|

Ornamental Crustaceans

While the main focus of most marine aquariums is either fish or cnidarians (anemones, corals, soft corals, zoanthids, etc.), many aquarists include ornamental crustaceans to provide variety and subtle focus points. Crustaceans are also commonly found in smaller aquariums as either an alternative to fish or in single-species tanks. These crustaceans can vary from spiny lobsters (family Palinuridae) and dwarf reef lobsters (Enoplametopus spp.) to much smaller species such as porcelain crabs (Neopetrolisthes spp.) or anemone shrimp (Periclimenes spp.). Many species are brilliantly colored while others are quite cryptic; some can be part of interesting symbiotic partnerships while others are free roaming and can provide interesting behavioral spectacles on their own. While many crustaceans are attractive and appear to make ideal additions to mixed reef aquaria, most are carnivorous predators and many can be a risk to other inhabitants in the aquarium.

Most ornamental crustaceans belong to the order Decapoda, with the exception of the stomatopods which are considered to be both dangerous pests and attractive aquarium specimens. Most crustaceans are nocturnal and, therefore, in the home aquarium they often are very secretive and may rarely be seen. For this reason, species that have a symbiotic relationship with sedentary partners, such as corals or anemones, are often good choices, especially in larger aquariums. However, several species of ornamental crustaceans do, in time, become confident in their surroundings and, even in large aquaria, become quite active to the point of climbing high in the tank at feeding time to compete with more active tankmates, especially fish.

|

Phylogeny of the ornamental crustaceans discussed in this article. |

Order: Stomatopoda

Stomatopods differ from decapods due to the specialized appendages the former use for hunting, as well as their lack of fused body segments. They have eight pairs of thoracic appendages, known as thoracopods. Aquarists often divide Stomatopods into two groups, the “smashers” and “spearers,” by the type of hunting appendages they possess. While species in these genera are often considered to be pests, many species are kept by aquarists, often in single-species aquaria, as ornamental species. While the “spearers” usually pose more of a threat to fish, the “smashers,” which are more often found in aquaria, can be problematic for other tank inhabitants such as molluscs, bristleworms and other crustaceans. The appendages used by mantis shrimp are very similar to those of the preying mantis, giving rise to their common name. These appendages are raptorial limbs which are modified second thoracopods that are used in hunting, and are known by aquarists, as well as divers and researchers, for their immense striking force. “Spearers” possess long, barbed spear-like appendages they use to feed on soft-bodied prey such as fish; whereas “smashers” have a large club-shaped appendage, as well as a secondary spear they mostly use to crack the shells of prey such as molluscs and crustaceans. The force of these appendages, which can reach speeds of around 23m/s, causes cavitation and a subsequent shock wave from the collapsing bubbles. This shock wave can be almost as harmful to prey as the blow itself, often causing death or severely stunning their prey and enabling a second strike.

|

|

The size and brilliant colors of the peacock mantis shrimp, Odontodactylus scyllarus, make it a popular addition to small single-species aquaria. Photo courtesy of Roberto Sozzani. |

Odontodactylidae/Gonodactylidae (Mantis shrimp)

Both these families of mantis shrimp belong to the “smashers” group and include most species kept by aquarists in single-species aquaria. The gonodactylid family also includes most species found by aquarists hiding in live rock, often causing unnecessary concern for aquarists. In a small aquarium on their own, these shrimp can be very fascinating creatures with brilliant colors and interesting behavior. Species such as the peacock mantis, Odontodactylus scyllarus, can grow quite large (up to around 8”) and can be bold hunters, making them ideal candidates for single-species aquaria. While most stomatopods pose little threat to fish in an aquarium, larger species present a significant risk and smaller species can be a problem if other prey items are not available. If a clicking noise is heard from an aquarium, it often is either a mantis shrimp or a pistol shrimp. If it is a mantis shrimp it is almost certainly a “smasher,” and therefore little threat to fish.

Order: Decapoda

This order is distinguished from other crustacean groups by both their structure and reproductive behavior. These crustaceans possess five pairs of pereiopods (walking legs) which give them their name and, in some groups, one pair, usually the first, is modified into clawed arms known as chelipeds. Female decapod crustaceans carry their eggs within their pleopods and once the eggs have reached full-term development they are released. The female releases her larvae into open water by flicking her abdomen, and they become plankton until they are old enough to settle onto the reef. Some species are easily bred in captivity and these tank-raised individuals are sometimes offered to aquarists. The planktonic larval stage in most species, however, is too long for them to currently be bred in captivity.

|

Basic anatomy of a decapod crustacean. In some groups such as brachyurans, the pleon is folded beneath the carapace. |

Cephalothorax – The anterior segments that include the cephalus (head) and thorax.

Pleon – The posterior segments that are also known as the abdomen or “tail.”

Pereipods – Thoracic appendages, used mainly for walking. Some pereiopods are modified as claws, known as chelipeds.

Pleopods – Abdominal appendages whose primary function is locomotion, giving them their name “swimmerets;” they are also used by females of most species for egg brooding. |

Infraorder: Stenopididea

This small group is comprised of only two families and six genera, similar in appearance to both prawns (decapod subfamily: Dendrobranchiata) and shrimp (infraorder: Caridea). They are easily distinguished, though, by their third pereiopod, which is modified as a cheliped, instead of the first as in many other crustacean groups.

Stenopidae (Coral shrimp)

This family is represented in the aquarium trade largely by a single species, Stenopus hispidus, but several species from within the same genus are commonly kept by aquarists. These “shrimp” are carnivorous and feed largely on polychaete worms and small gastropods, which means that in an aquarium they may be a risk to populations of bristleworms, tubeworms and small snails such as Nerites or Cerith spp. The diet of many stenopids also often includes algae and, like many crustaceans, these creatures are also opportunistic scavengers. It must also be noted that these shrimp have the ability to kill and eat small fish such as gobies and blennies.

|

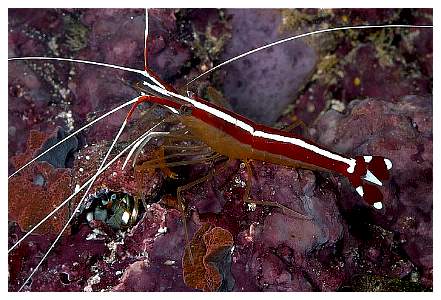

Stenopus tenuirostris. Photo courtesy of John Clipperton. |

The shrimp in the genus Stenopus are known as coral banded shrimp due to their white and orange/red banded pattern, best shown in S. hispidus. They are also known as boxing shrimp due to their long chelipeds and defensive behavior. Variations of the banded pattern are found in many species such as the smaller S. tenuirostris and S. scutellatus, which have blue and gold carapaces, respectively, although both species still possess white and orange bands along the remainder of their body, including their chelipeds. Species such as the rare S. pyrsonotus demonstrate a variation from this banded pattern, but are much less common in the aquarium trade. Stenopus spp. do not live peacefully with conspecifics of the same sex, and because it can be difficult to sex these animals, it is recommended they be kept on their own unless they can be purchased as a mated pair or they are being added to a very large aquarium.

|

|

Stenopus hispidus, a common shrimp that's well-known to most marine aquarists. Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild. |

The second genus within the family is Odontozona,which is a group of deep water shrimp not often found in the aquarium trade and not kept as ornamental shrimp.

Infraorder: Caridea

While many groups of crustaceans are referred to as shrimp, including Mysis shrimp, mantis shrimp and shrimp (or prawns) used as seafood, the true shrimp belong to the infraorder Caridea. Some groups' first pair of pereiopods are modified as chelipeds, while in other groups this has not occurred. Many species of caridean shrimp have symbiotic relationships with other organisms, including corals, anemones, molluscs and even fishes. In some cases this is a permanent relationship such as a Periclimenes brevicarpalis living within the tentacles of a Stichodactyla mertensii, while some such relationships are short-term such as Lysmata amboinensis removing parasites from a fish as it moves through a cleaning station. Many of these symbiotic relationships occur in aquariums despite their lack of necessity, given the absence of potential predators and, in the case of cleaner shrimp, even without obvious parasites and the lack of cleaning stations, they often climb aboard large fish such as surgeonfishes and angelfishes.

Rhynchocinetidae (Hingebeak shrimp)

Known by many names such as candy, camel, dancing and hingebeak shrimp, these small shrimp are colorful and peaceful animals that are popular and common in the aquarium trade. While they are no threat to fish or other crustaceans, these shrimp usually feed on the tissue of corals, zoanthids, corallimorphs and soft corals. These shrimp, therefore, can be a useful tool in the eradication of pest anemones such as Aiptasia spp. and Anemonia majano. Unlike many other shrimp, which fight with conspecifics, rhynchocinetids can be kept in small or large groups with few or no problems, thereby making them ideal for either small or large aquaria. These shrimp possess small chelipeds that are used mainly for territorial battles and for feeding purposes.

Hippolytidae (Cleaner/broken back shrimp)

This is a family of shrimp containing several genera that are popular in the aquarium trade and, in general, are easy to keep, peaceful species. Popular genera in this family include Lysmata, Saron and Thor.

|

Lysmata wurdemanni, known to aquarists as a weapon against the pest anemone Aiptasia.

Photo courtesy of John Susbilla. |

The Lysmata spp. are sought after both for ornamental and functional purposes, with species such as L. debelius and L. amboinensis being very attractive and interactive shrimp, while species such as L. wurdemanni are considered an effective weapon against the nuisance anemone Aiptasia. The cleaner shrimp such as L. amboinensis and L. debelius interact with fish in the aquarium as they would in the wild, climbing onto cooperative fish and removing any parasites that are present. While Lysmata spp. do not possess the chela that many crustaceans use to defend themselves, they are quite bold and happily roam the tank throughout the day once they are comfortable in their surroundings. This is especially true if they are kept in pairs, which is easy to do because all species are hermaphrodites. Lysmata wurdemanni are one of the shrimp species currently being bred in aquaria and are often commonly available to aquarists. As with all captive-bred species, they are a more sustainable, and often a more robust, option than wild caught specimens.

|

|

One of the more popular ornamental shrimp, Lysmata amboinensis, is known for providing a "cleaning" function, riding tankmates of parasites. Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild. |

Other popular ornamental species in this family include Saron marmoratus (marble shrimp) and Thor amboinensis (sexy shrimp), which are both common in the trade and are quite hardy tank inhabitants. Unlike other species within the family, Saron marmoratus is a destructive and aggressive shrimp that does not live peacefully with cnidarians or other crustaceans. It is not a species that lives in symbiosis with other animals, nor does it have any traits that make it advantageous to the aquarium. For these reasons, these shrimp are best kept in fish-only aquariums with no other ornamental crustaceans. Thor amboinensis, however, is a small (>1”), peaceful species that lives in a symbiotic relationship with anemones and corals such as Heliofungia actiniformis.

|

A very small and often inconspicuous shrimp, Thor amboinensis is probably best suited to small, peaceful aquaria. Photo courtesy of Kayla Swart. |

This family also contains some small colorful shrimp such as Labbeus spp., which are found primarily in temperate regions and are, therefore, of little interest to the aquarium industry. For the few aquarists who keep temperate aquariums, however, these shrimp make excellent additions as they are similar to Periclimenes spp. in both color and size.

|

A very beautiful aquarium specimen, Lysmata debelius has an intense red coloration that catches the interest of aquarists and non-aquarists alike. |

Palaemonidae

|

Periclimenes brevicarpalis amongst the branches of a soft coral. Photo courtesy of Robie Sayan. |

This is a very large family of shrimp that includes many genera of freshwater prawns and marine shrimp, as well as a couple of ornamental shrimp genera such as Periclimenes and Urocaridella. Species from this family are often used by aquarists as “feeder shrimp” for other predatory creatures such as fish, cephalopods or other crustaceans; however, many aquarists recognize this family's commensal species, which live in association with anemones, nudibranchs, corals and other invertebrates. Aquarists may occasionally find species such as Paranchistus ornatus or Anchistus spp. living within the mantle cavity of Tridacna spp. clams.

Periclimenes spp. are often available in combination with anemones and are occasionally sold with an anemone unbeknownst to the retailer. One of the most common species available, P. imperator, can be found in association with various organisms including the Spanish dancer nudibranch, Hexabranchus sanguineus, seastars, sea cucumbers and other nudibranch species. These small shrimp are often difficult to keep long-term for a variety of reasons including predation, competition and lack of a suitable food source. Some species feed on slime produced by their host, while others are planktivores and some others are a combination of these. Commonly available in the trade as pairs, these shrimp are quite peaceful and often share hosts with other species such as anemonefishes.

Alpheidae (Pistol/snapping shrimp)

The Alpheus genus is the group with the main representation within the aquarium trade, although there are several other genera within the family including Synalpheus, Pterocaris and Yagerocaris. Alpheus are an unusual group of shrimp which are known as snapping shrimp due to the enlargement of one of their chela, which can create a loud snapping or clicking sound used to fend off potential predators or competitors. This clicking sound is a result of their large chela snapping rapidly, which caues a shock wave similar to that of mantis shrimp. An interesting fact about their enlarged chela is that if it’s removed by a predator or competitor, the shrimp can reverse its claws such that the smaller claw can grow and when the removed limb regrows, the new claw becomes the smaller of the two.

|

A brightly colored Alpheus sp. shrimp emerging from its burrow. Photo courtesy of Bill Chamberlain. |

Alpheus spp. are known well by both divers and aquarists for their symbiotic relationship with gobies such as Amblyeleotris spp., Cryptocentrus spp. and Mahidolia spp. These shrimp are almost totally blind, and this relationship benefits both parties by providing the shrimp with a pair of eyes to watch for predators; in return, the shrimp builds a burrow for both the shrimp and goby to live in. As the shrimp builds the burrow it keeps a single antenna on the goby and if the goby moves suddenly, the shrimp retreats into the hole with the goby following close behind.

Gnathophyllidae (Harlequin shrimp)

While this family contains several genera, the only genus of interest to the aquarium trade is the genus Hymenocera. The Hymenocera spp. are some of the most attractive shrimp available, but also are some of the most difficult to keep due to their unique diet. These shrimp require the ambulacral system of echinoderms, such as Asteroids (sea stars) and Echinoids (urchins), as part of their diet. These shrimp are quite small but they have the ability to move much larger seastars into caves where they turn them over and feed on their tube feet. In the aquarium it may be difficult to obtain a consistent supply of seastars to support the feeding of these shrimp, and it is essential to ensure that their dietary requirements can be provided prior to their purchase. It is possible to obtain seastars that reproduce by fission (various Asterina sp. stars, for example), and these are often considered to be pests in the reef aquarium. It would be ideal to house these in a separate aquarium where they are allowed to reproduce to numbers that will make regular feedings sustainable.

|

|

Hymenocera picta, one of the most beautiful crustaceans available to aquarists, can be distinguished from its cousin H. elegans by the color of its spot. Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild. |

Infraorder: Anomura

This group is divided into four superfamilies, two of which are of interest to aquarists. These are the galatheoideans, which include the porcelain crabs (Porcellanidae) and squat lobsters (Galatheidae and Chirostylidae), and the paguroideans, which include several families of hermit crabs, of which only a few are of interest to the aquarium trade such as the scarlet hermit crab, Paguristes cadenati. While hermit crabs are sometimes added to an aquarium as part of a “clean-up crew” and squat lobsters are not uncommon additions with live rock or corals, neither will be discussed in any detail here as they are not really considered to be ornamental.

Porcellanidae (Porcelain crabs)

|

At first glance porcelain crabs can be distinguished from true crabs by the presence of antennae. Photo courtesy of Kayla Swart. |

This family would be best known to aquarists by the species within the genus Neopetrolisthes, but it also includes many other genera, several of which are found in the aquarium trade, such as Petrolisthes and Porcellanella. Porcelain crabs are distinguished from true crabs (Brachyura) by their lack of fusion between their abdomen and thorax, which allows these crabs to use their abdomen to propel themselves away from potential predators. They also have a pair of antennae which distinguish them from true crabs, and they appear to have only three pairs of walking legs, but the fourth pair (the fifth pair of pereiopods) is actually tucked beneath the abdomen. Porcelain crabs have enlarged chelae but feed on plankton that they catch using specialized mouthparts called setae. Setae are hair-like structures that are used to filter plankton and other particulate matter from the water column, which are then scraped into their mouth. Like most crustaceans, however, porcelain crabs are opportunistic scavengers and also feed on detritus; in aquaria they accept most foods such as fish flakes, pellets or meaty foods such as shrimp or pieces of fish. The chelae in these species are used only for defense and during territorial challenges.

|

|

A porcelain crab, Neopetrolisthes maculatus, seen here living amongst the tentacles of a Heteractis crispa anemone. Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild. |

Neopetrolisthes spp. are most often found in association with anemones, especially those from the genus Stichodactyla, and usually share their host with anemonefish; while other species in the family are found in association with various corals and soft corals. Other genera within the family are not often found living in association with symbiotic partners. While porcelain crabs are not difficult to keep, those that associate with anemones should be avoided by inexperienced aquarists due to the difficulty in keeping many host anemones.

|

A porcelain crab, Neopetrolisthes ohshimai; the fifth pair of pereiopods can be seen tucked beneath the first pleon segment. |

Infraorder: Astacidea

This group of crustaceans is well-known to both the aquarium and seafood industries, containing marine and freshwater species used in both industries. In the seafood industry these include the large-clawed marine lobsters (superfamily Nephropoidea), as well as freshwater crayfish (superfamily Astacoidea). For the aquarium trade these include the dwarf reef lobsters (superfamily Enoplometopoidea) and the southern hemisphere freshwater crayfish (superfamily Parastacidae). All species within this family have enlarged chelae used both for defense and as an effective weapon for predation.

|

Enoplometopus spp. have powerful claws making them unsuitable for most aquaria.

Photos courtesy of John Clipperton. |

Enoplometopidae (Dwarf reef lobsters)

This family of dwarf lobsters contains a single genus, Enoplometopus, which now also includes the species from the former genus Hoplometopus. These small lobsters are generally more colourful than their larger relatives and are distinguished from larger lobsters by their second and third pereiopods not being fully chelate. Also, unlike their larger relatives, dwarf lobsters can be distinguished by the presence of sensory hairs over their entire exoskeleton. Lobsters are generally secretive, nocturnal creatures and are, therefore, better suited to smaller aquaria where rockwork can be arranged so that it is possible to view inside caves that may be used as hiding places. Like many other predatory crustacean species, these animals can be a threat to both fish and other small invertebrates, including other ornamental crustaceans. Dwarf lobsters are opportunistic scavengers and in the aquarium they readily accept most foods such as dried, fresh or frozen fish foods.

|

|

Enoplometopus occidentalis in the home aquarium. |

Infraorder: Palinura (Achelata)

This is a small group of crustaceans that includes only two families, Palinuridae (spiny lobsters) and Scyllaridae (slipper lobsters), which differ from true lobsters by their lack of claws (giving them the alternate name Achelata), development of enlarged antennae and a larval form called a phyllosoma. While scyllarids are occasionally offered in the aquarium trade, their main commercial use is in the seafood industry, and aquarists are usually more interested in keeping palinurids.

Palinuridae (spiny lobsters)

These larger lobsters, known as spiny lobsters or crayfish, are mainly of interest to the seafood industry, especially the species from the genus Jasus. Of interest to the aquarium trade, however, are the Panulirus spp., which are generally much brighter in color than the family's other genera. While not entirely common in the aquarium trade, small specimens of a few species such as Panulirus versicolor and P. penicillatus are sometimes available to aquarists, but are often sold to uninformed buyers. These brilliantly colored animals can reach over 16”, and often up to 20”, in length, and can be quite destructive in the home aquarium. Spiny lobsters are carnivorous scavengers but also feed on beneficial tank inhabitants such as gastropods and polychaetes, as well as smaller crustaceans and, potentially, small fish. This group of crustaceans is probably best suited to large fish-only aquariums due to their opportunistic and destructive feeding behaviors. Palinurids are also known to burrow and, given their size, they may move enough substrate to cause rockwork to collapse, causing a number of problems including the potential death of the lobster or other tank inhabitants.

Infraorder: Brachyura

|

A sally lightfoot crab, Percnon gibbesi, makes a useful addition to aquaria for the combat of nuisance algae and poses less risk than many crabs. Photo courtesy of Robie Sayan. |

Brachyura is by far the largest group of decapods, with around 70 families, roughly the same number as the total number of families from all other infraorders. This group is known as the “true” crabs and is distinguished from other crab groups by having a very short abdomen that is permanently held beneath the carapace. All true crabs possess chelipeds and, in some species, the chela can be quite large, making them very difficult to handle. This group includes many species of crabs commonly kept by aquarists such as the sally lightfoot crabs (Grapsus grapsus and Percnon gibbesi) and arrow crabs (Stenorhynchus seticornis), but these crabs are usually added to aquariums for functional, rather than ornamental, purposes and can be a risk to their tankmates. As a general rule, brachyurans are probably best kept out of mixed reef aquaria as even many of the most peaceful species can become problematic due to their opportunistic nature. Many species within this group are found in aquaria after being introduced on live rock. While many may never cause problems, a large number of aquarists are well aware of the hassle involved in removing problematic crabs.

Xanthidae

The family Xanthidae is a large family of crabs containing many genera found in marine aquaria, but very few that are kept as ornamental species. One of the few genera in this family that is sought after by aquarists is Lybia spp., or pom pom crabs, which are known for the fact they carry a pair of small white anemones on their chela. While many species of xanthid crabs are kept by aquarists, most pose a threat to fish and other aquarium inhabitants, so most that are found on live rock are unwanted by aquarists. When the crab is ready to moult, it leaves the anemones attached to the shell that it sheds and then removes them from the discarded moult once completed. While these crabs are not especially difficult to keep, they are easy targets for predators and are, therefore, very secretive, making them more suited to smaller aquaria.

|

The pom pom crab, Lybia tesselata, is one of the few crab species that poses almost no threat to fellow tankmates. Photos courtesy of John Clipperton. |

This family also includes a group of crabs known to aquarists as “acro crabs” such as Xanthasia spp. Aquarists continue to debate whether they are detrimental or beneficial. Their symbiotic relationship with corals, usually those from the families Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae, gives the corals a defense against predators because these crabs attack predatory seastars such as Acanthaster planci and fish such as butterflyfishes. The crab also feeds on mucous produced by the coral and, in captivity, some evidence suggests that the crab is detrimental to the coral because the tissue around where the crab lives often starts to recede, causing necrosis that spreads across the coral. Similar crabs from the family Trapeziidae live in the same corals and cause similar problems for aquarists.

|

Although these symbiotic crabs are considered by many aquarists to be pests, others are intrigued by their unusual behavior. Photos courtesy of A.J. Mickelson (left), Robie Sayan (center) & Mitchell Brown (right). |

Considerations for Their Care

While care must be taken with the compatibility of crustaceans with other aquarium inhabitants, many of these fascinating creatures make excellent additions to both large reef aquaria and smaller nano reefs and single-species aquaria. While it should be obvious to most aquarists that it is best to avoid mixing ornamental crustaceans with large predators such as scorpionfishes (Scorpaenidae), groupers (Serranidae) and triggerfishes (Ballistidae), care should be taken when mixing crustaceans even with smaller “reef safe” fish such as wrasses (Labridae), dottybacks (Pseudochromidae) and hawkfishes (Cirrhitidae) because they are often specialized crustacean predators. It must also be noted that when adding species that live in symbiotic partnerships with anemones, such as Periclimenes shrimp or Neopetrolisthes spp., it may or may not be possible to keep them with anemonefish. Usually the fish and crustaceans live harmoniously, but they must be carefully watched when first introduced as some initial conflict often arises.

The diet of the individual species must always be considered before adding them to the aquarium. All crustaceans routinely shed their exoskeleton as they grow, and it is recommended that the discarded moult be left in the aquarium, as the animal will feed on it because it contains necessary elements such as iodine that aid in strengthening their new exoskeleton. Feeding these animals a diet that includes brine shrimp or Mysis shrimp also helps them to acquire the necessary elements for healthy growth and repair. Many aquarists believe that iodine dosing is required for the healthy growth and replacement of exoskeletons in crustaceans, but this is not true; sufficient nutrients should be attained through correct diet alone.

Care should also be taken when adding different ornamental crustaceans to the same aquarium. All crustaceans are either carnivores or omnivores, and most feed on fellow crustaceans if the opportunity arises, even to the point of being cannibalistic. Even if two species are seen together in an aquarium, this does not mean that the combination will always work, especially if it is attempted in a smaller aquarium. It is not uncommon, for example, for aquarists to keep Lysmata amboinensis with Stenopus hispidus, but in some cases the latter can become aggressive and kill the smaller, less aggressive shrimp. In some cases, such as with some stenopids, other crustaceans are a preferred prey item, and they should not be kept together under any circumstances.

Many groups of crustaceans not discussed in this article may be considered ornamental crustaceans, including the previously mentioned Trapeziid crabs, as well as horseshoe crabs (Limulus spp.) and decorator crabs (Cyclocoeloma tuberculata). Even barnacles are occasionally added for ornamental purposes, but they are either uncommon in the aquarium trade or are added to the aquarium inadvertently with other additions, such as corals or live rock.

References

Calfo, A., Fenner, B. 2003. Reef Invertebrates: An Essential Guide to Selection, Care and Compatibility. Reading Trees and Wet Web Media Publications.

Australian Coral Reef Society. 1994. A Coral Reef Handbook. Surrey Beatty & Sons.

If you have any questions

about this article, please visit my author forum

on Reef Central.

|