|

Spawning

and Rearing the Yellow Watchman Goby

(Cryptocentrus cinctus)

When writing an article on breeding

a particular type of fish, authors typically follow a format

that starts with an introduction of some sort that discusses

the fish in the wild, its suitability for the aquarium hobby

and its relationship with other fish, corals or invertebrates.

Well, I have never studied this fish in the wild. Brood stock

pairs are kept in bare tanks by themselves. All I have done

is pair and spawn these fish and raised their babies, so that

is all I am going to write about here. I hope this doesn't

disappoint anyone.

After a few years of raising several types of clownfish,

I wanted to move on to a new challenge. I knew that at least

one commercial hatchery was raising yellow watchman gobies

(YWG), so I figured that they would be good as a new candidate

to try and raise. I also knew that a friend of ours had a

pair that had just come out of a reef tank that he had recently

taken down. This pair went into a 20-gallon long tank with

a couple of pieces of PVC pipe and a piece of artificial coral

décor that makes a nice cave. It surely is a step down

from the fully-stocked 92-gallon reef tank from which they

came, but they seemed right at home; so much at home, in fact,

that they spawned only 12 days after moving in. This pair

must have already been spawning in their prior residence.

They didn't give us any time at all to do any research. So,

we hit it our efforts hard and heavy, scouring the internet

for information, but ultimately finding nothing more than

mentions that yes, they do indeed spawn in captivity. The

first thing we wanted to know was if the rotifers we use,

Brachonius plicatilis, to raise the clownfish would

work as a first food for these gobies. We even asked this

question of the one hatchery that raises YWGs and they told

us, not in so many words, to take a hike. I suppose that is

understandable, since a lot of time and money go into researching

techniques due to the trials and tribulations of raising fish.

For the first batch we pulled the nest into the hatching

tank early, or so we thought, only three days after it was

laid. The first thing we learned is that they hatch after

only four days of incubation. Boy, these babies sure

look small! They are definitely smaller than newly hatched

A. ocellaris clownfish. So, in went the rotifers that

we use to raise the clownfish; my fingers are crossed. After

a couple of hours of staring at the little dots in the tank

trying to determine if the babies are eating, I felt that

my eyes were in danger of becoming crossed as well. As a side

note, to this day the only reliable method we have found to

tell if the newly hatched fry are eating is if they live past

the first four days. Well, the days went by and there were

fewer and fewer babies in the tank and more and more rotifers.

After four days all that remained were eight gallons of a

nice, dense rotifer culture. The next few spawns progressed

pretty much the same way, but we were now testing the water

quality of the hatchout tank to ensure the babies weren't

being killed by something instead of starving to death. We

couldn't find anything obviously wrong, so we inferred that

the food we were offering them was not small enough. After

about the fifth or so failure my husband used a microscope

to get a good close-up view of what we were dealing with.

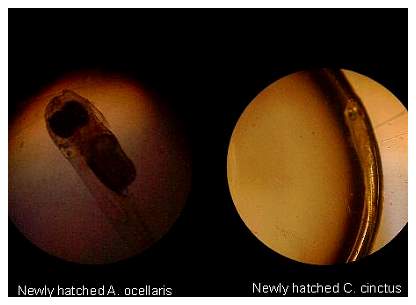

As can be seen in the pictures below, a newly hatched C.

cinctus is about one-fourth the size of a newly hatched

A. ocellaris. So, the quest was on to find a food that

we can use that is smaller than the commonly available rotifers.

|

Both pictures were taken with the same magnification.

Our searches revealed a company that specializes in producing

small live food for larval fish. Here is the intro from their

website that explains what they do:

"TrochoFeed is a cryopreserved starter feed for

larval marine fish. TrochoFeed is the first and only "instant

live feed" for marine larval rearing. It is a suspension

of living trochophore-stage Pacific oyster larvae in seawater,

cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until the moment they're

needed to feed your fish. Trochophores are an ideal first

feed for larval marine fish because they are 50µ,

free-swimming ciliated organisms that are extremely high

in nutritional value."

Only 50 microns and free-swimming… wow, I had found

just what we needed! Or so it seemed, except that a tube of

the stuff that would last four days, at most, costs $75, and

there is a $100 shipping/handling charge with each order,

and they have to be stored in liquid nitrogen until ready

to use. Well, we thought maybe there was something else we

could try; we just didn't have that kind of money to spend

on something that we were not even sure would work. After

looking around some more, I found an aquaculture company in

our area that specializes in producing food clams. I figured

clam trochophores can't be much different from oyster trochophores.

I'm sure that at this point you are asking, "What, exactly,

is a trochophore?" Simply put, it is the initial larval

development stage of a young clam or oyster before it develops

the larval shell, and before it settles out of the plankton.

The people at the aquaculture facility were very helpful,

but their spawning schedule never coincided with that of our

pair of fish. Since my husband works at a lab and had access

to liquid nitrogen, he thought he would attempt to cryonically

preserve a batch of clam trochophores. When the next spawn

came, he gave his DIY cryo-preserved trochophores a try. Unfortunately,

I discovered four days later that it didn't work. I'll spare

the details of his research into methods of cryonically preserving

living organisms, which is a little more involved than just

dunking them into liquid nitrogen. Since my husband couldn't

manage to preserve the clam larvae provided to us, I figured

the alternative was to get some clam broodstock and spawn

them ourselves, to have the larva when I needed them. I simply

followed the instructions in the Plankton Culture Manual1,

and I had some live clam larvae for the newly hatched fry.

Well, that didn't work, either. Much later, we discovered

that it takes weeks for the fry to become large enough to

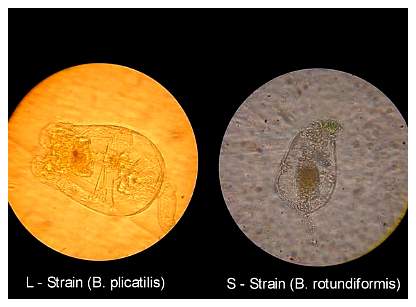

accept the L strain rotifer (B. plicatilis), and considering

that the clam trochophores are free-swimming and at the appropriate

feeding size for only 12 to 18 hours, that equates to a lot

of work just to spawn the clams, not to mention raising the

Yellow Watchman gobies' fry.

After giving up on the clam trochophores, we went in search

of the elusive S (small) strain rotifer (Brachonius rotundaformis).

A lot of information about these rotifers is available on

the internet, but very few vendors actually stock them. One

aquaculture facility in Canada claimed to have them in stock

but "not enough to spare." We then contacted the

Oceanic Institute in Hawaii. It had some really helpful people,

who sent us some of what they had of their S-strain rotifers.

The problem we ran into, however, is that there is no such

thing as overnight delivery from Hawaii to the east

coast of the U.S., and this was in the heat of summer, so

the cultures we got from them did not survive the transport.

I have to say one of the best things about being on Reef

Central is the relationships you build with all sorts of people.

We finally received a hot tip from a Reef Central member as

to where we could track down a source of S-rotifers. I contacted

this source and very soon thereafter had in my hands a vial

of B. rotundaformis cysts. We followed the normal protocol

of hatching the cysts and starting a culture, and this went

flawlessly. From the information we found in earlier internet

searches, it was said that the S strain does best at high

temperatures, around 95°F.

Finally, after about a year and 13 spawns from our pair,

we got it right. We offered them the S strain rotifers and

after four days it didn't appear that we had lost many. We

took pictures of them under the microscope at several points

and their development, which is very difficult to see with

the naked eye, can be clearly seen.

Finding an appropriate first food was the initial hurdle,

but we had a few more to cross. Thankfully, the others were

minor in comparison. Through trial and error, and the loss

of a few batches in the process, we determined the best times

to switch to the next size of food. For us, it seems that

about the 14 day point is the best time to start switching

them over to the L strain rotifers, and it appears that at

about the 28th day they

should be offered newly hatched baby brine shrimp. As with

raising any fish, there will always be some that grow much

faster than the others. But because this fish takes a relatively

long time to develop, this seems especially exaggerated. We

have found that in some batches, some will be fully-metamorphosed,

fully-colored juveniles that are almost big enough to eat

adult brine shrimp while others are still free-swimming and

eating rotifers. And, as you can imagine, there is some predation

of siblings among tankmates when you have this large a difference

in size.

|

A female YWG is seen in the foreground with a male tending

a nest of eggs.

One thing I have omitted so far is pairing the gobies. In

what I have seen of this fish, I believe they are sexually

dichromatic, meaning that the male and female are different

in color. With every pair that I've seen, the male is bright

yellow while the female is grayish, with both having blue

dots along their body. But what makes this confusing is that

I have seen this fish change color in both directions. Does

this mean that they are changing gender as well? I do not

know. After the babies settle out and metamorphose, they are

yellow. Then, as they grow over the next few months, most

of the largest ones will change to the female coloration.

From a few people who we have sold these fish to, we have

reports that some changed back to yellow after they received

them. Despite this confusion over coloration and gender, it

is not difficult to form a breeding pair. I believe the best

and easiest way is to pair one that is larger and gray with

one that is smaller and yellow, though I have also heard from

breeders who have put two yellow ones together and ended up

with a pair. Not only is it fairly easy to pair this fish,

it isn't very hard to get them to spawn. I would suspect that

many people who have two of these fish in a reef tank already

have had spawns and just don't know it. One more interesting

point is that our broodstock male passed away a few months

ago, so we took one of the largest males we had in reserve

(my husband had him in a nano reef in his office) and put

it in with its mother. In just a few short weeks, they spawned.

But now our broodstock female looks like she will be leaving

us soon, as well. She is acting and looking much like our

male did before he passed on. Considering that the original

pair we started with are at this point over 10 years old,

I bet that the problems we are seeing with them are related

to being near the end of their normal life span. The mother/son

pair has not spawned in a couple of months now, but we do

have a female on standby to replace her when she passes. And

then we will be back into raising these fish.

|

Both pictures were taken with the same magnification.

Both pictures were taken with the same magnification.

The L strain rotifer is used in this comparison.

An extremely small portion of a nest shortly before hatching.

A YWG larva on day three.

A YWG larva at day five.

A YWG larva at day seven.

A YWG larva at four weeks.

A YWG at two months. This one is starting to exhibit the female

coloration.

Raising YWG is not as easy as raising clownfish, but it is

not as difficult as some fish such as the pygmy angels. My

heart really goes out to those people who work so hard to

pioneer raising a new fish at what often turns out to be a

financial loss. The problem is that because of the financial

aspect of it, information sharing is almost non-existent.

That is why we have found internet breeding forums to be so

valuable, even if we end up giving more than we receive. So,

it is my hope that this article will help someone and essentially

be what I hoped to find when starting this project.

A sight that makes any fish breeder happy!

Photography by Alan Drehmel.

If you have any questions about this article, please visit

my author forum

on Reef Central.

References:

1. Hoff, F.H., Snell, T.W., Plankton Culture Manual,

Florida Aqua Farms Inc; ISBN: 0966296001; 5th

Rev Edition (July 1999).

|