|

Introduction from

Eric:

A few days after reopening my

Coral Forum, I was greeted by an email from a member who

rightly pointed out to me that while he enjoyed my book

Aquarium Corals, several corals that had become

popular since its publication were not well-covered. He

specifically mentioned Acanthastrea. I cringed

a bit, but admitted he was right and promised an article

on this genus of coral in the near future. In fact, mere

days later I was visiting a local pet store in Houston

where a six to eight inch colony of a rather ugly brownish-gray

color had a $1000.00 price tag on it, and was labeled

as Acanthastrea. Other smaller colonies were present,

from a few polyps to small colonies that ranged from eighty

to several hundred dollars in price. A quick perusal of

live corals being sold on eBay (e.g., see here

and here)

and at mail-order vendors confirmed that many hundreds

of dollars are being paid for specimens of these corals.

I was and remain aghast! In this article, I discuss the

biology and husbandry of Acanthastrea, in addition

to providing some general ecological and trade-related

commentary. Anthony, in turn, will focus more on the handling

that occurs in the trade in this genus, including propagation

and potentially illegal activities in the name of profit.

Introduction from

Anthony:

At the IMAC 2005 conference, I

learned that Eric was writing an article about Acanthastrea.

Through that weekend's activities, we somehow struck upon

the notion to co-author the piece. I hope my contribution

will provide some information about how the aquarium industry

handles the mussids we know and love as "Acans."

I will discuss the farming and propagation of this coral,

as well as a bit of a reality check on the actual handling

of specimens from the exporting countries in an effort

to add a perspective of true value to keeping these aquarium-suitable,

sustainable and sometimes beautiful corals.

|

The appeal of colored Acanthastrea, like

many other mussids and numerous faviids, is quite

understable with specimens like this. Photo courtesy

of Amy Larsan (TippyToex).

|

Eric's Version of the Acanthastrea

Phenomenon:

In a way I feel perhaps responsible

for this recent fascination and concomitant exorbitant

price of Acanthastrea in comparison with other

corals. In this

thread, I mentioned it was one of my favorite corals.

In fact, if you search my forum, you will find that up

until midway through last year, most people were asking

for identifications of various mussids, some of which

were Acanthastrea, and some which I could not identify.

For an example, see this

thread. These corals have historically been misidentified

by hobbyists and merchants alike. They have been available

for decades, often being sold as unobtrusive "meat

corals" or "closed brain corals." Most

sat for weeks or months in dealer tanks as another of

the rather bland, massive corals that looked like all

the other brain corals. No one really wanted them, and

they sold for around $20-$30 at most stores, completely

misidentified. They were as commonly available as many

other genera of "closed brain" type corals;

more so, in fact, than Platygyra, for example.

Yet in merely a year, the hobby has suddenly bred a whole

population of people who have become taxonomists of the

genus, and who can look at these fleshy corals and affix

a species name to them, much the same as they do with

the genera Acropora and Montipora. It's

no coincidence that such armchair taxonomists also are

usually active traders or sellers: buyers beware.

See my articles on coral identification here

for such warnings. Ironically, consumers shelling out

hundreds or thousands of dollars for these corals at pet

stores don't even bother to bring a fifty-cent plastic

ruler with them to measure a corallite to see if the identification

is correct.

Previous conferences have showcased brilliant displays

of Montipora or Acropora. At this year's

IMAC, there were displays proudly showcasing Acanthastrea.

I asked one vendor if he wanted me to use it in a fragmentation

demonstration, and the look I got in return was one that

seemed to say it would be like cutting the Hope diamond

into stones for a simple eternity band.

This is not the first time such trends have occurred.

Early in the reef hobby days, Xenia species were

the corals of lore. To obtain or grow a specimen in this

genus was akin to finding the Holy Grail. But unlike Acanthastrea,

at least Xenia were legitimately uncommon ("rare"

in the hobby) because of their dismal shipping realities

from exporting countries. Now, they are considered a weedy

species, and handfuls of them are given away at aquarium

club meetings, and sometimes so many are produced they

are simply thrown in the trash. Then came Acropora.

Those who could obtain and grow Acropora were almost

worshipped, and to some degree this reverence for the

genus remains. Five-year waiting lists exist for tiny

fragments of corals that are positively bland or for those

that are among the most common species and color variants

on reefs. Yet, like Xenia, Acropora are

now considered a weedy, though still desirable, group.

As an example of this phenomenon, about a year ago, I

was honored to speak to the Los Angeles aquarium society,

and was shown a member's tank. As I stared at the tank,

the owner asked if I "saw anything special."

I scrutinized the tank, feeling as though I were missing

something. I looked left, and I looked right, and I looked

in every nook and cranny in an instant, feeling like I

was obviously obtuse in my observations of this tank.

I was finally pointed toward a small fragment of an Acropora

that was then explained to be one of the original and

few remaining fragments of the famous "Steve Tyree

Purple Monster." Without meaning offense, I must

admit it wasn't terribly purple. In fact, I have some

corals stuck in the back of my tank or lying on the sand

with more color than this infamous specimen. I see corals

with more color in most fish stores on a regular basis,

yet this coral apparently commands a price of several

hundred dollars for a centimeter or less. My impression

is that a lot of people in this hobby have simply lost

their minds!

Other similar stories of "fad animals" abound:

zoanthids, Ricordea, the Bangaii cardinalfish.

All have at various times been the newest trend for one

reason or another, the corals suddenly commanding outrageous

prices for a few polyps. In some cases, the truly rarest

corals are unrecognized in stores, or command prices so

low as to almost be given away. In other cases, the most

common species and color morphs are treated as gold. The

tragedy is that hobbyists fall into such traps and that

many people make small fortunes from deception and trendiness.

To elaborate on my comment about Acanthastrea being

one of my favorite coral genera; it is one of my favorites

because of the odd appearance many of its specimens have

on reefs. These specimens are often surrounded by sediments

and look like some random pieces of coral skin growing

on the reef. It is not the rarity or color of specimens,

but rather their oddity in nature where I have seen them,

that is among the reasons that this genus is one of my

favorites. I have lots of favorite corals, many of which

would be passed by in most stores. I love Anacropora

for its habitat and its delicate growth, yet some coral

farmers actually give this coral away free with orders

because it is just a rather boring brown shade. I also

have what I believe to be one of the rarest corals in

the trade; a species first described in only 1983, and

virtually unknown until the publication of Soft Corals

and Sea Fans (Fabricius and Alderslade 2001). It is

a warty and rather ugly brown soft coral of the genus

Dampia. Perhaps I could get a few hundred dollars

for a cutting of this coral? Maybe I'll try eBay!

To restate text I made for a ReefSlides

here

in Reefkeeping Magazine, Acanthastrea is

a relatively large genus in the family Mussidae, and contains

12-15 species. With the exception of A. maxima,

all of them may be found in the areas where coral collection

for the aquarium trade occurs. Acanthastrea species

are not easy to distinguish from species in several other

genera, and even families, of corals. They resemble other

mussid corals, specifically Micromussa, Mussismilia,

Symphyllia and Lobophyllia. They also resemble

some of the many species in the family Faviidae that may

be very difficult to tell apart. Recently, I also have

seen Blastomussa wellsi being sold as Acanthastrea,

and even Blastomussa have risen in price dramatically

in recent months, perhaps because of their resemblance

to Acanthastrea. Perhaps, and more hopefully, it

is because Blastomussa are collected at levels

that are questionably sustainable (Bruckner and Borneman,

2005).

In general, the mussids are corals characterized by large

corallites with large teeth or lobes on their septa. The

corallites generally have well developed columellae. In

terms of knowing if a living specimen is a mussid, it

is possible to see or gently feel the septa for the presence

of these large and often serrated-looking teeth. If they

are not present, it is quite possible that it is a faviid

and not a mussid. But, actual identification requires

examination of a skeleton devoid of tissue, and most mussids

and faviids are covered with heavy tissue that nearly

completely obscures their skeletons' diagnostic features.

If the coral is determined to be a mussid, species identification

requires measuring its corallites across their diameter

from wall to wall. Micromussa, which looks very

much like some species of Acanthastrea, has corallites

8mm or less in diameter. Acanthastrea generally

has corallites smaller than Lobophyllia, and most

have corallites between 8-15mm in diameter. Several species,

though, may have larger corallites and these are the ones

most difficult to distinguish from Lobophyllia

and Symphyllia.

|

With beautiful colors that positively overcome the

often bland colors of Acanthastrea, other

commmon mussids such as Symphyllia and Lobophyllia

are seen here in a Palauan lagoon. In the middle

photo, there is an Acanthastrea visible.

Can you find it? If not, how can you be sure that

the photos on websites or the coral in the store

is an Acanthastea, either? Photo by Eric

Borneman.

|

There is a reason for the above taxonomic distinctions.

Many aquarists mistakenly assume they have Acanthastrea

in their tanks. In fact, several of the photos in the

ReefSlides presentation are questionable, and may be other

species of other genera, including the faviid Caulastrea.

The same is true of corals on the Internet and in stores

being sold as Acanthastrea. Because these corals

have very fleshy polyps, identification even to genus

is difficult to impossible, as the characters that would

confirm a positive identification are hidden. Even if

Acanthastrea is the correct genus, assigning species

to these living corals is very, very difficult, even with

a bare skeleton. It should be assumed that any vendor

selling an Acanthastrea with a species name attached

to it probably hasn't the faintest idea if it is that

species or not.

|

A

typical small colony of what I believe is Acanthastrea,

photographed in Palau. Because I cannot see the skeleton,

I am not absolutely sure this is Acanthastrea.

Photos by Eric Borneman. |

With some exceptions, Acanthastrea are found in

many locations on the reef, and although some species

may be found much deeper, most are collected from shallow

water to about 20m in depth. They are frequently found

in somewhat protected locations or lagoons and may form

colonies that are anywhere from a few polyps to large

hemispheres to encrusting colonies several meters across,

although not all species are likely to form such large

colonies. Relative to other corals, they are similar in

shape, color and habitat distribution to most of the mussids

available in the trade, like the often staggeringly beautiful

Lobophyllia hemprichii, a coral that commands a

low price these days. Perhaps next year these will be

worth thousands of dollars? In Corals of the World,

Veron (2000) describes most species of Acanthastrea

as relatively uncommon, though I would not characterize

them as particularly uncommon in many of the coral collecting

regions of Indonesia. Such a designation is also given

to many species of Euphyllia, and while this may

be true across their range, they are quite common in coral

collecting areas (Bruckner and Borneman 2005). Ironically,

Acanthastrea lordhowensis, termed in the hobby

vernacular as "The Lord," is probably among

the most common of the species. It is almost funny to

see them described as "rare" by so many vendors

- an obvious deception of the public to market the species

at ridiculously inflated values.

|

Skeletal features of Acanthastrea must be

viewed to determine species. In this case, my Acanthastrea

skeleton sat in my sump for a long time before I

fished it out to add to my collection, and has been

covered with coralline algae making identification

difficult. I do not know what species it is, despite

being able to see many of the skeletal features.

Photos by Eric Borneman.

|

In the aquarium, as is typical for most Mussidae, they

are tolerant of diverse conditions and can thrive in strong

or subdued lighting and water flow regimes. They are voracious

predators with strong nocturnal feeding responses. Additionally,

they appear very competitive in their ability to extrude

mesenterial filaments in a coordinated manner, similar

to Hydnophora (as is seen in the last

photo of the ReefSlides slideshow). An aquarist on

Reef Central has provided photos

of this behavior in The Coral Forum that make her

colony appear related to SpiderMan. Therefore, care should

be exercised when placing these corals near other sessile

organisms that are desired to remain undigested by aggressive

Acanthastrea.

I am pleased to see that aquarists are taking interest

in species that were once considered uninteresting. However,

the hyper-overinflated values of these corals are a travesty.

For the price that a few colonies of Acanthastrea

and "purple monster" nubbins are being sold

at today, I could fly across the world on a long vacation

to Sulawesi, dive the glorious reefs that I love so much

in Indonesia, and with a little effort bring back Acanthastrea

I collected using existing exporters. The only thing is,

I probably wouldn't collect Acanthastrea. I usually

just swim right by them.

|

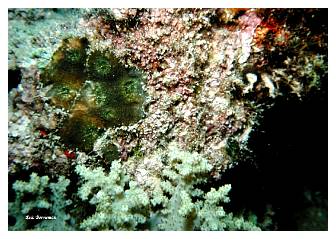

Let's play a game! Find the Acanthastrea

in this photo.

Photo by Eric Borneman.

|

Anthony's Comments on Acanthastrea:

Regarding the issue of industry

practices as it relates to the sale of "Acans,"

let me first address the response by a select few individuals

to my "Reef Trendy" article.

I was initially surprised to see a tiny outspoken and

angry minority of aquarists yelping in dissent, yet it

soon became very clear why the emotions flowed. We (hobbyists)

will kill our cash cow if we wake up and collectively

realize what's going on. The complaints were from a small

group of active "collectors" who buy, trade

and sell "Acans." These individuals are largely

working in collusion with each other literally to the

extent of price fixing, if you can believe the number

of aquarists we have heard from who discovered or keenly

suspected such activity and made it known to others in

the industry and law enforcement. The matter has been

exacerbated by some poached (pers. comm. US Fish and Wildlife)

corals making their way into the US trade. Price fixing

is when several competitive businesses conspire to reach

a secret agreement to set prices for their products in

order to prevent real competition and restrain the public

from benefiting from price competition. Price fixing is

a criminal violation of federal antitrust statutes and

also includes secretly setting favorable prices among

suppliers and manufacturers or distributors to beat the

competition.

So why did the "Acan" traders bark at my article

and other hobbyists' similar posts? The Ricordea

collectors did not peep, nor did the Acropora or

Montipora enthusiasts. The irony was that my article

barely mentioned "Acans" … certainly not

more than the other corals listed, or the top-shelf skimmers

in the same discussion. I think it has mostly to do with

the profit-driven and dubious marketing tactics, which

may include acts of collusion or secretly shilling each

other's sale/trade posts.

Which leads us to the crux of my concern that some readers

have failed to understand in my opinions on the "responsible"

trade in corals. Let me first state that I have paid hundreds

of dollars for individual corals and fishes through the

years, and if I could afford it - I might buy specimens

that cost thousands of dollars. Secondly, I have no problem

with buyers setting a market price (any price) based on

honest information and offerings! Indeed, hand-made Italian

sports cars command a higher price for two very good reasons:

value and limited production. And in turn, makers of mass

produced family sedans also earn their profits for the

very same reason: value. Based on the facts and merits

of a good or service, we each can fairly and individually

(often over a very wide range!) determine what we consider

"valuable" to us. But that is not what we have

here in some of the trendy coral frenzies. Instead, nefarious

merchants are calling corals rare that are not rare (more

about this below), or offering poached specimens. It's

not honest. It's not responsible. And it's not legal.

So is it really as simple as, "if you don't buy

it… they won't sell it?" Yes, but again this

is not an issue about forcing a drop in the price of beautiful

and expensive corals by consumer holdouts just because

we want to possess them. Indeed, we cannot all collectively

lower the price of those Italian sports cars simply by

not buying them and waiting for the price to fall. And

we cannot do the same for truly supply-limited corals

either. I am simply concerned about fraudulent sales at

any price, however harmless the misinformation may seem,

as with ignorant merchants that have never worked as an

importer or even been on a reef who are suddenly qualified

to call something "rare" in the hobby or

the wild.

|

|

|

Photo

by Greg Rothschild. |

Consider, for example, the sales of "Acans"

online by silent/secret auction? The act is not suspicious

in and of itself, but the skewed ratio of "Acan"

sales done this way overall versus other species of corals

sold without any secrecy is curious, if not concerning.

Furthermore, in some of those same listings, you can/could

find "Acans" listed as "not Indo."

Hmmm… that's odd. What does "not Indo"

really mean? It begs the questions of where they came

from, and why not tell us? If it was simply some other

legal exporting country, then why not say so? Or is there

some not-so-coincidental correlation to the formerly touted

Japanese Acanthastrea that "disappeared"

when the rumor got around that law enforcement was looking

for poachers? Apparently, a number of corals were illegally

exported from Japan under other names (Favites chinensis

and Goniatsrea pectinata) that were indeed Acanthastrea.

Because of the huge sums of money involved in this confiscated

collection and continued plans to continue the illegal

profit-making venture, investigations are currently underway

(Borneman pers. comms). It seems the conspiracy now extends

back to the countries of origin where some traders are

getting quite rich while collectors still get a few pennies

for collecting the same "closed brain corals"

they always have been collecting. Not surprisingly, poachers

have continued to bring in shipments of illegally obtained

specimens under such guises as Blastomussa. The

smuggled corals are so profitable that it is worth using

couriers to carry small quantities from Japan among personal

belongings! So the marketing game has now changed, and

some of those "Acans" labeled as "not-Indo"

do look remarkably similar to those Japanese "Acans"

offered previously. Again, it does beg the question.

By looking at the range of many Acanthastrea species

and the countries with coral exporting permits, we can

see that the range is predominantly Indonesia. These species

can and do exist in other areas, but we must ask ourselves,

"Is coral collection and trade allowed from those

countries?" If not, then the only Acanthastrea

that should be sold are legal ("Indo") Acanthastrea."

Looking at the CITES regulations, the legal range of collection

is clear. And when the office for the Ministry of Trade

in Japan says that Japanese coral exports for ornamental

sale are illegal (Calfo pers.comms), then that's also

good enough for me.

To conscientious aquarists, I ask if it is really worth

it? Why break the law that is designed to protect the

species and reefs that we admire which are under pressure?

What we are hoping, of course, is that informed, conscientious

aquarists will not support poachers, scammers or price

gouging. And surely the most tempted individuals can easily

console themselves with the fact that so many other, legal,

aquarium suitable species are available to more than satisfy

their desire to keep and observe beautiful reef corals.

Yet, still I lament the creation of (unworthy) hype for

so-called rare corals. It is much like the multi-year

waiting lists for species from some merchants, as Eric

mentioned above. Such lists are laughable to the point

of incontinence. They illustrate, at best, the grower's

ignorance of true coral farming harvest cycles, as well

as best-case production possibilities. At worst, such

lists betray some sellers' more nefarious side. Do consider,

however, that as a grower of "rare" corals,

if your goal is either to make the most money possible,

or to give away the most frags possible, doesn't it make

more sense to delay trades temporarily and build a bigger

fragment inventory from which to distribute them? Why

wouldn't a grower want to turn one frag into two, two

into four, four into eight and so on until the fragmented

colony reaches many hundreds or even thousands of clones

in a year or so (see my comments on the ease of fragmenting

"Acans" and their speed of growth)? What is

the logic behind merely scavenging two of four brood stock

pieces each month? This cannot even compare to the mass

production of a brood colony of even just 500 fragments

that affords the harvest of 50 pieces monthly, or more.

It should be apparent that a hearty production and productivity

at harvest would kill the long-term waiting lists in the

most delightful way for everyone involved.

Now, I can understand the desire of some folks with disposable

income to want bragging rights for not only the form (color,

species or whatever) but also the price paid for an animal:

a bit of elitism or luxury. We all have our vices - I

can appreciate that. But designer sunglasses, for example,

are "valuable" in large part because they are

limited in production. If you have any doubts, let me

invite you to entertain the notion of what would happen

if the $400 sunglass makers mass-produced their products

for cheaper cost and simultaneously stocked them in both

Wal-Mart stores and the finest boutiques on Rodeo Drive?

Ah… I can promise you that sales of designer sunglasses

at Rodeo drive stores would fall, like dropped jaws in

a church with a flatulent choir. The corollary to "Acans"

here is that unlike designer sunglasses, "Acans"

are not rare or limited. Really! Don't just

take my word for it… go to CITES.org (here

and here)

and see the export quotas for yourself. Review Indonesia,

for example, and look over this year and back at the last

several years reported. You will be dumbstruck to see

how many Acanthastrea were sent out relative to

many other (correctly perceived as) common corals! And

you will also notice the absence of quotas for stony corals

from Australia, Japan, USA and other such countries that

ban or restrict the collection of their stony corals for

export. If you also read the details of the quotas, you

will see that for many entries listed, there are actually

more than a few different species of the same genus that

can be lawfully exported under that given type species.

This is a practical and appropriate accommodation for

collectors and wildlife agents who largely, like ourselves,

cannot readily distinguish species between various Acanthastrea

species, for example, based on living examples of

stressed and retracted corals in shipment containers.

And so, this is why some import lists only have "Acanthastrea

echinata" listed, but other species are still

exported legally under the same name. This is also one

of the tricks that bogus sellers use to drive up their

prices. Ignorant customers see only "A. echinata"

available online, wholesale, or from their local retailer's

lists, but the "savvy" seller is promoting his

possession of a "rare" species.

Consequently, when we tell you that the genus is not

that uncommon in supply from legal exporting countries,

we really aren't kidding! And it has always been that

way. For example, I just got back from a trip to the South

Pacific to consult on a coral farm startup. Visiting with

the divers on the very first day, it was not surprising

or impressive to see them collect boxes upon boxes of

beautiful Acanthastrea. Not surprising, in part,

because they also brought up similar numbers of Faviids,

Euphylliids, Pocilloporids, etc. And because of the common

abundance and availability of these popular corals, it

should not surprise you that they all were priced the

same upon export! Yes, the gorgeous "Acans"

sold to L.A. importers for exactly the same price as brown

Favia brain corals, pink Stylophora, common

Fungia discs and everything else in the lot.

New coupons and digital deals from

Publix ad

have been released.

This is very much how the early supply side of the chain works:

reliable, consistent, high volume and relatively low profit

commodities. This happens week after week from the exporting

countries and has been going on for decades.

|

|

|

The typical appearance of Acanthastrea on

reefs in collection areas of Indonesia. Small isolated

colonies of a few polyps, unobtrusively forming

a skin-like covering over the substrate. One can

imagine the amount of hammer-and-chiseling of the

reef it takes to obtain such specimens. Photos by

Eric Borneman.

|

Just a month ago I was in Singapore, and the story was

the same. I spent many hours and days visiting local fish

stores, coral farms and wholesalers. Acanthastrea

were equally as common and plentiful as elsewhere. I saw

hundreds upon hundreds of specimens, and all for the average

price of any other coral, just like it used to be here

in the USA not too long ago.

The topic of trendy corals is not my principal or even

significant interest in the aquarium hobby. Far from it,

although straight talking is. But the issue really has

reached a crescendo beyond anything I can fathom. I just

checked the big online auction site, eBay, for a random

search of "Acanthastrea" and the first

item that came up (bidding to end July 30, 2005) happened

to be a 600+ polyp colony of 20+ pieces of these beloved

Mussids; the seller values his collection at over $75,000

and has offered it for "only" $17,500. For such

corals that enter the US for less than $10 each, I have

to ask at what point in the jump between $200 and $17,500

is it considered lunacy?

Propagation of Acanthastrea

A discussion of the fragmentation

of this mussid may seem… well, anticlimactic! But

at last, in this article, I am granted relief from a fetal

position where I've been laying for hours and chanting

"find a happy place, find a happy place!" A

safe, fun topic without controversy!

Acanthastrea is categorically one of the hardiest,

most tolerant and fastest growing stony corals I have

ever worked with. And mind you, I have worked with hundreds

of coral species, and handled many, many thousands of

specimens through the years. For anyone interested in

keeping and/or propagating Acanthastrea, you have

my strong assurance that it is a delightfully forgiving

and aquarium-suitable genus to work with.

The attributes that make Acanthastrea such a good

candidate for propagation are as follows:

· Large polyps

that feed heartily and can be target fed organismally

(use minced meats of marine origin: zooplankton substitutes).

Note: frequent feeding accelerates growth, recovery

and the harvest cycle.

· Distinct and conspicuous corallites that are

easily separable with minimal collateral damage to the

rest of the colony.

· Adaptability over a wide range of lighting

conditions, but especially tolerant of the heavy blue/cool

temperature spectrums that aquarists commonly favor

for aesthetics.

· Fast growth and popularity among aquarists

translates to good profits and appeal to commercial

farmers/sales.

Starting with judiciously cautious fragging techniques

of this coral, I have since learned an appreciation through

the years of how very tolerant this genus is to handling.

Presuming a propagation candidate is ideally well-established

(six months or more in the latest place of residence)

and well-conditioned (regular feedings, stable mineral

composition and quality of the water), success is almost

assured in your endeavors to propagate it! Without imposing

any significant change in lighting or water flow "post-operation,"

the fragmented donor and taken divisions will heal remarkably

fast. I have watched mine and others' heal in days and

grow out to be fully formed polyps ready for bilateral

division again in as little as two to three weeks. A one-month

cycle of harvest is, in fact, conservative when you start

with well-established specimens.

My preference is to separate individual polyps for faster

grow-out of the total colony's mass. Once divisions have

reached a sufficient size or polyp count for trade, they

may simply be glued or secured by traditional means (typically

natural settlement or superglue). I take polyps from wild

colonies by using bone-cutters or poultry shears. When

I'm feeling especially patient, I use a Dremmel or wire

saw (a diamond-coated "wire" blade used for

cutting curved shapes in stained glass or ceramic tile).

But if an individual polyp splinters or breaks with any

applied fragmentation technique… do not fear! Acanthastrea

is remarkably resilient.

**Click the picture

for a larger image and caption.**

As you can see in the images, I now resort to brutally

chopping individual polyps in half with a razor blade

or scissors. Polyps of this fabulous coral heal and grow

out in less than one month. Strong water flow and frequent

feedings are crucial for a fast harvest cycle, though.

Polyps can even be kept on the sand bottom as free-living

specimens. After a few "generations" of fragging

divisions, there is less/little carbonate mass underneath

each polyp; they are simply fast and loose on the "seafloor"

or your propagation tank. It is indeed remarkable to see

and feel the crushing of septa as a blade passes through

a polyp. Cuts can safely be made anywhere through the

colony and between the polyps. And please be reminded

that the successful propagation of each/any such corals

is a result of the demand for similar reproduction from

the wild. Acanthastrea is indeed a very hardy and

useful aquarium coral, even if/when its color is unremarkable.

Just remember to use these, and all, corals responsibly.

Concluding Remarks from Eric and Anthony

It would be nice if the profits

being reaped from the recent sales of Acanthastrea

stayed in the hands of the resource countries, and not

in those currently engaged in their trade at tremendously

inflated values. The hype could encourage smuggling and

other black market trades solely for the expectation of

great profits. For example, countries without permits

for the export of corals may begin to exploit their protected

resources, which otherwise may have been left undisturbed,

for the lure of the thousand dollar corals off their shores.

We have indeed heard of collectors in non-CITES countries

scheming to send their corals to CITES island nations

for rerouting to America. There sadly can be no mistake

about the impetus and responsibility for such unlawful

responses. We drive many markets, and this is not something

to be proud of.

|

|

|

Photo

by Randy Olszewski. |

Perhaps all corals collected from the wild, without real

evidence to ensure that they exist at sustainable levels

for continued collection, should command exorbitant prices.

As coral reefs continue to decline, there should be real

economic pressures on the sale of CITES-listed species,

but not like those described in this article. Perhaps

it's time for wild collected corals to be taxed so that

the tax levied goes into reef conservation efforts and

organizations. This type of action would encourage mariculture,

aquaculture and sustainable harvest practices. It would

also go a long way toward the long-established CITES provision

that trade in CITES species REQUIRES a non-detriment finding,

by a scientific authority, that trade in the species does

not occur to the detriment of the species' survival. In

the case of the coral trade, particularly those from the

major exporting nations, this is little more than an empty

statement since rigorous population studies have not been

conducted in most cases.

If vendors and buyers are interested in a coral because

it is rare, or the claim is made that it is rare, then

there should be a reduced demand by aquarists for

the species. The mission statements of all marine aquarium

societies I am aware of include language about stewardship,

conservation and sustainability. It is no longer considered

fashionable to have ashtrays made of gorilla hands or

umbrella stands made of elephant feet. The trade of ivory

is also banned in many nations. Why would vendors who

purchase booths and the aquarists who attend international

aquarium conferences, who themselves are almost invariably

conservationists, not be outraged at the sale of a "rare"

CITES-listed species, rather than desiring it or offering

it for sale? If indeed the species is truly not rare,

then such sales are based on lies, at best and fraud,

at worst. Price fixing of these (or any) desired coral

is also a crime.

Acanthastrea may be rare in some areas and more

common in others. Some species might be rare, in general.

There is little evidence, however, that they are any more

or less rare than the many thousands of other corals already

in the trade. It is always exciting when something happens

to create enthusiasm in the reefkeeping community; we

hope, however, that such excitement is based on new advances

and knowledge, not the over inflated and hyped demand

for this year's wild collected "coral du jour."

|