to acclimate from

the stress of transportation. At this point it is not necessary

to maximize their growth, nor is it necessarily time to bring

out their best colors. That can all wait until they have been

safely moved to the main display. In the meantime, meeting

their basic requirements for energy is all that is required.

To that end, thousands of dollars in high intensity lighting

is an un-necessary investment. On the contrary, by selecting

a shallow aquarium to serve as a quarantine tank, rather modest

lighting can be provided and still maintain the health of

your newest, allegedly super-rare, spectacularly colored Acropora

sp. Additionally, somewhat subdued lighting is appropriate

in many instances for freshly imported photosynthetic livestock

(Borneman, 2001 and Calfo, 2001). Having suffered through

the rigors of importation, high intensity lighting can be

more stressful than a relatively lower light environment as

long as the total energy demands of the specimen are met.

I encourage the reader to browse the Internet looking for

some of the astonishing things people are doing with their

nano-reef tanks. Very High Output (VHO), power compact (PC)

and Normal Output (NO) lamps can be quite effective on small,

shallow aquaria. While these technologies may not generate

the maximum growth or coloration, they are cost effective

and are adequate to keep most anything alive during the quarantine

period. And, given a proper acclimation to the main display

tank's lighting, bleaching or light shock because of the lower

intensity light on the quarantine vessel should not be encountered.

Feeding:

This is another critical

aspect of quarantine. If we are talking about fishes, then

a competition-free environment such as a quarantine tank is

the perfect place to accustom your newest acquisition to feeding

in captivity. It is also a great place to fatten up an otherwise

healthy, but thin, individual who has not eaten enough while

navigating its way through the chain of custody from the reef

to your home aquarium. And finally, this is a good time to

encourage a finicky eater to take prepared foods. Fishes can

be slowly weaned from live prey items, be they feeder fish,

ghost shrimp, or crayfish consumed by Lionfish, Groupers,

Eels, Triggers, and the like, or live brine and mysid shrimp

for tough to feed Seahorses, Dragonets, Anthias, or

others. During this quarantine period, slowly work frozen

and prepared alternatives into the diet as these fish begin

to associate people approaching the tank with feeding time.

For sessile invertebrates, a good diet while in quarantine

is even more crucial. Over the past few years, the importance

of feeding the animals we collectively call 'corals' has become

better understood. It has finally dawned on us that these

are, in fact, animals and they do need to feed. Of particular

importance when discussing feeding photosynthetic creatures

in quarantine is the reality that they are not likely receiving

light much beyond their compensation point. On the positive

side, though, this energy demand can be compensated for with

food. What is important is that it be the right kind of food.

|

An assortment of foods (from left to right): LiquidLife’s

BioPlankton (phytoplankton), Sally’s frozen Pacifica

plankton, LiquidLife’s CoralPlankton (rotifers),

SweetWater Zooplankton (daphnia), sushi nori (processed

seaweed), American Marine’s Selcon vitamin supplement,

Piscine Energetic’s frozen Mysis shrimp,

Boyd’s Vita-Chem vitamin supplement and Argent’s

freeze-dried Cyclops-Eeze. Photo by Steven Pro.

|

I am going to attempt to sum up in a couple of paragraphs

what is really tens of thousands of words and several articles

on feeding. I am necessarily painting with a rather broad

brush, but this should hopefully be helpful and I would strongly

encourage the reader to further research this topic by following

the linked files in my suggested reading list.

Below is a listing of the food items that I use. Under each

one are the various animals I would attempt to feed each food

while in quarantine. This is not a complete list of every

kind of food or every kind of animal one may try to keep.

It is simply an outline of my experience and general recommendations.

|

Cyclop-Eeze:

SPS corals

Feather dusters

Zoanthids & small colonial anemones

Sweetwater

Zooplankton:

Zoanthids & small

colonial anemones

Large polyp stony corals

Phytoplankton:

Clams

Feather dusters

|

Larger plankton

substitutes such as frozen Pacifica plankton and Mysis

shrimp:

Large polyp stony

corals

Anemones

Sushi Nori/Seaweed

Selects:

Snails

Urchins

Rotifers (live

and prepared formulations):

SPS corals

Feather dusters

|

So, how long do I have to wait?

Ahhh, impatience.

No character trait is more likely to kill aquatic pets than

impatience, although laziness (which is related) comes in

a close second in my book! If the time consuming process of

curing live rock and cycling the aquarium was not enough to

teach patience to the aquarist, a properly run quarantine

will. There is no getting around it. For an effective quarantine,

the new inhabitants must be kept for a minimum of one month.

I feel so strongly about this that I would tell you not to

waste your time if you can't commit to this amount of time.

Time would be better spent learning to catch and remove all

the fish from the main display for when an outbreak of a parasitic

fish disease is encountered. Waiting that comparatively short

period of time can be rewarded with the peace of mind of knowing

that the health and well being of your pets has not been jeopardized.

Given that most of the animals kept in reef aquaria have lifespans

from decades to centuries, a month to help ensure their longevity

is inconsequential. Lidl Leaflet

contains Fresh meat, frozen, baby, pet, and many more!Furthermore, the proposition of holding

an animal for a month will also enforce the notion that a

quarantine tank must be a well-thought and designed simple

system that does not cause more harm than good. Too many quarantine

tanks are makeshift operations with conditions about equivalent

in function to the shipping bag of water in terms of stress

and water quality. By following the practices in this article,

quarantine tanks should accomplish all the functions required

of them.

|

|

Both of these Maroon clownfish appear to be suffering from

Brooklynella infections. Quarantine is

definitely recommended for fish in this condition. Photos

by Steven Pro.

Note that the one month minimum period is for a trouble free

quarantine. If the tank has been treated with medications

at any time, the countdown does not start until after the

treatment is finished and the animals are in perfect health.

Realistically, that means some specimens are going to spend

two or more months in quarantine due to the time it takes

to complete a course of the medication or the treatment protocol.

Again, I can't caution aquarists enough. There are no shortcuts

here. Anyone trying to dissuade you is probably just trying

to convince you (and himself) that what they have been doing

for years works fine. Don't be pulled to the dark side. The

lure of simply tossing new fish and corals into one's tank

is attractive, but the Fish Disease Forum is littered with

individuals who bought into that mentality. It simply doesn't

work in the long run. Eventually, the pets you bought and

cared for will end up paying the price.

Prophylactic Treatment:

I occasionally employ

preventative treatment even when an infection may not have

been noticed and I would recommend others do the same. The

reason for this is some fish are routinely plagued by certain

diseases. Many hobbyists miss the signs, or, even if they

see initial signs, they often misdiagnose the malady and use

the wrong treatment. Or, by the time they realize something

is wrong and get the right medication, the fish is too sick

to be saved. Because of that, I propose certain blanket treatment

protocols for some fish. For instance, any surgeonfish/tangs

that I import go through a hyposalinity treatment because

of their propensity to be infected with Marine Ich/Cryptocaryon

irritans. Also, I give all wild-caught clownfish a formalin

bath in case they harbor Brooklynella, a common condition

called "clownfish disease." I also recommend adding

garlic to the food of all quarantined fish as a general immune

system stimulant (Colorni, et al. 1998) and as a de-worming

agent (Fairfield, 1996 and Jedlicki, pers. comm.).

|

A well-stocked and organized medicine chest will go a long

way in helping aquarists treat a

quarantined fish should the need arise. Photo by Steven Pro

of Kelly Jedlicki’s fish medicine chest.

Unlike fish prophylaxis, I don't recommend any preventative

treatment for the invertebrates I purchase. I don't freshwater

dip, iodine dip, or use any sort of commercial bath on any

of my corals. I don't believe we hobbyists understand nor

can we properly identify most coral pathogens or pests, so

I use only close, careful observation over time during the

quarantine of corals. If something can later be identified,

such as pest flatworms, Acropora copepods, or any other pests,

it is far better to deal with it in the quarantine tank where

there is no possibility of spreading it to other specimens

or of collateral damage to beneficial fauna in the display

from the treatment.

Conclusion:

For those who merely

skimmed through the previous 6,000 plus words, let me review

some of the highlights:

-

Quarantine everything! Fish, corals, clams, anemones,

live rock, live sand, mobile invertebrates, and everything

else that is wet. When in doubt, quarantine!

-

A properly run quarantine tank is the best possible way

to ensure the safety and well being of all your aquatic

pets.

-

A competition free environment is the best place to allow

fish and corals time to recover after enduring the stress

and damage from shipping.

-

There are a staggering number of potential pests, predators,

and pathogens that we want to avoid introducing to the

display. And, to make matters worse, not all of them are

readily apparent upon first purchase/inspection.

-

If the tank does become infected, it cannot be assured

that any alleged 'reef-safe' medication is not harming

some inconspicuous, but important, part of the overall

ecosystem.

-

Completely eradicating an introduced problem is always

more difficult and more costly than keeping said problem

out in the first place.

-

A quarantine setup can be extremely simple and affordable,

yet effective, with some forethought and planning.

-

Having a fully functional and cycled biological filter

is key to a successful quarantine period.

-

The quarantine tank's lighting used when housing photosynthetic

creatures need not be very expensive nor as high intensity

as the main display. The animals merely need to be kept

alive. Maximizing coloration or growth at this point is

un-necessary.

-

Any deficiency in lighting can be balanced by feeding.

-

Use prophylactic treatment sparingly. Don't treat anything

and everything, but be aware if the particular species

is known for certain ailments and act accordingly.

-

A proper quarantine period is at least one month long

if everything goes perfectly. If a specimen refuses to

feed, needs to be treated for a disease, or just doesn't

behave appropriately for its species, the countdown to

introduction to the display should not begin.

-

Some specimens are going to be in quarantine for two

months, or perhaps longer, because they need to be treated

and the treatment protocol lasts a month.

-

And finally, if you can't commit to these practices,

don't waste your time because you will eventually run

into trouble and want to blame it on quarantine as a practice

instead of your incorrect application of the technique.

Hopefully, I have convinced the reader what a smart and

safe idea a proper quarantine setup is. Actually, I really

hope that I have scared aquarists not using quarantine, because

the very real fear of what can happen may prompt the use of

a quarantine setup. If not, I wish you the best of luck because

you are going to need it. As I said, those of us who have

the experience of years know the repercussions of not using

quarantine all too well.

|