|

This month, I once again stray from the

strict topic of corals. Some projects I had started recently,

along with several posts during an extremely busy month on

The Coral Forum, gave me the idea for this column. Many years

ago, I wrote a pseudo-article for the old AOL Forum called

"The Reef According to Eric." It was a very popular

little piece, and I detailed what I felt were, at the time,

aspects of a successful reef aquarium. I updated it many times

over the years, but eventually it seemed unnecessary to continue

offering it because the information had become so widely known.

The present article will be based on the

"how-to" concept, but with a different tack. I offer

here some of my personal tips and tricks and suggestions for

reef aquarists in 2004. What I write is certainly not to be

taken as gospel, but rather as personal experience that I

hope will be valuable.

A Big Deal: The Acclimation of Corals (and

Other Things)

Frequently, I am asked about corals that

change in appearance or look poorly after being purchased

and introduced into a home aquarium. In particular, a coral

that looked healthy in the store is introduced into an aquarium,

often with what appear to be better conditions that those

in which it had previously resided, only to look in a remarkably

less healthy condition soon thereafter.

One of the questions I often ask in response

to such questions is, "Did you test the bag water or

the store water?" The answer is usually, "No."

Testing the bagged water is a lesson I learned quite a while

ago after enduring far too many inexplicable losses of otherwise

apparently healthy livestock. Most aquarists are familiar

with drip-type acclimations. The "old-timers rule,"

based on acclimating freshwater fish, is to make sure the

temperature and pH are slowly matched between the bag and

the tank, usually through the introduction of small amounts

of tank water to the shipping bag. This practice seems fairly

common with aquarists whose shipments arrive at the door in

a box, and somewhat less common with livestock brought directly

home from a local store.

Unfortunately, temperature and pH are not

always the whole story, and this is especially true of marine

invertebrates. To use corals as an example, I think most people

have experienced the relatively long period of time it takes

for the average coral to "open up" or acclimate.

For some, it may be a period of minutes while for others it

may ultimately take months. This "period of adjustment"

is a normal biological response of an organism to a new environment

and the changes that take place may be truly staggering in

terms of number and complexity. Most of the changes are unseen,

but are occurring nonetheless.

Acute changes may be obvious. For example,

if an animal is plunged from saltwater into freshwater, the

changes are usually fast and visually obvious in those animals

that manifest behavioral responses. To use a coral example

again, the rapid withdrawal of polyps is usually the first

response to adverse stimuli. Most aquarists would probably

agree that moving a coral from water that is 76oF, with 30ppm

of nitrate, a specific gravity of 1.021, 40 watts of fluorescent

light, and virtually no water flow to a tank at 82oF, a specific

gravity of 1.025, unmeasurable nitrates, 400 watts of metal

halide lamps, and strong water flow would be a stressful event

that would (and often does) lead to mortality of the organism,

despite the fact that the latter conditions may be more natural

and better for the long-term health of the organism. However,

behavioral responses under such conditions may include self-shading

by polyp contraction, sloughing of mucus tunics, catatonia,

and death.

What may (or may not) be surprising is

that many facilities that sell or trade in livestock have

water quality that is less than ideal. The animal or plant

purchased at any given time may or may not have spent some

considerable acclimatory period in another tank prior to it

being purchased by the aquarist. Upon arrival at that same

facility, the organism may have looked very similar to the

state the aquarist finds it in upon introduction to their

tank. Just because something looks healthy, does not in any

way suggest that it is healthy. A fish that eats at the store

may be eating because it is starving. A coral that is highly

expanded at the store may be expanded because it is starving

or receiving suboptimal light.

The point here, if it is not already obvious,

is that it only makes sense to know what the water quality

is from the tank or habitat from whence the organism came.

When I collect corals from the wild, I make it a practice

to either make subjective notes or directly measure water

parameters in order to most accurately reproduce those conditions

in an aquarium. When I get a shipment from anywhere, or when

I purchase livestock from stores, I ask the facility what

their water parameters are, or I directly measure water samples

from the packing container or bag.

There are two schools of thought regarding

acclimation; to remove an organism as quickly as possible

from the poor water conditions and into a tank with presumably

good water conditions, treating the shipping event as a temporary

acute stress; or to proceed in diligent, careful and slow

acclimations in order to pamper an organism through a shipping

or transient holding location, treating the event as a chronic

stress or an acute stress to which another rapid change is

intolerable. The choice of which method to utilize unfortunately

depends on the circumstances and the tolerance of the organism.

In general, I feel that if something has been in a store for

more than a few days and the water quality is significantly

different from the aquarists' tank, it has undergone some

degree of acclimation and can tolerate, and should likely

undergo, a longer more careful acclimation. If the store's

water is very similar to that in the destination tank and

the organism has been in holding or transit for less than

a day, a more rapid transfer to the tank might be preferable.

Things to Own

Over the years, I have bought, sold, tried,

accumulated, and disposed of a great deal of supplies and

equipment. Periodically, I find my closet and garage overflowing

with broken, unused, used, and useless parts and devices.

Unfortunately, most of the broken and useless things are aquarium

equipment. I have found a disconcertingly short lifespan for

most things produced by the aquarium trade. I have also found

that most of the really useful things I have for aquariums,

and which generally seem to last longer, are not strictly

designed for the aquarist. Most people probably have some

experience with this; it seems a trip to virtually any store

from the supermarket to eBay presents a smorgasbord of potentially

useful items for an aquarium! The following is a list of some

items that I feel are useful or even indispensable in keeping

reef aquaria.

Stereo or Dissecting Microscope

Honestly, most of the action and interest

happening in reef tanks is too small to see - or at least

see clearly. I really can't begin to express the worlds of

wonder that will open to aquarists with the use of a microscope.

To use a compound light microscope requires some degree of

experience, and also one generally needs some specialized

knowledge to appreciate higher magnification of most things.

However, a dissecting microscope is easy to use, practical,

and can be appreciated by even those without specific interests.

In particular, most aquarists are curious

to know the answer to the general question, "What is

it?" Identification of most things in the tank, from

corals to algae to worms and crabs, generally requires the

use of magnification. At the very least, magnification can

allow for the description of those things required for others

to answer the question, "What is it?" It can also

help the aquarist to determine, in some cases, reasons for

mortality or other problems in the tank.

PAR or Lux Meter

The typical reef aquarist spends hundreds

to thousands of dollars on lighting for their aquarium. Countless

hours of Internet forum, website, and catalog perusal are

spent determining lighting needs. Much of the interest and

concern is of relatively low consequence, and this is especially

the case when one really has no idea of light levels in one's

own aquarium. I am amazed how people will spend upwards of

$120.00 on a bulb, and hundreds of dollars on nonessential

equipment, but will not purchase or have even considered the

purchase of simple devices to measure light.

To be sure, lighting is a critical component

of most reef aquarium systems. It is equally critical to know

how much light is in the tank. There are now relatively inexpensive

devices available to directly measure photosynthetically active

radiation (PAR), and there are certainly very inexpensive

devices for measuring irradiance (lux). For half the price

of a 20000K HID bulb, a simple lux meter can be purchased

and used to determine light values in tanks, of various bulbs,

and how their output changes over time. There are, of course,

many differences in cost and quality of these light-measuring

devices, but even a $50.00 lux meter provides some real measurement

of light levels in aquariums. This, to me, is an essential

purchase for anyone concerned with reef lighting.

A lux meter is an inexpensive device to measure light levels.

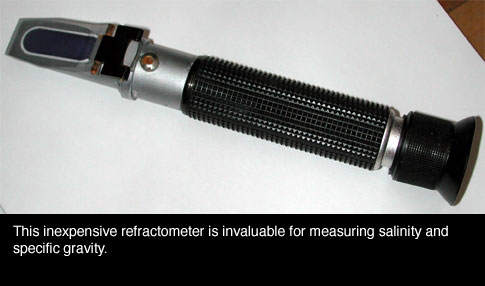

Refractometer

Having and using a refractometer is a no-brainer.

For years, aquarists have been offered and then lamented the

miserably inaccurate products available at low cost to measure

what is arguably the most basic and important parameter in

reef aquaria - salinity. While many organisms can manage relatively

short periods of salinity change, prolonged exposure to sub-optimal

salinity is literally a killer. I cannot count the number

of problems that have befallen others and myself through inadvertent,

unrecognized, accidental, or lackadaisical carelessness in

salinity measurements.

I think many people are probably aware

of the poor accuracy, especially over time, of plastic swing

arm-type hydrometers. Many floating glass hydrometers are

either cheap and inaccurate, or are expensive and accurate

but calibrated at temperatures far from those where reef tanks

are kept (requiring inconvenient and possibly inaccurate scaling

techniques to arrive at true salinity). Furthermore, glass

hydrometers are not convenient to use in tanks where they

are not easily stabilized and read because of water currents,

rocks, and tank walls. Conductivity probes are expensive,

require calibration, and give readings that vary from accurate

to inaccurate depending on any number of factors (see Holmes-Farley

2000,

2002).

Furthermore, conductivity does not measure salinity in parts

per thousand, or as a reading of specific gravity, which are

scales commonly used by aquarists.

|

However, there is now a ready availability

from aquarium sources of devices called refractometers that

are generally quite accurate, easily calibrated, extremely

quick and easy to use, and inexpensive, to boot. I say this

loosely, since I regularly use a refractometer that is not

inexpensive at $280.00, but I also have one that reads identically

to it and costs $69.00. Most of the refractometers available

in the aquarium trade today are also temperature compensated

so that no special calibration is needed for temperatures

of reef aquaria. They are a lifetime investment, require little

care or maintenance, and are so easy to use that accurate

salinity measurements can be taken daily in a matter of a

few seconds. I cannot fathom any reason why any aquarist should

not have one of these devices in their aquarium repertoire.

pH Pen

Another no-brainer is the purchase of a

pH pen. During the course of only a few years with regular

testing using colorimetric reagent tests, one could have paid

for the purchase of an inexpensive "pocket" pH tester.

As with salinity, pH readings using various reagent-based

tests are variably accurate. Even though the standard reagent

pH test is one of the easier tests to perform, I think I speak

for most hobbyists when I say that getting out little bottles

and tubes is not something I want to do more often than I

have to. Although pH readings are highly variable and important,

I think its safe to assume most people would take this reading

more often if it took seconds rather than minutes.

There is a wide range in cost and quality

of devices made to measure pH. However, inexpensive pen-type

pH probes are readily available, many for under $50.00. This

is about the cost of five reagent pH tests, and the pH pen,

used properly, will last for years or decades. Their calibration

is quick and easy, and taking pH readings of tank water takes

approximately 5-10 seconds. I store a pH pen upright with

its cap filled with pH 7.0 buffer beside the tank. I remove

the cap, swish the pen in the water and take an accurate reading

within seconds, rinse the pen under tap water, put it back

in its cap, and I'm finished.

|

I had always been too lazy to sit at a

table for an hour testing various water parameters with reagent

kits in the aquarium hobby. I hate little bottles with randomly

sized drops, tiny little packets of powders that rarely all

come out of the package, tiny plastic tubes that you can't

see through in a few months, glass tubes with openings so

narrow you miss the opening with the products you try to add

to them, little stoppers that leak, color charts that do not

match the results of the test, and reagents that go old within

the time frame of my using them up. I am pleased that some

lines of tests today are more accurate than when I began testing

tank water with reagent powders and drops, but they are certainly

no less inconvenient. Consequently, I rarely tested water,

and sometimes I should have. This is more the case with the

important parameters, of which pH is one. Any inexpensive

device that saves me money in the relatively short term, provides

accurate results, lasts a long time without replacement, and

makes my aquarium maintenance life easier is a good thing.

I suspect it would be the same for most other aquarists, too.

|

250, 500, 1000ml Graduated Beakers

Yes, measuring cups, bowls, glasses, and

plastic cups work just fine to make additions to tanks. However,

believe me when I say that using Pyrex beakers in these three

increments, coupled with a Sharpie pen to mark on them, will

be very appreciated when measuring, pouring, and adding any

number of dry or liquid substances to aquariums. In addition

to thanking yourself a thousand times for the many aquarium

uses found for them, the limitless other household uses will

never cease to amaze.

Magnifying Lens

If the stereo microscope mentioned above

is not an option at the present time, the use of a good quality

magnifying glass, loupe, or lens will suffice. I cannot think

of any reason why one should not have one of these for looking

in the tank, examining things after taking them out of the

tank, or for helping in identifications. The only downside

to magnifying lenses is that one can look just a little "geeky"

when observing the tank, face pressed against the glass, and

friends and family may truly begin to wonder about you. If

anyone wants to go a little more overboard, consider the purchase

of a ring-light magnifying lamp that can be purchased from

office supply stores. These can be clamped on the edge of

a tank or stand and simply swiveled to examine all creatures

great and small under lighted 10X magnification or more with

a big viewing area.

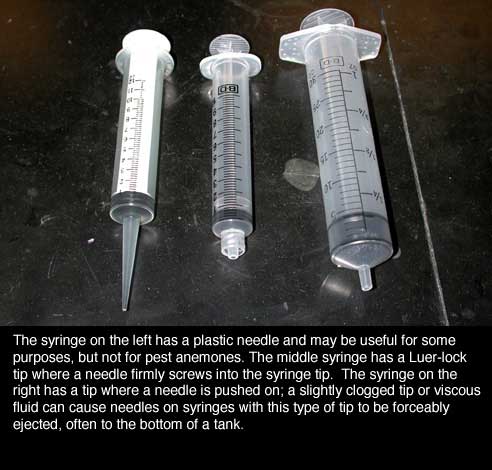

Syringes

Syringes are invaluable to reef aquarists,

if not only for their usefulness in attempts to kill Aiptasia

anemones. Unfortunately, most syringes readily available to

the public come without needles (a most useless equivalent

of a small turkey baster), or with needles that have a square

cut end that are not really made for injection (such as those

from home improvement stores). But, syringes are not illegal,

they are not by prescription only in most places (despite

what many pharmacists may tell you), and you can get them.

Insulin syringes are great. I prefer 1-3 cc syringes with

luer-lock ends where one can simply replace the needles. Luer-locks

also prevent viscous solutions or clogged needles from being

blasted off the end of the syringe and falling to the bottom

of the tank when forcefully ejecting a liquid. For assorted

gluing jobs, I use one-time-use syringes with a larger bore

needle to fill with superglue after the cap has become cemented

onto the tube following several cap re-openings, when one

cannot get the remaining glue out of the tube without tearing

the plastic cap and twisting the metal tube to some unrecognizable

and useless lump of metal with half the product still inside.

A simple prick of the tube and a pull of the plunger and I

am back in business.

|

Yes, you might feel like a junkie asking

for them in the prescription area of a drugstore. I have bought

countless boxes and bags of insulin syringes, and felt like

Sid Vicious every time I asked for them. I tended to buy a

box at a time to avoid going through this anymore than I had

to. However, there are online and other sources for syringes

(lab supply, veterinarians, etc.) that do not involve such

situations as being asked to present diabetes cards, asking

what use you have for them (and explaining to a pharmacist

what an Aiptasia is, exactly, and how they are so evil

they must all be exterminated with hydrochloric acid), or

wearing short sleeves in the middle of winter to assure everyone

that you are not hiding track marks. Remember that the larger

the number of the needle gauge, the smaller the needle is.

For example, a 12-gauge needle is like putting a firehose

on a syringe. Fit one with a 29-gauge needle, however, and

the Aiptasia will not even notice until its mesenteries

are boiling!

Digital Camera

Without question, these are among the most

important inventions since the computer. These devices make

it possible to easily document tank events, share photos,

acquire online help, sell items, and even illustrate online

aquarium magazine articles! Best of all, it is now possible

for even rank amateurs to take really good aquarium photos

without the ridiculous amounts of special techniques that

were once required with the use of film cameras to get an

only somewhat blurry photo of one's pride and joy aquarium.

I still have quite a few film cameras - nice ones, too. They

mostly collect dust now. I like the idea of film photography,

and enjoyed doing it. But, for most purposes, I say "purist

shmurist." I'll take those 192 high-resolution clear

images on a 128MB card that costs the same as a few roles

of unprocessed Velvia any day of the week. Digital images

are easily formatted, saved, shared, shrunk, published, emailed,

printed, cropped, and Photoshopped. I have the use of an extremely

nice slide scanner at my lab, and have a darn nice scanner

in my home. It takes about 5-10 minutes to scan a single high

resolution slide that still lacks the vibrancy of a digital

photo and in no way provides what the original slide showed.

Today, I really have no use for slides whatsoever. They sit

in boxes next to my film cameras. If anyone wants to take

pictures of their aquarium, in my mind there is no substitute.

Back-Up Power Supply

See below.

Arm & Hammer Super Washing Soda and Mrs. Wage's

Pickling Lime

My calcium and alkalinity (calcium and

carbonate) products of choice. About a dollar a pound for

both, and I get them at the same grocery store where I will

buy my dinner. What more needs to be said?

Things to Measure

Aquarists tend to busy themselves testing

their water. This is a good skill to have, and although a

careful eye can often surpass the readings of water tests,

some parameters require regular monitoring. The standard series

of tests that most people perform on reef tanks seems to include

the following: ammonia, nitrite, nitrate, pH, calcium and

alkalinity. There are many other tests, and "testy"

persons may include iodine, magnesium, boron, strontium, phosphate,

and other inorganic and organic compounds in their "chemistry

duties." My feeling is that while they all may be worthwhile,

some are more valuable than others. In particular, ammonia

and nitrite, unless the tank is new or has been disturbed,

should always be unmeasurable by most test kits. I only use

these tests under unusual circumstances. Nitrate can be a

bit more problematic in tanks, especially new ones, but is

becoming less of an issue as better aquarium methods become

almost commonplace. Still, judging by many posts in The Coral

Forum, it seems most aquarists are regularly measuring these

substances, and failing to measure others.

Phosphate

Phosphate is often a problem, and has fairly

serious consequences to reef tanks in any but nearly unmeasurable

levels. I will not go into any depth on the subject since

it has been well covered elsewhere (Holmes-Farley

2002). Although many people measure it, I would estimate that

the majority of aquarists do not. In my experience, poor coral

growth, undesirable algae, and a tank that lacks vitality

is often found to have elevated phosphate levels. I would

suggest that this, or any standard water quality tests, be

used regularly, especially by those who are relatively newcomers

to reef tank husbandry.

Alkalinity

If I could name a single water quality

parameter that is observationally the best indicator of a

healthy tank, it would be alkalinity. Tanks with high alkalinity

are generally ones that are doing well. Again, the subject

of alkalinity has been treated elsewhere (Holmes-Farley

2002), and its co-function with calcium in producing the products

of calcification is well known. What is worth mentioning here

is that calcium, despite rapid depletion, is rarely limiting

to calcification in seawater because of its very high availability.

Alkalinity, however, is also rapidly depleted in tanks, and

can be limiting to calcification. I rarely test calcium because

I know from experience and my regular maintenance that I am

adding a lot of calcium and I know it is at levels that make

it readily available. I do, however, test alkalinity regularly

on many of my tanks.

Ironically, and perhaps because of its

rate of depletion in the small water volumes of aquaria, natural

seawater levels of alkalinity are, in my experience, suboptimal.

I prefer to keep my aquaria at levels much higher than seawater,

and have seen no downside to doing so. On the contrary, if

my tanks fall to seawater levels (about 2.9 meq/l), the tanks

tend to look very poorly indeed. I strive for alkalinity levels

somewhere between 4 and 5 meq/l, and the results of such elevated

levels seem to indicate that reef aquaria thrive with the

additional availability of carbonates. Furthermore, it helps

to buffer against swings in pH values.

Oxygen

In an upcoming article, I will be covering

the subject of oxygen dynamics in aquaria. Without question,

oxygen levels are critical to survival of our captive marine

species. Anyone who has experienced even a relatively brief

power outage understands how quickly animals begin to die

in stagnant tank water. Oxygen levels also drop precipitously

at night, and this is especially true with tanks that are

either densely stocked or have with poor gas exchange (for

various reasons). Yet, rare is the discussion of ways to measure

oxygen, and few aquarists I know have ever measured oxygen

in their tanks.

I use an expensive oxygen field probe,

and it would be impractical for most aquarists to own such

a device. However, oxygen probes are available to the hobby

at somewhat reasonable prices. They are not inexpensive, but

given how important oxygen is to the life in our tanks, it

seems a reasonable cost. Much more practical, if not slightly

less accurate, are colorimetric tests that are available from

many aquarium test kit manufacturers. I would suggest that

oxygen is something that should be tested for in aquaria far

more often than it is.

The Tool Shed

When one first begins keeping an aquarium,

the fish store is the source of almost all the dry goods and

equipment purchased. Over time, however, I can almost guarantee

that Home Depot or Lowe's purchases will exceed those spent

at fish stores, except perhaps on livestock. This section

is truly the insider's guide. Trust me when I say that these

things will be used, will come in handy, or will almost without

exception be required at some point during the lifetime of

a reef aquarium.

Plumbing

-

PVC pipe and various fittings, including

elbows, couplings, male adaptors, barbed fittings, and

female adaptors. At least five of each type, both slip

and threaded, in all the common pipe sizes of 1/2",

3/4", 1" 1.25", 1.5" and 2" should

be kept on hand at all times. Also, one full length of

each of the pipe sizes should be on hand.

-

a PVC cutter and a hacksaw for the

larger sized pipe

-

an eight foot length of flexible vinyl

tubing in every size from airline to 1" inside diameter

(and stainless steel or plastic hose clamps to fit the

tubing).

Adhesives

Electrical

-

wire strippers

-

wire nuts - a box of each of several

sizes

-

electrical tape - numerous rolls

-

cable ties (lots of these, in different

sizes)

-

coax staples for tacking up cords

-

power strips and extension cords (at

least five of each)

-

ground fault interrupting outlets if

not already in place

Tools

-

stainless steel wire cutters. Do not

even bother to spend the money on steel ones. They will

rust after one or two uses to the point where they cannot

be opened, and you cannot put oil on them to free them

up because the oil gets in the tank.

-

small wood chisels

-

Dremel-type tool with various cutting

blades

-

hole saw kit with various size hole

saws

-

acrylic cutter for scoring plastic

or an acrylic blade for a table saw, Dremel tool, or jigsaw

-

single-edge razor blades (a 100 count

box is the best idea)

-

some form of power screwdriver

Materials

-

several sheets of eggcrate

-

fishing line

-

a 2' x 4' sheet of at least 1/4"

Plexiglas or acrylic

-

an assortment of nylon and stainless

steel nuts, washers, and machine screws

-

plastic scrubbers for dishes

-

various sizes of Tupperware-type containers

-

several Rubbermaid-type bins, at least

20 gallons in size

-

pint, quart and gallon containers or

bottles

-

Ziploc-type freezer bags in quart and

gallon size

-

rubber bands

-

Sharpie permanent markers

Little Things

The following is a list of little truisms

I have found to apply quite often in reef aquarium husbandry.

I think they will prove useful many times over lengthy periods

of time.

When in doubt, do a water change - or two.

Then, watch and wait.

Have a functioning and functional quarantine

tank for all newly acquired livestock, and for established

livestock with problems that need attention.

Algae and cyanobacteria happen, even under

ideal conditions. If nutrients are low, and grazers are adequate,

algae still happens sometimes. They can also go away as fast

as they came, and sometimes waiting is better than intervening.

When confronting things that are not recognized,

it's probably best to figure out what they are before deciding

that they are bad and destroying them.

Aiptasia anemones are really horrible

pests. They are the poster children for why quarantine is

so important. I have, since beginning my first reef tank,

been plagued with them and they have killed, or caused me

to kill in my efforts to get rid of them, hundreds of corals

and other organisms. I have spent hundreds of hours and hundreds

of dollars fighting them. I have succeeded three times in

eliminating them from my tank by various means. Each time,

I have inadvertently reintroduced them. If you have them,

good luck. If you see one, kill it thoroughly or (and I am

not joking) get rid of whatever it is on. Just throw it out

- the rock, the coral, or whatever. If you do not have them,

I would strongly suggest quarantining EVERYTHING to avoid

getting them. I reintroduced them on pieces of algae once!

The pedal lacerates can be very small and not even visible,

but will be noticeable within a month. I cannot stress enough

how much everyone wants to avoid having these anemones in

their tank.

Keep your hands out of the tank as much

as possible, and resist the temptation to move things or add

things any more than is absolutely necessary. It's best for

reef aquaria to be left alone as much as possible.

Spend as much time watching and growing

and reproducing things, and spend as little time buying things,

as possible.

Don't place too much faith in what the

majority of the aquarium hobby has to say! Just listen, smile

a lot, and make sure what you have heard or read is the truth

(see Shimek

2003 and Borneman

2003).

Nothing speaks quite like experience,

although experience gained through advanced learning and planning

is a good thing.

For persons about to purchase their first

tank, get one at least twice as big as the one you are considering.

Only when you are really proficient will the idea of a small

tank be a reasonable and practical endeavor.

I'm not a big fan of aquarium equipment,

in general. However, there are two things that should not

be compromised, and they are both expensive items and important

items. Believe me when I say that every ounce of pain that

comes from emptying a wallet on good pumps and good lighting

will be the reason for a sigh of relief many times over.

Aquarium Products

I rarely endorse products. In fact, I have

made it a practice to avoid any sort of product endorsements,

and my nearly constant deriding of such things for the past

decade has probably resulted in my being permanently blackballed

from the good graces of many companies who would otherwise

be sending me free products and reimbursement for my marketing

prostitution. Nonetheless, I don't care and I never have.

I really couldn't even begin to say how many different devices

and products I have bought or tried over the years. So here,

for perhaps the first time ever, I am going out on a proverbial

limb and giving a thumbs-up to the following products that

I have used for enough time and for many times and I think

deserve credit where credit is due. I offer my apologies to

those not mentioned, but it is not possible to try, use, or

know every product available.

Similarly, I refuse to mention those many

products that deserve a "Golden Garbage Pail" award.

Be warned: this is a short list.

Aquarium Systems MaxiJet Powerheads

These things "take a licking and keep

on ticking." I have some of my first powerheads that

still run, despite my splicing on new plugs where I melted

them in wet power strips. Sometimes you have to smack them

to get them to run, the impellers sometimes shear and need

replacing, and the suction cups….well, they suck! They

deteriorate fairly quickly in seawater (but, so do all the

other brands, and usually faster). Some of my first Hagen

powerheads still run, too, but their flow rate for unit size

is awful (though adjustable flow control is nice). But, in

my experience with (I think) multiple kinds of every power

head made over the past decade or so, these are the best and

always have been. A few little fixes (hint, hint) and they

would be nearly perfect, for what they are.

Tunze Stream Pumps

I hesitate to mention these, since they

are relatively new, and I have only used a few of them. I

am deeply disturbed by their cost, and absolutely stunned

at the cheapness of the materials and mounting devices. Still,

to use the vernacular, "these pumps rock." The water

flow is stunning, pump efficiency is beyond anything else

available, and they have run constantly despite my intentional

and unrelenting abuse. One stopped working briefly until I

dissolved the heavy calcium deposits from around the magnet

assembly. Several months ago, I even broke one of the cheap

plastic pieces, and lost an o-ring from, well, somewhere,

but I plugged it back it and it ran like a charm. These pumps

represent one of the major triumphs of water flow issues since

I began keeping reef tanks.

Cyclop-Eeze©

and Golden Pearls

Never before have there existed such excellent

plankton substitutes for small mouths. Subjectively, there

is no single product I have used that appears to have provided

such dramatic results.

Protein Skimmers from My Reef Creations™

The cost of good protein skimmers is an

abomination. The idea of most aquarists spending upwards of

$750 or more on a piece of plastic through which air and water

move is unthinkable to me. I have found the quality and performance

of skimmers from this company to equal or surpass those of

the "name brands." While not cheap, they are a veritable

bargain by comparison.

Livestock from Tropicorium, ORA, and Inland Aquatics

Livestock from these places doesn't die

without a lot of assistance from an aquarist. I won't go into

the many reasons why this is probably the case, but a lot

stems from the care and expertise of the owners and staff.

Order accuracy, availability, color, selection, price, and

eccentricities aside, in my mind the aquarist could do no

better in their choice of a livestock supplier based on standards

of health, survivability, and ethics than those listed above.

Emergency Readiness

It is only a matter of time before an aquarist

faces some sort of accidental disaster. Such events seem to

happen more frequently when one is not at home, of course.

I have personally had massive tank disasters happen more than

I care to admit. Some of them were unavoidable, others were

not. Each time, after ameliorating further losses and restabilizing

the tank, I took various steps to ensure that another similar

event did not occur. Unfortunately, all too often I used a

"bandage and a prayer" rather than truly taking

steps to prevent future problems, and predictably, I incurred

further losses at various times afterwards.

|

I can't express how heartbreaking it is

to lose animals nurtured for many years, and this is doubly

so when the reason for their death lies squarely in one's

own hands. The financial losses alone can be extraordinary,

the time spent growing or breeding or caring for various species

is lost forever, and the loss of life is tragic. I would add

that in my own case, and with most events I hear about, power

failures are the most common reason massive aquarium losses

occur. It is nearly impossible to ever be prepared for every

contingency, but given the most likely scenarios, I would

suggest the following:

|

Keep

the following extra items on hand, beyond what is immediately

being used:

|

Extra salt

|

- at least enough to prepare

the same amount of water as the volume of all

tanks in the house.

|

|

Medication

|

- I try to keep a broad-spectrum

antibiotic, medicated foods, Lugol's iodine solution,

and "Liquid Bandage" on my aquarium

shelves for those fortunately rare cases where

their use is warranted.

|

|

Water

|

- I would suggest keeping at

least ten gallons of clean freshwater available

at all times. The numbers of times I have quickly

had to use at least this water volume for one

reason or another are uncountable. Were I to have

waited for an RO unit to produce this volume,

or had to go to the store and purchase water,

serious losses could have occurred.

|

|

Containers

|

- I would store at least enough

plastic bins or tanks to house every organism

in the tank, even if extremely crowded, for a

few days.

|

|

Pumps

|

- An extra submersible pump

capable of turning over the water in the tank

in the event of failure of the main pump is a

very wise idea. I've found that having an identical,

back-up main pump is also good planning. In addition,

at least one powerhead should be dedicated for

each of the bins or containers mentioned above.

I would also keep one extra impeller for each

pump or powerhead in the tank. In most cases,

tank inhabitants can be kept alive for many days

or even weeks in just circulating (and heated)

seawater, with no lights or filtration.

|

|

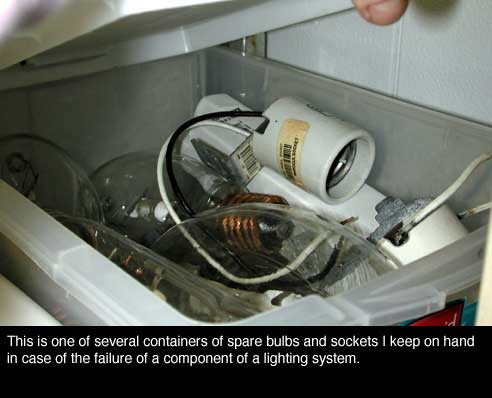

Lights

|

- I would keep at least enough

used bulbs, extra bulbs, or extra fixtures on

hand to provide a reasonable amount of light in

the event of bulb or ballast failure. Providing

light is less critical in the short term, but

I also realize that many times it takes longer

than expected to get replacements for specialty

aquarium fixtures, during which time the tank

can become unnecessarily compromised.

|

|

Heaters

|

- I am fortunate to live in

an area where heating tank water is rarely something

that needs to be done. However, I was reminded

by our editor that many poor souls live where

it physically hurts to go outside in the winter.

I don't know why anyone chooses to live where

eighteen layers of clothing must be worn, or where

it takes personal and city-wide effort to remove

snow and ice to walk or drive, but nonetheless

it seems they do. In such cases, reef aquaria

are under some threat from these elements, and

a back-up heater is an excellent plan to avoid

frozen fish and corals. In addition, heaters in

the aquarium hobby tend to be rather flimsy, in

particular the glass ones. I think the availability

of the titanium heaters in the trade, in addition

to inline heaters (expensive), are probably the

wisest puchase in terms of reliability and safety

to ones' tank and oneself.

|

|

Back-up Power

|

- There are many ways to provide

back-up power, and the subject has been written

about elsewhere (Trevor-Jones).

This is, however, the most critical piece

of emergency equipment. Among the many options

are generators, solar cells, UPC devices, battery

powered equipment, and car battery power inverters.

Included with any of these devices are the required

power strips and extension cords needed to get

power to the tank. It is not important to power

everything in the tank, but it is essential to

have a source of back-up power able to run at

least a main pump or enough powerheads to keep

the tank water circulating well.

|

|

Support Group

|

- Finally, making sure that

there are people available and within contact

to help or tend to an aquarium in the event of

a problem is literally a lifesaver. Aquarium clubs

provide ample opportunities to make such connections.

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

As is usually the case, I

finish an article only at a semi-random point or arbitrary

determination when I think I have written enough. There is

really no way to exhaustively cover all the little things

that are the product of years of experience. I find myself

concerned that through some omission here I will indirectly

cause the death of someone's livestock. I do sincerely hope

that the information here will be of use to those who have

not thought of such things, or have not yet had the opportunity

to do so. I also encourage others to visit my forum

on ReefKeeping to add their input and opinions to this

short "Insider's Guide" to Reef Aquaria.

|