|

This article represents the last part of

a three part series covering the many and widely variant sources

of reef fallacies and suppositions. As I mentioned at the

end of the last part in the series, the list I have made here

is by no means exhaustive, and one could practically continue

with such a listing for a very long time, and for a great

many words. I fully envision a whole new series of articles

as being possible within a relatively short period of time.

This is unfortunate, but stems largely from the fact that

reef keeping is still a relatively new practice, and there

are vast areas yet to be understood more completely.

It is fortunate that as the numbers of

aquarists increase, so do the number of significant findings

associated expressly with aquariums. Using information based

on the biology and ecology of natural communities, physical

and chemical canons, and general scientific bases is a strong

start. Yet, there are idiosyncrasies and specificities that

occur in aquariums that are unlike anything found in nature.

As such, more direct, careful, and judicious experimentation

will quickly lead to the elucidation of many of the artifacts

of closed system aquaria.

Myth 14: Microbubbles are to be avoided.

Many aquarists go to some considerable

lengths to baffle sumps and pump flows to prevent small bubbles

from being returned into the display tank. It has been suggested

that such bubbles represent an irritation to fish, corals

and other invertebrates and that they should be avoided. To

be honest, I am unsure from where the origin of this perception

came. However, it is untrue. Even the name is inaccurate…

the prefix "micro" would refer to bubbles too small

to see.

The onslaught of bubbles from this oncoming wave should make

it apparent that

corals and coral reefs exist just fine with

the presence of air bubbles in the water.

Small bubbles are very common in tumultuous

reef environments, and areas where waves break are often dense

with both reef life and small bubbles. In addition, in tanks

and on reefs, many bubbles of various sizes, including true

"microbubbles" are produced by photosynthesis, and

this is especially the case in highly illuminated environments.

In my own aquaria, a constant rise of bubbles, especially

in the afternoon, are produced by various corals and algae

in even some of my less-illuminated systems. Larger bubbles

frequently get sucked into pump intakes, and are chopped up

to even smaller sizes and distributed throughout the tank.

I won't even begin to discuss the massive numbers of bubbles

produced by various surge devices. These water motion devices

have great benefits in aquaria, and even as anecdotal aquarium

observations, I have never seen anything disturbed, irritated,

or harmed by the rush of bubbles.

Potential: Relatively harmless.

Neither bubbles nor the lack of them in a tank is likely to

endanger the health or survival of organisms.

Distribution: A patchy, but

common belief.

Myth 15: Concepts about Nitrification,

Stocking Orders, and the New Tank

I had owned Nilsen and Fossa's The Modern

Coral Reef Aquarium for several years before I noticed

one particular photo in that book that is exceptional. It

is a nice reef tank, but by no means what most would consider

to be a "show winner." However, it is unquestionably

a show winner, for it is a reef aquarium that grew solely

from live rock. If there is one universal answer to the question,

"What does it take to make a successful reef aquarium,"

the answer is patience.

For those who have not read one of the

threads stuck at the top of The Coral Forum, I offer this

revised version of that information. A tank begins without

populations of anything. Live rock typically forms the initial

basis of the biodiversity. Virtually everything is moderated

by bacteria and photosynthesis in our tanks. So live rock

is the substrate for these microbes and processes, and also

has a lot of other life on it. How much depends on a lot of

things. Mostly, marine animals and plants don't like to be

out of water for a day, much less the many days to sometimes

weeks that is common during live rock collection and shipping.

So, assuming that existing rock from a tank is not being used,

nor the well-treated aquacultured rock, most live rock is

either relatively free of anything alive, or has a few stragglers

and a whole lot of stuff dying or about to die because it

won't survive in aquariums. From the moment it is added to

the aquarium, a deficiency has begun that likely worsens over

time. Coralline algae, sponges, worms, crustaceans, echinoids,

bivalves, algae, chordates, and all manner of other taxa will

begin dying, many of which are within the rock and would never

be seen. All this occurs without mentioning the algae, cyanobacteria,

and bacteria, most of which is dead and will decompose, or

which will die and decompose. Life will return to some degree,

as we all have experienced, but not until death and more death

have occurred. However, this process is where it all begins.

Bacteria grow really fast, and so they

are able to grow to levels that are capable of taking up nitrogen

within a typical cycling time of a few weeks to a month (or

so) to levels where ammonium and nitrite are not measurable

by hobby test kits. Most people assume, wrongfully, that the

tank is now "cycled." However, the fact that ammonium

and nitrite are no longer easily measured does not in any

way imply that the tank is truly cycled, mature, stable, or

in any way able to easily support life in the form of new

additions. I will discuss this more in the passages below.

If one realizes the doubling time of many

bacteria, one would know that within a month, there should

exist a tank packed full of bacteria with no room for water.

That means something is killing or eating bacteria. It should

also be realized that if the tank has decomposition happening

at a rate high enough to spike ammonia off the scale of a

hobby test kit, there is a lot of food for bacteria that consume

this material, and far more than will be present when other

things stop dying off and decomposing. So, bacterial growth

may have caught up with the level of nitrogen being produced,

but things are still dying. An aquarist simply "tests

zero" for ammonia because there are enough bacteria present

to keep up with the nitrogen being released by the dying organisms.

It does not mean things are finished decomposing.

Now, if things are decomposing, they are

releasing more than ammonia. Guess what dead sponges release?

All of their sequestered toxic metabolites. Guess what else?

All their natural antibiotic compounds and these will prevent

some beneficial microbes from doing very well. The same occurs

with the algae, many other invertebrates, the cyanobacteria,

the dinoflagellates, and others. Suffice to say that this

death and decomposition is going to take a while to complete.

Through the initial periods, there will

be a tank packed with some kinds of bacteria, probably not

much of others. Eventually, the massive death slows and stops.

Now, what happens to all that biomass of bacteria without

a food source? They die. So, another cycle of decomposition

begins, and this back and forth process will continue for

a while until equilibrium is reached. I say equilibrium, but

that is a relative term since reproduction and mortality is

a constant process in our tanks, as are "mishaps"

and the relative size of the pendulum swing will depend on

the reproduction and mortality rates, and biomass of the organisms

involved. Still, the new swing of dying bacteria also has

antibiotics, toxins, and other substances released when they

die. But, the die-off is relatively slow, and is relative

to the loss of nutrients, and there is already a huge population

present. The result to the aquarist is that they never test

positive for significant levels of ammonia. "The water

tests fine."

Furthermore, denitrification is a slow

process. Yet, all these back and forth swings are happening...

every time, they get less and less, but they keep happening.

Eventually, they slow and stabilize. What's left? A tank with

limited denitrification and a whole lot of other stuff in

the water. Who comes to the rescue and thrives? The next fastest

growing groups... cyanobacteria, single-celled eukaryotic

algae, and other protists. Then, they do their little cycle

thing. And then come the turf algae. Turfs will soon get mowed

down by all the little amphipods that are suddenly springing

up because they have a food source and will reproduce rapidly.

Perhaps the aquarist has purchased some snails by now, and

maybe a fish. All too often, the fish dies, because while

it may not have ammonia to contend with, it has water filled

with chemicals we can't and don't test for. Beginning aquarists

may also have been too frugal with their purchase of important

equipment like lights and pumps, and may not have yet figured

out the important alkalinity test, so pH and O2

are probably swinging wildly at this point. Tests for phosphate

are also usually an afterthought, often purchased only when

algal biomass becomes uncontrolled.

|

No one wants their tank to look like this!

As a few more months pass, the algae successions

begin, and eventually there exists an algal biomass that handles

nitrogen along with the bacteria, and the aquarium keeper

has perhaps stopped adding fish for the time being because

they keep dying. Maybe during this time they started to visit

internet forums, read books, begin learning more, and get

the knack of the tank at least a little bit. They have, unfortunately,

probably added a smattering of "fix-it-quick" chemicals

(that probably didn't help any, either). Also, there are probably

two further scenarios; aquarists that are scared to add corals

in their "new tank of death" that would actually

help with the photosynthesis and nutrient uptake, or aquarists

that have packed in corals (most of which aren't tolerant

of the "tank of death" conditions). Equally common

are aquarists who stock their tank haphazardly without consideration

of whether or not the habitat present is suitable, but that

is a topic for another article. What may be relevant, however,

is the common pattern of stocking corals according to "hardiness"

over time. Initially, soft corals of the family Alcyoniidae

(leather corals), corallimorpharians (mushrooms) and zoanthids

are the first species to be purchased. The rationale for most

is that they plan to stock with easy corals and then "move

on to stony corals." The problem with the rationale,

seemingly logical though it may be, is that success of these

type species may make the tank even more incompatible for

the success of stony corals because they are typically superior

competitors (usually by secreting waterborne chemicals that

inhibit or kill the stony corals or by the capability of overgrowing

them).

|

A host of "fix-it-quick" products exist to help

new aquarists through early troubled times.

About a year into the experience, the sand

bed is productive and has stratified, water quality is relatively

stable, and the aquarist has probably bought at least a few

more powerheads, understands water quality a bit, some corals,

coralline algae and other algae are photosynthesizing well,

and the tank is becoming "mature." That's usually

when fish stop dying and corals start to live and grow.

Ecologically speaking, this is successional

population dynamics. Its normal, and it happens when there

is a hurricane or a fire or other disturbance. In nature though,

there are pioneer species that are eventually replaced by

variably persistent "climax" communities. We usually

try and stock tanks immediately with climax species and find

it doesn't always work. The preceding passages illustrate

what good approximations reef aquariums are of mini-ecosystems.

Processes and events tend to happen much faster in tanks,

but this should be expected given the number of organisms

per unit area. Our "climax community" happens in

a couple of years rather than a couple of centuries, but it

happens nonetheless.

After all the descriptions above, perhaps

the "myth" that is the focus of this article has

been forgotten. This section actually covers several myths:

the myth reflected by the statement "my tank is cycled"

or "my rock is cured," and the myth of the statement

"my water tests fine." The truth is that the tank

is never cycled, the rock is never cured, and water that "tests

fine" may be variably fine in terms of one or a few parameters

that may or may not be ultimately important for the survival

of the creatures we keep in aquaria. As a supplement to this

section, I offer some advice (and "advice" is not

something I am overly fond of providing because it tends to

be limiting to the viewpoint of the person giving it!). I

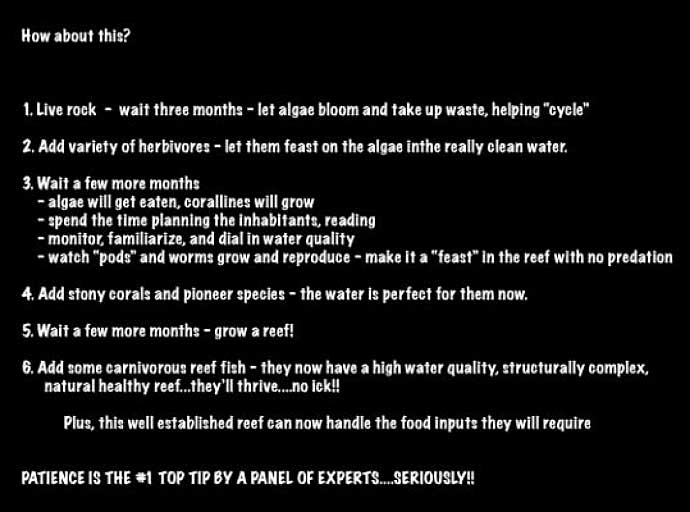

offer the words from a slide I have given in presentations

and am frequently requested to print or email after I have

shown that slide to a group. The following is how I would

suggest new tanks be initiated:

|

Potential: Always serious.

Mortalities early in the life of an aquarium can usually be

prevented. At the worst, these early misconceptions lead to

long-term problems with tanks, have medium-term direct effects,

and short-term mortality associated with them. Often, prevention

and understanding would alleviate the issues, and surely many

aquarists leave the hobby because of the many problems that

happen early on with new aquarium set-ups.

Distribution: Nearly universal.

Being patient with a new tank is almost an exercise in futility

that requires restraint. Generally, only those who have kept

reef aquariums prior to establishing a new one are likely

to take the steps required to ensure the best development

and success of new set-ups (and this is still comparatively

rare). Ultimately, the development of a tank by the actions

of an aquarist who "goes slow" will far outpace

those of aquarists who lack the patience and foresight.

|

Many

years down the road, another condition might occur when

the system is too mature; this is sometimes called "old

tank syndrome." What happens in this situation

is that conditions have become somewhat stagnant, or

populations that are present are either limited by some

resource or are the only species capable of persisting

in the relatively non-fluctuating environment. This

happens in nature, too. The well-known example of a

forest fire reinvigorating the system is true. Equally

true examples occur on coral reefs where the intermediate

disturbance hypothesis is an experimentally favored

explanation of why coral reefs maintain very high diversity;

they are stable, but not too stable; require storms,

but not catastrophic ones; need predation, but not a

giant blanket of crown of thorns starfish; tolerate

mortality, but not mass coral bleaching or the near

total loss of key herbivores.

|

Myth 16: Corals will regrow over

dead areas of their skeleton.

This one is only partially a myth. Living

coral tissue may indeed grow back over skeleton that has been

exposed from partial mortality of the colony. However, there

is no real reason to suspect it will, and unless there are

small bits of tissue still living inside the apparently dead

skeletal corallites, the process is not as it may appear if

exposed areas are eventually recovered by living tissue.

Coral skeletons form part of the reef framework.

Once they die, for whatever reason, the skeletons are eroded

and become encrusted by other life, including other corals.

With partial mortality, living parts of a colony have no "attachment"

to their old vacant corallites, figuratively or literally.

It is not a preferred place for them to live and grow. The

coral tissue that remains alive will simply keep growing and

calcifying, upwards and outwards. Whether or not it grows

outward and recovers its own dead skeleton is mostly a matter

of how favorable it is to grow in that direction. Generally,

at the rate corals grow, the exposed skeleton will have long

been covered with other organisms vying for space before the

coral can grow over it. To retake that skeleton means that

some sort of competition will be required. In some cases,

it may simply be overgrowing coralline algae. But, if it means

overgrowing more competitive organisms, the remaining colony

may just grow off in other more energetically favorable directions.

In fact, this is more than likely what would happen.

Even if the coral does recover its own

dead skeleton, the polyps that grow over it will not take

up residence in the old corallites. They will create their

own new ones on top of the old ones. This type of regrowth

can be used as a proxy of environmental events that caused

partial mortality to a colony, and cores taken from old colonies

usually show a change in the primary axis of growth when the

skeletal core is examined in cross section.

As I stated in my first article in this

magazine, partial mortality of a colony is nothing to be concerned

about, and whether or not it ever becomes recovered with the

same coral's tissue is not really a concern so long as the

remaining polyps of a colony continues their growth somehow.

After all, none of us are really too concerned about the appearance

of all the calcium carbonate that lies underneath the living

veneer of tissue, either. Time heals all wounds, even in coral

colonies.

Potential: Minimal in terms

of the health of the tank and the coral colony.

Distribution: patchy but

common statement and belief throughout aquarium circles.

Myth 17: You can never skim a tank

too much.

Yes, you can. Far too many works have dealt

with various aspects of protein skimming. I still feel there

is too little information on exactly what, how much, and how

effectively foam fractionation affects various components

of the water column of reef aquaria. For the most part, protein

skimmers are employed as water quality control devices to

maintain low levels of organic and some inorganic materials,

notably compounds containing nitrogen and phosphorous commonly

linked to degraded water quality not conducive to the growth

of many reef species such as corals. Whether or not they are

used secondarily for other questionably useful purposes such

as elimination of toxins or increasing oxygenation is another

matter. My point is that once nutrient levels are low and

conducive to a healthy aquarium, and until other secondarily

important aspects of protein skimming are experimentally validated

and quantified, any skimming over that required to maintain

low levels of organic and inorganic pollutants is overskimming.

Why? Because if the water is cleared of those things that

are detrimental, it is also likely to be equally cleared of

things that are beneficial. Given the now well-recognized

limitations of providing large amounts of food without a corresponding

decrease in water quality, skimming as little as possible

while maintaining the aforementioned high water quality is

only pragmatic. There is no advantage to a constantly stripped

water column in all but a very few specialized situations.

If I were asked what a solution might be,

I would propose the following. Use the most efficient skimmer

possible and one that is capable of maintaining high water

quality when used constantly. Assuming that they do provide

some amount of oxygenation, even if minimal, I would then

begin shutting off the skimmer during the day for a few hours

and measure tank condition visually and through testing for

several weeks. If water quality is maintained, I would increase

the number of hours the skimmer is off, and wait again, continuing

this process until the maximum number of hours is reached

where water quality and tank health remains the same without

the use of the skimmer. I would also opt for daylight discontinuance

since oxygen is less of a problem when photosynthesis is occurring,

and since most aquarists tend to feed fish and other products

like phytoplankton during the day. This way, residual foods

will not be removed for at least several hours. Some aquarists

may even find that they can discontinue skimmer usage entirely

(I think this likely, especially if activated carbon is employed).

Potential: Minimal to serious.

In the best cases, continuous skimming results in relatively

healthy tanks that are considered successful by most standards.

In the worst cases, organisms perish because of the lack of

available foods in the water column. In most cases, the results

are a "sterile" looking tank with little alive but

corals and coralline algae. Corals tend to appear weakened

and, for lack of a more accurate description, not robust.

Distribution: Extremely widespread.

There are many who employ alternate means of tank filtration,

and these are usually the same people who appreciate the obvious

differences in allowing more material to remain in the water

column without compromising water quality. Foam fractionation

use is both desirable and extremely widely employed, but as

with other things should be employed properly and with a judicious

purpose.

Myth 18: My aquarium is a reef-crest

type tank.

Sorry, but I very much doubt it. There

are many reef crests that are occasionally exposed to widely

variant conditions that range from onslaughts of rushing water

to absolute stillness. But, the typical fringing coastal,

atoll, or barrier reef crest is someplace humans don't usually

go or can't negotiate. Why? Because of the imminent threat

of serious personal injury. It only takes a very small wave

breaking over shallow corals to toss a human of considerable

weight like a leaf in the breeze. If one snorkels near a reef

crest, it is a constant physical negotiation to keep from

being smashed onto rocks and coral. A continuous body adjustment

as one is lifted up and down and side to side, consisting

of dexterous twists and brief sprints, is required to be in

this area. Even fish adjust their swimming behavior. As waves

approach and cross an area, small fish trying to maintain

their position or territory swim as hard as they can in one

direction, only to quickly stop as the wave passes. Other

fish take shelter in corals and rocks each time a wave passes.

While not on the reef crest, nearby stiff-bodied invertebrates

strain against the water forces, bent sideways every few seconds.

Softer bodied creatures, only existing in more protected nooks

alee of wave action are pummeled, and it amazes and fascinates

me that they survive the continuous unrelenting barrage of

wave action. On the reef crest itself, it is very unlikely

soft bodied sessile animals will exist. It is a very stressful,

violent, inhospitable and relentlessly tiring place to live.

Many aquarists think of reef crests as

being areas where many species of Acropora and small

polyped corals are found. In fact, only some species are found

there and the greatest diversity exists quite a bit deeper.

Staghorn corals are not found on most reef crests because

they would be shattered. Table corals are not found on reef

crests. They would be uprooted. Only the most robust growth

forms exist there, and colonies tend to be small. On many

reef crests, the force of water and the particles in it are

too erosive and abrasive to allow for any soft tissues to

exist, and corals are excluded. In such places, coralline

algae and perhaps encrusting Millepora are providing

the cover of the reef crest.

I have never seen a home aquarium where

I would feel physically in danger were I able to get inside

of it. I have never seen a pump that would toss me around

like a leaf. I have never seen any tank anywhere that in anyway

resembles a reef crest. Even small crafts with outboard engines

have difficulty maintaining a position anywhere near a reef

crest, and I suspect no one has an aquarium that would thwart

a 40 horsepower Johnson outboard. To provide conditions even

like those at five to ten meters depth in an aquarium would

still be quite a feat.

Potential: Minimal to serious.

In most cases, this myth is just a misconception of the nature

of both the reef crest and the tank. It won't do much harm.

However, if one perceives their aquarium to be a reasonable

facsimile of a reef crest and attempts to maintain animals

found on or collected from a reef crest, failure might be

the result.

Distribution: Fairly common,

especially among non-divers and enthusiasts of small-polyped

corals.

Myth 19: To propagate corals, one

should break or cut off a branch or section, and then apply

glue or affix the broken fragment to new substrate.

Coral propagation is really quite easy.

But, as I have said many times, these are not plants. Perhaps

the use of terms like "stalks" and "branches"

and "photosynthesis" confer this notion. But, one

should not "plant" corals with the healthy parts

up and the broken edge in the dirt, as though this was the

"root area."

The goal in propagation is rapid attachment

with low mortality. Broken tissue is an injury, and injuries

are more prone to get infected. Reef substrate is covered

in biofilms and other microbes. The substrate also has reduced

oxygen and water flow, and is a site where other organisms

may engage in competitive or predatory behaviors. Finally,

injured tissue must undergo repair before growth is initiated.

The only helpful attribute of the "coral planting"

method is that the tissue edges are often sealed by cyanoacrylate

(super glue) that minimizes chances of infection. Epoxy putty,

however, confers much less of an advantage since the glue

is much less adhesive to mucus-covered tissue unless very

diligently applied.

Providing the maximal amount of healthy

tissue against substrate encourages rapid attachment and reduces

the chances of infection and mortality. Placing cut edges

in water flow encourages healing and reduces the effects of

the detrimental attributes of substrate. Try it. I suspect

all the little "pine seedling" propagators out there

will soon change their ways.

The photo above left shows the "wrong way" to mount

corals. The photo above right shows the right way to mount

corals.

Potential: relatively minimal.

Corals are tolerant animals, in general, to fragmentation

and the majority of fragments even affixed in the wrong way

by "planting them" will probably survive. Some that

do not survive may have survived if affixed by a different

method more conducive to regeneration. The biggest potential

detriment is the increase in the time it takes for fragments

to reattach and in reduced growth potential.

Distribution: Extremely widespread.

Almost everyone, including those who propagate corals "professionally"

are mounting corals incorrectly.

Myth 20: The aquarium hobby has little

to no impact on reefs.

In some cases this is true, in some cases

this is untrue, and in most cases we just don't know what

our impact is. But, in some cases the aquarium trade has caused

significant declines in targeted species. The solution is

to be aware of what wild collected species are common, and

which are not, and to always purchase sustainably collected,

maricultured, or aquacultured stock when possible. I look

forward to covering this topic in much greater detail in a

future article.

Potential: Devastating to

some species, of minimal concern for others.

Distribution: This is a widespread

conception that is unfortunately based largely on supposition

and the hope that the statement is actually true.

Summary

This series has been a very incomplete

look at some of the more pervasive myths that are part of

the community of people keeping marine and reef aquaria. In

the first part of the series, I began with a somewhat lengthy

discussion of critical thinking and definitions of terms like

"anecdote."

Being skeptical and critical in our assessment

of information in this hobby is imperative. The facts are

few, the opinions are many. The general level of understanding

is low, the data to support our observations scant, and what

persists is the all-to-common willingness to support our own

shortcomings of knowledge with those spoken and written by

those equally or sometimes more in the dark than ourselves.

We must listen more, think more, read more,

and speak less. At the very least, we should temper our enthusiasm

and excitement by prefacing our supposed truisms with really

helpful modifiers; could, should, might, probably, seems to,

in my observations, in my opinion, and looks like will more

credibly explain the immense number of unknown possibilities

that express themselves regularly to us through the windows

of our tanks. In time, we might even be able to say assuredly

"my water tests fine" and quantify how "my

tank never looked better."

Link to

Part

One, Part

Two

|