|

As young children

we learned about mythical animals that possessed supernatural

powers. Most of these animals resulted from the folklore of

centuries past; folklore whose intent was to scare mere mortals

or to attempt to explain natural happenings in our universe.

In recent years, however, these folklore stories have still

been told, but instead, the intent is more often to entertain

the reader or listener, rather than to explain the universe

or to create fear and respect. In the case of the genus Naso,

its species were awarded the common name, Unicornfish, because

of the single protrusion extending from their head- much like

the single horn found on the mythical animal's forehead. The

comparisons, however, end there, as these fish do not have

the hindquarters of an antelope or the tail of a lion. Grab

your favorite blanket and curl up into bed or gather 'round

the campfire - the tale of the Unicornfish is about to be

told.

|

|

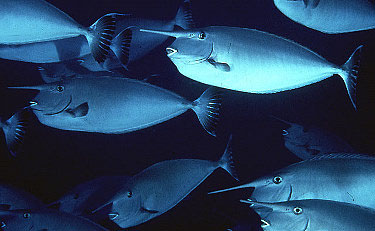

The largest of all Naso species is the White-margin

Unicornfish, also called N. annulatus. An adult

can reach up to three feet in length. Juveniles generally

remain as solitary fish and lack the namesake horn of

the genus. Adults are easily distinguished by the large

horn, and they often remain in schools as they cruise

the reef wall. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

Meet the Family

As Surgeonfish,

all Naso tangs are found in the family Acanthuridae,

which consists of three sub-families, six genera and seventy-two

species (Michael, 1998). All species possess at least one,

and possibly three or more, potent weapons just forward of

the base of their tail, on an area known as the caudal peduncle.

These weapons are similar to daggers and consist of modified

scales. Extensive tests have not conclusively shown any sort

of venom to be associated with these knife-like spines, but

it is important to note that in one series of observations,

every fish cut with the dagger of modified scales from members

of the sub-family Prionurinae died as a result of the wound

(Baensch, 1994). Luckily for us, fish from the sub-family

Prionurinae rarely make it into the hobby. Ichthyologists

use the caudal

peduncle as a distinguishing characteristic to place each

member into one of the three sub-families. In all three sub-families

the dagger is attached most closely at the base of the tail,

and extends toward the front of the fish. With most species

having two spines in their caudal peduncle, Naso species

are placed in the sub-family Nasinae.

|

Acanthuridae

- Acanthurinae

- Acanthurus

- Ctenochaetus

- Paracanthurus

- Zebrasoma

- Nasinae

- Prionurinae

|

|

However, three species in the genus have a single spine in

the caudal peduncle. This deviation from the norm of the genus

warranted the creation of a sub-genus. Originally, the subgenus

began as a valid genus named Axinurus (Cuvier, 1829),

but historically only one other author (Smith, 1951, 1966)

has recognized this genus as valid. When Randall (1994) reviewed

the three species of Axinurus he decided that the characteristics

Cuvier used to erect the genus were insufficient to warrant

being a genus, and reduced Axinurus to a subgenus of

Naso.

Smith (1955) is also responsible for naming another genus

within the subfamily Nasinae when he assigned two Naso

species to the newly erected genus Atulonotus. In his

1966 review of Nasinae, however, Smith utilized a total of

three genera in the Nasinae subfamily: Naso, Axinurus,

and the monotypic genus Callicanthus. It was at this

time that Smith also emended his description of Atulonotus

and placed it as a subgenus. Tyler (1970) disagreed with Smith,

and in his osteological review of the Acanthuridae family

he named only a single genus under Nasinae - Naso.

It is important to note that these variations in taxonomy

are based on skeletal and other morphological features. If

some researcher looks at the relationships as determined by

their genetic similarity, it is likely that the relationships

will change yet again.

|

|

The Horse-faced Unicornfish acquired its name due to

its short, rounded horn that develops on the adult fish.

As shown in the photo, this is a full-sized horn which

develops in this species. Naso fageni is fairly

uncommon in the wild and rarely shows up in the aquarium

trade. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

Naso species differ from other Acanthurids by having

fixed peduncular plates (in most Acanthurids the peduncle

plates are retractable) and three pelvic fin rays. Additionally,

they are noted to have highly specialized skeletal features

not present in any other Acanthurids. Another distinguishing

characteristic is their single, short-height dorsal fin, which

originates near the head and extends the length of their body.

Slim and pointed teeth number between 60-80 per jaw, depending

on the species and age of the fish. A total of 19 species

are now placed in the Naso genus.

|

Acanthuridae

- Nasinae

- Naso

- Axinurus

- caeruleacauda

- minor

- thynnoides

- Naso

- annulatus

- brachycentron

- brevirostris

- caesius

- elegans

- fageni

- hexacanthus

- lituratus

- lopezi

- maculatus

- mcdadei

- reticulates

- tonganus

- tuberosus

- unicornis

- vlamingii

|

|

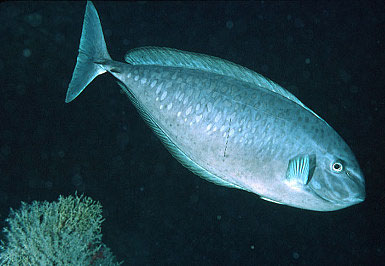

In the Wild

Naso species

are wide-ranging fish that are distributed throughout most

of the Indo-Pacific region. From the east coast of Africa

to the Hawaiian Islands, north from southern Japan and as

far south as the southern edges of the Great Barrier Reef,

Naso species have certainly made their presence known

throughout the Indo-Pacific. Having pelagic eggs and an extended

larval phase undoubtedly accounts for their vast distribution.

Most of the species can be found in water as shallow as 15

feet, and still others have been observed at depths greater

than 500 feet, but the majority of species prefer steep drop-offs

and reef walls occurring in the 40 - 120' range. The steep

drop-offs offer them easy access to the pelagic

environment. They are open water swimmers and most of

the species have a silver-blue color, presumably a camouflage

trait, which helps them disappear into the abyss against the

background of open ocean. Additionally, they have a unique

scale design, similar to that of sharks, which allows for

greater speed and easy swimming by reducing the turbulence

of water flow around the fish. The tough skin created by their

unique scale design was taken from the fish that were harvested

as food and used by native Hawaiians of the past as drumheads.

The pelagic environment is utilized only by adults, most

often in large schools, as they forage for zooplankton. As

juveniles, they generally remain close to the reef structure

and are found by themselves or swimming with other unrelated

species, with the exception of the schooling and pairing of

similar species by larger adults. Not only does the reef structure

provide protection for the young fish, it also provides food.

Juveniles are, for the most part, strict herbivores,

cleansing the rockwork of algae at a frightening pace which

allows for explosive growth of the fish. As the fish grow

their diet slowly begins to shift until the adults feed primarily

on plankton. In one particular gut analysis (Smith, 1951)

algae were undetectable, and as he stated, the gut contents

were "always a 'mush,' plainly animal tissue."

|

|

With a distribution restricted to the Hawaiian Islands,

Japan, the Coral Sea and the Lord Howe Islands, Naso

maculatus is perhaps the most geographically limited

species of the genus. Toss in the additional fact that

the Scribbled Unicornfish is a deep-dwelling species,

often found in waters more than 300 feet deep, and it

should be easy to understand why this fish will not

show up in your local aquarium store with any regularity.

Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

Sexual

dimorphism occurs in the genus and in its simplest terms

can best be described as males simply being larger. The horn-like

projection, which gives the genus its common name, is larger

on males, the streamers found on some species' tails are longer

in males, and the males' caudal peduncles are always larger

and more pronounced.

Naso species have an amazing ability

to change color almost instantly. While foraging for food

in open water Naso species adapt a color variation

similar to many other pelagic fish - dark blue, or even green,

shades concentrated at the top of the fish which slowly fade

to a shimmering silver as the view changes to the midsection

and finally merging into white on the bottom of the fish.

As the fish moves closer to rockwork or the substrate, the

blue hues are traded for colors more like the substrate. Like

so many other fish species, the males of the genus "flash"

intense colors during courtship. When Naso species

move into the cleaning zones of Labroides species wrasses

they become entirely pale, presumably making the job of finding

parasitic infections an easier task for the wrasse. Finally,

the fish are able to darken completely in times of anger,

fighting or aggressive behavior.

|

The Humpback Unicorn, Naso brachycentron, acquired

its common name by its humpback, which develops in both

the adult male and female. The fish in the photo is

only beginning to develop its hump; hence it is just

entering adulthood. Additionally, this fish is a male

as only males of this genus develop a horn. Photo courtesy

of John Randall.

|

In the Home Aquarium

Unicornfishes are

perhaps the hardiest of all Surgeonfish, and in this regard

they make great aquarium inhabitants. After all, they are

docile and fairly disease resistant. Their large size in conjunction

with their preference for open water swimming, however, dictates

their need for an incredibly large aquarium. Aquarium

size is perhaps the largest obstacle to overcome when attempting

to maintain a Naso species long-term. Small juveniles

acclimate without problems in aquariums as small as six feet

in total length, but if the aquarist's intention is long-term

care, a six-foot long aquarium will be woefully inadequate.

|

The One-spine Unicornfish is generally yellowish-green

in its mid-torso region during daylight hours, but the

photo shown here pictures the Naso thynnoides

during the evening hours when it adjusts its coloration

to hide among the rockwork. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

What is known from keeping these fish in

aquariums smaller than several hundred gallons is that the

end result will be a fish with stunted growth. Additionally,

the extent of the stunting is directly proportional to the

aquarium's size. Following Choat and Axe (1996) and the understanding

that Acanthurids obtain 80% of their growth in the first 15%

of their life, you can get an idea of how fast they should

be growing in your aquarium. Combine this with an expected

life span of 35 years (Choat and Axe, 1996) and we come up

with 80% growth obtained in the first 5.25 years. Let's take

this a step further and plug in the expected maximum size

for the popular Naso lituratus of 20". After doing

the math you can readily see that Naso lituratus may

reach 16 inches in length at 5.25 years of age. Following

the same reference, which states that the first 80% growth

is fairly consistent, it can be taken one step further: your

Naso lituratus should be 3.2 inches long after its

first year, and continue to grow three inches every year until

five years of age, when its growth will slow and nearly stop,

at which time it should be nearly ten inches long. This same

formula can help to determine the age of a newly imported

specimen. Keep in mind this additional point: Naso lituratus

is one of the smaller Naso species. Some other species

are capable of reaching nearly 40 inches in length. At this

point you should be adequately prepared to determine if/when

your Naso species has experienced stunted growth. The

decision on how to handle this situation is up to you.

|

|

Naso minor is the smallest of all Naso

species, hence attributing to both the scientific name

and the common name of Little Unicornfish. Their bland

coloration has never attracted the interest of the aquarium

trade, however. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

In an aquarium large enough to house a

Naso species, you undoubtedly will plan to have several

tankmates in the aquarium. After all, a tank that large would

look silly with only a single fish swimming around. The good

news is that Unicornfish mix exceptionally well with most

any other fish. They are passive and unassuming, but at times

are perhaps slightly overwhelming to most smaller fish. Their

large size and swimming agility typically concerns the smaller

fish, but in due time even the smallest fish will learn that

the Naso is not a potential threat. It would be wise

to have small, passive fish well-acclimated to the aquarium

prior to the Naso's addition. Larger fish typically

mix with Naso's very well, almost to the point where

it is not a concern. At times, it even seems like the Naso

surgeonfish referee the fights of other fish, sticking themselves

directly in the middle of the conflict in an attempt to break-up

the fight.

|

A juvenile Naso hexacanthus takes a moment to

pose for the cleaner wrasse. Juvenile Sleek Unicornfish,

as they are called by hobbyists and SCUBA divers alike,

is pale blue throughout; the caudal fin becomes a darker,

richer blue on adults. Additionally, adults grey-out

or even adopt a greenish color on the remainder of the

body except for the underside, which often develops

a yellow hue. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

|

Compatibility

chart for Naso species:

| Fish |

Will

Co-Exist

|

May

Co-Exist

|

Will

Not Co-Exist

|

Notes |

| Angels,

Dwarf |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Angels,

Large |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Anthias |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Assessors |

|

X

|

|

The

docile Assessor will likely feel threatened by the large

size and active swimming of the Naso. |

| Basses |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Batfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Blennies |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Boxfishes |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Butterflies |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Cardinals |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Catfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

co-exist well. |

| Comet |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. Add Comet first. |

| Cowfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Damsels |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Dottybacks |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Dragonets |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Drums |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Eels |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Filefish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Frogfish |

|

X

|

|

Although

mixing is possible, Frogfish adapt to captivity better

as lone inhabitants in the aquarium. |

| Goatfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Gobies |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. Add small gobies first. |

| Grammas |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Groupers |

|

X

|

|

Avoid

mixing a large grouper with a small Naso. |

| Hamlets |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Hawkfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Jawfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. Add Jawfish first. |

| Lionfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Parrotfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Pineapple

Fish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Pipefish |

|

|

X

|

Pipefish

are best kept in a species dedicated aquarium. |

| Puffers |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Rabbitfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Sand

Perches |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Scorpionfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Seahorses |

|

|

X

|

Seahorses

are best kept in a species dedicated aquarium. |

| Snappers |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Soapfishes |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Soldierfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Spinecheeks |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Squirrelfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Surgeonfish |

X

|

|

|

Surprisingly,

Naso species do well with other Surgeonfish. |

| Sweetlips |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Tilefish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Toadfish |

|

|

X

|

The

Toadfish will attempt to consume the Unicornfish. |

| Triggerfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates with all but the fiercest Triggerfish. |

| Waspfish |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

| Wrasses |

X

|

|

|

Should

be good tank mates. |

Note: While many of the fish listed

are good tankmates for Naso

species, you should research each fish individually before

adding it to your aquarium. Some of the mentioned fish are

better left in the ocean or for advanced aquarists.

|

Naso lopezi, also called the Slender Unicornfish,

remains widespread in the west Pacific Ocean, but rarely

finds its way into a collector’s net.

Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

Invertebrates, both motile and sessile,

are generally ignored by Naso tangs. On occasion, however,

stories are told of a Naso species wiping out an entire

crop of Xenia. Although this should not be regularly

expected, it has been known to happen. On those rare occasions

when this occurs, it seems the Naso tang and the Xenia

shared the aquarium for a quite some time before the surgeonfish

began feeding upon the soft coral. This is likely the result

of a fish that was not receiving enough food. Hunger will

force the best-behaved fish into taste-testing and consuming

foods which it normally would not.

|

|

Much like the Lipstick Unicornfish, Naso unicornis

transmits a signal to warn possible threats that it

will be a force to reckoned with. The blue spots surrounding

the caudal peduncles undoubtedly gather attention from

predators and divers alike and additionally have contributed

to its common name - the Blue-spine Unicornfish. Photo

courtesy of John Randall.

|

Food offerings should change as the juvenile

ages into adulthood. Like their wild counterparts, the juveniles

should be offered a diet rich in algae. Various types of dried

seaweeds, flake and algae-based pellet foods should be regularly

available throughout the day. Their fast metabolism in conjunction

with their active nature and their propensity for explosive

growth dictate the need for a copious amount of food - yet

another reason small aquariums are less than ideal for Naso

species. Several feedings per day are almost certainly required.

Additionally, you should expect the surgeonfish to enjoy grazing

on any naturally occurring algae in the aquarium. Although

Bryopsis and other types of "hair" algae

are generally ignored, Caulerpa species are often relished,

as well as Sargassum or Dictyota species. As

the fish ages and continues to grow, however, the need to

begin supplementing its diet with carnivorous foods will arise.

Frozen/thawed plankton and Mysis species shrimp work

very well for this purpose, but try to ensure a wide variety

of foods to minimize the chance of nutritional deficiencies.

Basically, expect your surgeonfish to eat just about any food

that enters the aquarium, whether it is specifically intended

for it or not.

|

As is easily seen from the photograph, this fish is

called the Silver-blotched Unicornfish. Scientifically

referred to as Naso caesius, it often remains

solitary as an adult or, on occasion, it will mingle

with Naso hexacanthus. Photo courtesy of John

Randall.

|

|

Meet the Species

Very few species

of the genus are found in the aquarium trade with any regularity.

This is due primarily to the excessive size reached by the

majority of the genus' adult fish. By far the most popular

member of the genus is Naso lituratus, also called

the Orange-spine Unicornfish. Besides being perhaps the most

attractive member of the genus, it is also the smallest, reaching

up to only 20 inches in length. The majority of individuals

imported for the hobby have their roots in Hawaii, despite

the fishes' large geographical distribution in the wild.

|

The Lipstick Unicornfish is the most commonly collected

and purchased Naso species for the aquarium trade.

Healthy adults of Naso lituratus will develop

long tail streamers, which make for a truly spectacular

display. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

At a considerably higher price, aquarists

can acquire the Indian Ocean Orange-spine Unicornfish. Ichthyologists

have awarded this fish a distinct species name due to its

limited geographic distribution and a slightly different color

variation than its Pacific look-a-like. Unlike the widespread

Naso lituratus, Naso elegans can be found only

in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, a factor that obviously

contributes to its inflated price tag. Overall adult size

is similar in both species, however. This species has been

long believed to be Naso lituratus, but the color differences,

as well as their differing ray and teeth counts, warrant two

separate species.

|

Rivaling the beauty of Naso elegans is the Big-nose

or Blue-lipped Unicornfish, Naso vlamingii. The

large size of the adult is unfortunate because the striking

beauty of the fish warrants much attention from aquarium

aficionados, and it is regularly imported for the hobby.

Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

Vlaming's Unicornfish appears at fish stores

only occasionally, but is common enough in the trade to warrant

discussion. Referred to as Naso vlamingii by ichthyologists,

this is perhaps one of the more aggressive species of the

genus once acclimated to the aquarium. Like all other fish

in the genus, adults typically remain 10 - 20 yards off the

reef slope foraging on passing zooplankton, yet remaining

prepared for a quick dash into the rockwork when predators

appear.

Oddly enough, none of the three aforementioned

species has the distinct horn which has yielded the common

name of the genus. It is, after all, not terribly common in

the genus with only three of the species acquiring it with

age - none of the juveniles has this spine. The Spotted Unicornfish,

Naso brevirostris, is one of the three species which

develop a very large spine and is perhaps the most attractive

member of the trio. It isn't until the fish reaches 10 inches

of length that the horn becomes apparent, but to acquire a

show specimen with a large horn, a 20 inch adult would be

needed; hence, none but the largest of show aquariums will

be able to support a fish displaying this trait.

|

|

The Spotted Unicornfish was so named due to the adult

male fish that is spotted throughout its body, something

which is only barely viewable in our photograph by looking

closely at the front of the caudal fin. Naso brevirostris

develops its horn at a much younger age than the majority

of other Naso species. Photo courtesy of John

Randall.

|

Conclusion

Unicornfishes can

be attractive additions to large home aquariums. Because

of their peaceful disposition and outgoing personality, they

regularly become the favorite finned inhabitant of hobbyists

who maintain them. The only considerable drawback to acquiring

Naso species is their large size, and the size of the

aquarium required for the fish to obtain its natural adult

size. Perhaps the purchase of a juvenile Naso is all

that is required to seal the impending purchase of that dream-sized

aquarium.

|

The single caudal penduncle, as seen in the above photograph

of Naso caeruleacaudus, designates this species

as a member of the Axinurus subgenus. Due to

their overall blue appearance, it has garnished the

simple, yet effective, common name of Blue Unicornfish.

Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

|