|

Deep in the Central

and South American jungles are several small monkeys collectively

referred to as the Tamarin Monkeys. They live nearly their

entire lives in trees, minus the ones which are kept as house

pets, obviously. When the majority of biologists speak of

Tamarins, they undoubtedly are speaking of these primates.

When marine biologists speak of Tamarins, however, they are

not concerning themselves with the fur-ball with a whip-like

tail. Instead, they are discussing a genus of marine fish.

What is the connection between the monkeys and these fish?

Nothing more than a coincidence, it seems. The genus Anampses

was more likely given its unusual common name after the Tamarin

Bay located in Mauritius. I will leave the discussion of the

monkeys for another day and instead focus upon the Tamarin

wrasses for the August edition of Fish Tales.

|

|

|

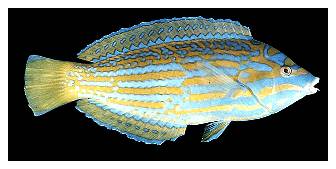

The Elegant wrasse, Anampses elegans, is certainly

more colorful as a male (top) than as a female

(bottom). Juveniles are nearly completely green.

Their limited geographical distribution likely eliminates

any chance of seeing these in home aquariums with any

regularity. Photos courtesy of John Randall.

|

Meet the Family

Labridae is the

second largest marine fish family and contains 60 genera,

one of which is Anampses. Anampses is further

divided into two subgenera: Psuedoanampses and Anampses.

Thirteen species are included in the genus (see below). All

Anampses, must possess set of morphological features

which includes "a single pair of broad, projecting incisiform

teeth at the front of the jaws, scaleless head, smooth preopercular

margin, and complete lateral line" (Randall, 1972). The

subgenera differ in the number of lateral line scales. Psuedoanampses

will have 48-50 scales while Anampses have only 26-27.

One species, A. melanurus, was further divided into

two subspecies. Known only from the Red Sea, A. melanurus

lineatus is colored slightly differently than the wider-ranging

A. melanurus melanurus. As its name suggests, lines

or dashes are present on A. melanurus lineatus, whereas

the marks are present only as spots or dots on A. melanurus

melanurus.

|

Labridae

- Anampses

- Anampses

- caeruleopunctatus

- chrysocephalus

- cuvier

- elegans

- femininus

- lennardi

- lineatus

- melanurus

- meleagrides

- neoguinaicus

- twistii

- viridis

- Pseudoanampses

|

|

Like so many of the Labrids, Anampses has been a confounding

genus for ichthyologists to organize. Most species in the

genus have up to three distinct color variations which at

one time caused ichthyologists to consider that the genus

contained up to 32 species (Randall, 1972). Careful study

and documentation, mostly by observing natural behavior in

the wild, has resulted in the trimmed down list seen above.

The genus was introduced to the scientific community by Quoy

and Gaimard (1824) with the description of Anampses cuvier.

By 1839, seven more species had been assigned to the genus

Anampses. Ruppell (1828) was responsible for naming

A. caeruleopunctatus and then A. diadematus

(Ruppell, 1835). As an example of the confusion that the color

patterns in the genus amy caused, this latter species was

later determined to be a male of previously described A.

caeruleopunctatus (Randall, 1972). Bleeker identified

five additional species during a period of 22 years, but only

two are now recognized as valid: A. twistii and A.

melanurus. Additionally, it was Bleeker (1862) who first

recognized that A. geographicus warranted separate

classification by offering Pseudoanampses as a possible

generic name; however, he still retained the name Anampses

for this particular specimen. This is key, because despite

the overabundance of named species, every author correctly

placed each species into its correct genus - something of

a rarity in ichthyology, considering the confusion that existed

within genus.

|

|

|

The olive green coloration of the juvenile Anampses

geographicus (left) is indicative of the

shallow, often algae covered territory it prefers. At

7 - 8 inches they will become functional males (right).

Photos courtesy of John Randall.

|

Throughout the early- to mid-1900's authors attempted to

align the species into synonymy. Although the vast majority

of these attempts were in error, nine connections proved to

be correct. Ironically, none of the correct synonyms was of

different sexual forms. At this time sexual dimorphism was

not a factor to be considered since it was not understood.

This is because fish species were, and are, described primarily

from preserved specimens, and colors are lost in preservation

as most of the proteins that they are based on are denatured.

Virtually all preserved fishes are white, yellow or grey,

the colors of most tissues in formaldehyde solutions. Finally,

Randall (1958) offered just such a theory when he placed Anampses

pterophthalmus into synonymy with A. geographicus,

which was shortly followed by Whitley (1964) proclaiming,

"due to variations in colour with growth or sex in these

fishes, it is probable that the number of species may be drastically

reduced." And so it was with the release of Randall's

findings (1972).

In the Wild

The vast clear-blue

seas of the tropical Indo-Pacific house all species of Anampses.

Anampses caeruleopunctatus is the most widespread of

all species, and its vast distribution seems to be an anomaly

among members of this genus. Unlike many Red Sea natives,

which rarely have a geographical range outside of the Red

Sea, A. caeruleopunctatus remains plentiful on most

extensive reef systems extending from the Africa's east coast

all the way to Easter Island, although it has yet to be sighted

around the Hawaiian Islands. Instead, its very close cousin,

A. cuvier, is found around the big island. Ironically,

A. cuvier remains endemic to only the Hawaiian Islands,

and thus shares the most limited geographic distribution in

the family with A. chrysocephalus, which also is endemic

to the Hawaiian Islands. In fact, A. chrysocephalus is

known only from the Kona coast of Hawaii and Oahu. Geographic

limitation is not restricted to the above species, however,

as A. neoguinaicus is rarely found outside Fijian waters

(even though the original description came from a specimen

captured in New Guinea) and A. melanurus lineatus has

not been found outside the northern reaches of the Red Sea.

|

|

|

A male Anampses cuvier (bottom), even

at 10 inches of length, rarely consumes food items in

the wild over 4 mm in size. In my opinion, however,

the female (top) is more desirable due to their

magnificent beauty and smaller size. Photos courtesy

of John Randall.

|

Tamarin wrasses associate directly with

reefs for a number of reasons. These often small and delicate

wrasses rely on the rock structure for protection from larger

predators. Hiding within the rockwork is often their first

attempt at eluding a predator, but their best defense is undoubtedly

their unusual ability to bury themselves into the sandbed.

In addition to protecting them from predation, the sand becomes

their bed as the sun begins to fall.

The rock structure also holds the key to the Tamarin wrasses'

diet. Small crustaceans are readily plucked from the rocks

and crushed in their powerful jaws. In a gut analysis of A.

cuvier, the majority of the captured prey consisted of

small shrimps and amphipods, but copepods, isopods and brachyuran

crabs were commonly found as well. Additionally, a few fish

contained large enough quantities of polychaetes to warrant

special mention (Randall, 1972). The Tamarin's broad projecting

incisiform teeth aid in the capture of these small food items

while the pharyngeal plates do a fine job of crushing their

captured prey's shell.

|

Anampses lennardi

retains much the same color characteristics as it ages

from female to male. Lennard’s Tamarin is endemic

to western Australia and thus does not appear in the

American market with any regularity. Photo courtesy

of John Randall.

|

|

Most of the species are not easily located in shallow depths

- if they can be located in there at all. The best spot to

find a member of the genus is generally at depths ranging

from 50 - 100 feet. However, Anampses cuvier has been

captured in a mere six feet of water and thereby represents

the genus' shallowest occurring species. Juvenile members

of A. femininus have been seen in waters as shallow

as 20 feet, but adults can be found only below 50 feet and

become common at depths approaching 75 - 80 feet. Another

species with the same tendency is A. chrysocephalus,

whose juveniles are found at depths of 35 feet and adults

typically move deeper to depths of 65 - 75 feet.

Generally, these fishes form aggregations

of one dominant male and several (or more) females, and spend

the better part of their day feeding upon the reef. The males

are always larger and usually more colorful than the females,

and will flash or display more vibrant colors during courtship.

In all Anampses species the male is a different color

from the female. This two-phase coloration is called "dichromatism."

In some cases coloration varies between juvenile and sexually

mature females, thereby affording three separate color variations

in the same species.

|

Although collected only in limited locations, it is

expected that Anampses neoguinaicus is present

on other Pacific Islands such as Solomon and New Hebrides.

Although juveniles (bottom) are solitary fish,

adults tend to prefer loose aggregations. Photos courtesy

of John Randall.

|

|

No small males have been found, and thus it is presumed that

every male Anampses spp. is a "secondary male,"

that is, a male resulting from a female that has undergone

a sex change, also known as a "protogynous hermaphrodite"

(Randall & Kuiter, 1989). The largest and most dominant

females will change into males when the social order dictates

the need for a male. The death or capture of the previous

male is a sure-fire way to induce the most dominant female

to transform into the newest male on the block.

In the Home Aquarium

Successfully maintaining

a Tamarin wrasse requires a bit more skill than does the average

aquarium fish. Water conditions must be optimal and food options

plentiful, but perhaps the biggest obstacle to overcome is

obtaining a healthy and happy Tamarin. These beautiful wrasses

are often poor shippers and generally arrive at our local

fish stores' aquariums in a less than acceptable condition.

Therefore, careful inspection of the wrasse is the first and

most important step toward long-term success with this genus.

The most obvious sign of a stressful shipment would be damage

around the mouth. As these fish prefer to bury themselves

during stressful situations, it is not uncommon for the mouth

to be scraped, bloodied or even dislocated upon arrival. No

doubt, such specimens should be avoided. Assuming the fish

passes the mouth inspection, the logical next step is to continue

inspecting down the length of the fish, ensuring all its parts

remain fully intact. The fish should also be alert and swimming

with purpose. Finally, if the fish is consuming prepared foods

while still in the retailer's aquarium, it is a good bet this

particular specimen survived the shipping trauma with minimal

injury.

|

|

|

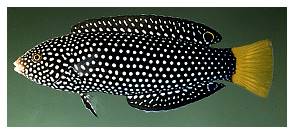

Anampses melanurus is a popular aquarium inhabitant

due to the magnificent coloration of both the female

(left) and the male (right). The relatively

small size of adult males at 4 inches is a bonus for

aquarists without enormous aquariums as well. Photos

courtesy of John Randall.

|

Although it is always wise to quarantine

every new purchase prior to its final addition to the show

aquarium, this particular step is especially important with

specimens of Anampses. The fish in this genus remain

predominantly shy upon introduction into a home aquarium,

and having to concern itself with fellow tankmates often delays

or permanently corrupts attempts at acclimation. Once the

fish is eating well, astute observation of the stomach should

be made. If the fish is eating well and still appears not

to be retaining its weight, medicated foods should be employed.

An estimated 75 - 85% of imported marine fish have intestinal

worms (Bassleer, 1996), and their natural diet, which consists

of eating mobile invertebrates inhabiting the substrate and

rockwork, often increases the odds that the fish will obtain

a parasitic worm. The stress induced by poor shipping practices

exacerbates this ailment, likely leading to the animal's death.

Normal signs indicating internal worm infestations are: weight

loss despite a healthy appetite, scraping or flashing against

rockwork or sand, and finally, a complete loss of appetite

occurring just prior to death. Treatment for internal worms

can be administered only to a fish that is eating. Live foods

are the best option for medicinal use, as they allow "gut

loading," which is the practice of feeding vitamins or

medicines directly to live foods just prior to feeding. If

live foods are unavailable, the next best option is to use

freeze-dried foods. The dry food will absorb and retain a

majority of the medicine. Piperazine is a good first choice

for treatment. Add 250mg per 100g of food each day for a period

of 10 days. Praziquantel or lecamisole can be used as a second

choice, with the same dosage and time frame. Niclosamide can

also be used at 500mg per 100g of food for 10 days (Bassleer,

1996).

|

|

|

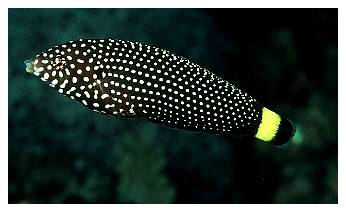

A female Anampses meleagrides (left) could

easily be confused with A. melanurus, but the

adult male (right) is twice as large and looks

nothing like either its cousin or female conspecific.

However, the male Speckled Tamarin could be confused

with the male A. geographicus quite easily.

Photos courtesy of John Randall.

|

When the time comes to add the new acquisition

to the show aquarium, several factors inside the featured

tank must be met to provide for optimum care. A plethora of

productive rockwork should be in place. By "productive"

I mean capable of producing enough micro-fauna to supplement

the prepared food diet. Anampses species continually

hunt for food and live, natural supplements should be considered

a quintessential part of their healthy diet. In addition to

the foods produced by a well-aged aquarium, the hobbyist should

expect to feed enriched brine shrimp or even gut-loaded live

brine, thawed Mysis species shrimp and flake or pellet

foods geared toward a carnivore's diet. Feedings at least

twice daily should be implemented in reef aquariums producing

a copious amount of natural foods; more frequent feedings

are required in aquariums that do not have an ample supply

of micro-fauna.

|

Quite a rarity for the Anampses genus, A.

twistii does not exhibit any significant color changes

based on its sex or age. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

The rockwork is also important for providing comfort and

security by offering a large selection of secluded hiding

spots. This is especially important upon first introduction,

as the fish will be weary and looking to protect itself. A

thick covering of sand is also a required décor. A

minimum of 2"of sand, preferably more, should be present,

which will allow the fish to dive into it and sleep for the

night. Without the sand the fish will likely injure itself

as it tries to bed down. Speaking of sleeping, you can expect

your Tamarin to go to sleep, and wake up, at nearly the same

time each day. Their internal clock is amazingly predictable.

At first, this might be a problem, as they are still functioning

on Indo-Pacific time. As the days and weeks pass, however,

the fish will slowly readjust their schedule to more closely

resemble the tank's photoperiod.

Mixing multiple Tamarin wrasses in the same aquarium can

result in a stunning display of a male/female pair. Due to

their dimorphic life cycle it is possible for three individuals

of the same species to look completely different from one

another. One caution should be exercised: do not add two males

into the same aquarium. A single Tamarin can be housed in

a standard 75-gallon aquarium provided all tankmates are peaceful

community fish. Mixing multiple Tamarins seems best served

by aquariums six feet in length or larger, thereby giving

each individual some extra swimming room.

Mixing Anampses species with other fish can be done

quite successfully, provided all tankmates are peaceful. Generally

speaking, Tamarins can sometimes act oblivious to the fish

around them, provided they are not interfered with. Small

gobies, cardinals, wormfish and other shy aquarium fish are

well-suited to aquariums whose largest show fish is a Tamarin.

If the Tamarin is not the feature fish and large or active

fish are featured, such as large angels or surgeonfish, expect

the wrasse to be not nearly as outgoing. Tamarins will not

fight for tank space and therefore can easily get pushed around

and take up real estate in hidden corners of the aquarium.

|

All age color stages of Anampses

lineatus are wonderfully amazing and attractive

aquarium inhabitants. Obtaining a juvenile (below)

would be ideal, thereby giving the hobbyist a chance

to view its maturation into an adult female (top).

The male's coloration, not pictured, changes from the

black of the female into a redish hue. Photos courtesy

of John Randall.

|

|

Compatibility

chart for Anampses species:

| Fish |

Will

Co-Exist

|

May

Co-Exist

|

Will

Not Co-Exist

|

Notes |

| Angels,

Dwarf |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Angels,

Large |

|

X

|

|

Some

angels may be too active or aggressive. |

| Anthias |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Assessors |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice; add the assessor first. |

| Basses |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Batfish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Blennies |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Boxfishes |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Butterflies |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Cardinals |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Catfish |

|

X

|

|

Catfish

grow increasingly aggressive as they grow larger. |

| Comet |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Cowfish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Damsels |

|

X

|

|

Some

damsels are too aggressive for Tamarins. |

| Dottybacks |

|

X

|

|

Some

of the larger dottybacks may choose to harass Tamarins.

|

| Dragonets |

|

X

|

|

Should

be mixed only in large aquariums that can supply natural

foods to both species. |

| Drums |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Eels |

|

X

|

|

Some

eels may consume Tamarins. |

| Filefish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Frogfish |

|

|

X

|

Frogfish

are capable of consuming juvenile Tamarins. |

| Goatfish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Gobies |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Grammas |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Groupers |

|

|

X

|

Groupers

will become increasingly aggressive and be able to consume

Tamarins as they age. |

| Hamlets |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Hawkfish |

|

X

|

|

Some

hawkfish may attack Tamarins. |

| Jawfish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Lionfish |

|

X

|

|

Some

lionfish grow too large and may consume smaller Tamarins.

|

| Parrotfish |

|

X

|

|

Often

too large and active to share a tank with Tamarins. |

| Pineapple

Fish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Pipefish |

|

|

X

|

Pipefish

are best suited for a species designated aquarium. |

| Puffers |

|

|

X

|

Best

avoided. |

| Rabbitfish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Sand

Perches |

|

X

|

|

Sand

perches can be aggressive, especially as they grow larger.

|

| Scorpionfish |

|

|

X

|

Scorpionfish

are best left to species tanks. |

| Seahorses |

|

|

X

|

Seahorses

are best suited for a species designated aquarium. |

| Snappers |

|

|

X

|

Aggressive

feeder; will intimidate Tamarins. |

| Soapfishes |

|

|

X

|

Best

avoided. |

| Soldierfish |

|

X

|

|

Should

do well except for the occasional bully. |

| Spinecheeks |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Squirrelfish |

|

X

|

|

Should

do well except for the occasional bully. |

| Surgeonfish |

X

|

|

|

Excellent

choice. |

| Sweetlips |

|

X

|

|

Some

sweetlips get huge, a potential problem for the Tamarins.

|

| Tilefish |

|

X

|

|

Some

tilefish can behave aggressively. |

| Toadfish |

|

|

X

|

Toadfish

may attempt to consume Tamarins. |

| Triggerfish |

|

|

X

|

Most

triggerfish are too aggressive for Tamarins. |

| Waspfish |

|

X

|

|

Waspfish

may harass juvenile Tamarins. |

| Wrasses |

|

X

|

|

Some

wrasses will co-exist, while others will not. |

Note: While many of the fish listed

are good tankmates for Anampses

species, you should research each fish individually before

adding it to your aquarium. Some of the mentioned fish are

better left in the ocean or for advanced aquarists.

|

This beauty was named Anampses femininus because

the female coloration (left) is more colorful

than the male (right). Also commonly called the

Blue-tail wrasse, no doubt based on the female's coloration,

these are highly sought after aquarium fish. Since juveniles

prefer shallow water and remain in small aggregations,

they can at times be an easy capture. They often move

from shallow inshore reefs to outer reefs at depths

of 100 feet. Photos courtesy of John Randall.

|

Sessile invertebrates are not at risk of

harm from Tamarin wrasses. These wrasses have no desire or

nutritional reason to consider prized corals as food. When

it appears they are harassing corals, they are more likely

chasing down a small hard-shelled mobile invertebrate which

has taken up residence within the coral, rather than harassing

the coral itself. Motile invertebrates, however, are another

story. Generally speaking, larger decorative invertebrates

such as Lysmata species shrimp, starfish and cucumbers

will not be harmed, but small ornamental shrimp are likely

to represent too great a temptation for the wrasse to resist.

Additionally, hermit crabs, Peppermint snails and Stomatella

species snails may begin to disappear at alarming rates.

Obviously, small hard-shelled invertebrates such as the various

copepods and amphipods found in aquariums will be vigorously

hunted. Tamarin wrasses are excellent predators; it is what

they spend their entire afternoon doing.

Meet the Species

Due to the limited

geographic distribution of a number of this genus' species,

very few species are well represented in the aquarium trade.

Those species that do find themselves the target of collector's

nets are undoubtedly the most geographically widespread members,

or ones that are located in key collecting areas.

One of the most popular wrasses in the

genus Anampses is A. chrysocephalus, the Red-Tailed

Tamarin. Unfortunately, the demand for this fish often outweighs

its availability as it is considered limited even in its native

Hawaiian waters. The female color variety is exceptionally

beautiful, and thus is the most commonly imported color phase

of this species. Given their potential adult size of six inches

and their preference for being paired with an adult of the

opposite gender, these wrasses can make for a wonderful display

in a peaceful reef aquarium.

|

The male's coloration (right) is likely the cause

for the common name given to Anampses chrysocephalus

- the Psychedelic Tamarin. Even still, the female coloration

(left) of this Hawaiian endemic is remarkable

itself.

Photos courtesy of John Randall.

|

The Blue-striped Tamarin is desirable merely

because its females' coloration is so attractive. In fact,

the female is so wonderfully attractive that it was named

Anampses femininus. Unfortunately for all hobbyists,

when this fish becomes available it is more often collected

as a mistake than actually being purposefully sought. These

fish are rather shy and reclusive, especially once divers

with nets make their presence felt on the wild reef. As such,

expect a very expensive price tag to be associated with them.

Even so, if you can track down a few members of this species,

an interesting and presumably rare captive harem can be observed.

Anampses meleagrides is perhaps

this genus' most often purchased member. Its vast geographic

diversity no doubt increases its overall availability. Thankfully,

its coloration is every bit as eclectic as the other Anampses

species and thus it remains quite an attraction to observers

and collectors alike. It can reach sizes up to nine or 10

inches; therefore, a larger aquarium may be needed when compared

to the smaller members of this genus.

Conclusion

Aquarists looking

to add an exquisitely colored fish to a community reef aquarium

should consider the Tamarin wrasses. Although their feeding

can sometimes be picky and often detrimental to keeping Dragonette

species, they do possess several characteristics which make

them an inviting inhabitant of most reef aquaria. Their generally

small size makes them ideal for most reef aquariums, while

their peaceful disposition lends ease to mixing them with

other small, peaceful community fish. With a few precautions

considered and dealt with prior to their purchase, hobbyists

can reward themselves with a stunning addition to their tank.

|