|

Actually, both are correct. The word "cteno"

means "comb" and "chaetus" means

"bristle." Put the two together and you get Ctenochaetus,

the name given to a small genus of surgeonfish that many consider

the best herbivore for filamentous algae in home aquariums.

They are moderately attractive, non-aggressive, grow smaller

than most Acanthurids, and are not as active as some of their

cousins. With all of these positive factors it would be hard

to go wrong in purchasing one, right? In the words of Lee

Corso, "not so fast my friend." For the July issue

of Reefkeeping and "Fish Tales" I'll dive

into the genus commonly referred to as Bristletooth or Combtooth

Tangs.

Meet the Family

As Surgeonfish, all Bristletooth tangs

can be found in the family Acanthuridae. This family consists

of three sub-families, six genera, and seventy-two species

(Michael, 1998). All species possess at least one, and possibly

three or more, potent weapons just forward of the base of

the tail, on an area known as the caudal peduncle. This weapon

is similar to a dagger and consists of modified scales. Extensive

tests have been inconclusive in showing any sort of venom

associated with this knife-like spine, but it is important

to note that in one series of observations, every fish cut

with the dagger of modified scales from members of the sub-family

Prionurinae have died as a result of the wound (Baensch, 1994).

Luckily, fish from the sub-family Prionurinae rarely make

it into the hobby. Ichthyologists use the caudal peduncle

as a distinguishing character to place each member into one

of the three sub-families. In all three sub-families the dagger

is attached closest to the base of the tail, and extends toward

the front of the fish. Having only one spine in the caudal

peduncle, all Ctenochaetus species are placed in the

sub-family Acanthurinae.

|

Sub-families:

|

Genera:

|

| Acanthurinae |

Acanthurus |

| |

Ctenochaetus |

| |

Paracanthurus |

| |

Zebrasoma |

| Nasinae |

Naso |

| Prionurinae |

Prionurus |

Ctenochaetus contains nine species

(see below), all found in the tropical Indo-Pacific. All nine

members of the genus have an unusual mouth and teeth structure.

Adults can have more than 30 teeth per jaw, and all are flexible

and slender and are described as having "expanded, incurved,

denticulate tips" (Randall and Clements, 2001) (more

on teeth later). Another notable characteristic in Ctenochaetus,

distinguishing them from other Acanthuridae, is the total

number of dorsal spines. Whereas most Acanthuridae possess

nine dorsal spines, Ctenochaetus only has eight. Similar

to most Acanthuridae, Ctenochaetids possess a very long intestine

which functions similar to a stomach, making up for the inefficient

gizzard-like stomach of the surgeonfish.

| §binotatus |

| §cyanocheilus |

| §flavicauda |

| §hawaiiensis |

| §marginatus |

| §striatus |

| §strigosus |

| §tominiensis |

| §truncatus |

|

|

Members of the genus Ctenochaetus

were discovered as long ago as 1825, but at that time they

were placed in the genus Acanthurus. In 1831 Bonaparte

erected Ctenodon, which wasn't validated until Klunzinger

(1871). Finally, in 1885, Gill changed Acanthurus strigosus

to the newly erected genus Ctenochaetus. It remained

a slow transition, however, with Ctenochaetus remaining

a small genus of only two specimens until 1955 when Randall

decided a revision was in order. In doing so, he named five

new species to bring the total to seven recognized Bristletooth

tangs. More recently, Randall has done a second revision,

in which he named two additional species, bringing the total

number of Ctenochaetus to nine.

There is a group of four Ctenochaetus

that are classified as variants of Ctenochaetus strigosus

(Randall, 1955). In 1955, Randall was tempted to opt for sub-species

status, but choose to classify them as the Ctenochaetus

strigosus complex instead. These four varieties of fish

are extremely similar. They differ by slight coloration variations

and from the locale in which they originate. Gill raker counts

and dorsal soft rays also vary slightly. Additional DNA research

is ongoing and should prove invaluable in sorting out confusions

such as the C. strigosus complex.

Ctenochaetus strigosus

allopatric species

|

Species

|

Variation

|

Location

|

| C.

strigosus |

Yellow

encircles the eye. |

Hawaiian

Islands |

| C.

cyanocheilus |

Dark

overall, with slight white coloring on tail. |

Central

Pacific Ocean |

| C.

flavicauda |

Pure

white caudal peduncle and fin. |

Eastern

South Pacific |

| C.

truncatus |

Blue/yellow

dots; truncate caudal fin. |

Indian

Ocean |

In the Wild

All Ctenochaetus species are found

in the tropical Indo-Pacific. Species can be found as far

west as the East coast of Africa (C. truncatus, C.

binotatus, C. striatus), and as far east as Panama

and Columbia (C. marginatus). Likewise, distribution

extends from as far south as New South Wales (C. binotatus)

up to Southern Japan (C. cyanocheilus). Most species

are found in less than 100 feet of water, usually occurring

in 50 feet or less. However, C. strigosus has been

reported to occur as deep as 340 feet (Randall and Clements,

2001). They prefer reef walls or steep slopes, which are often

pounded by stiff currents and clean, highly oxygenated water.

This juvenile coloration is tough to differentiate from other

possible juvenile color forms. This one

appears to be C. truncatus, but C. strigosus

is nearly identical. Once the adult color form begins

to shine through it will make identfication much easier. Photo

courtesy of Greg Rothschild

of Mother

Nature's Creations.

Although the fish in family Acanthuridae,

and subsequently the genus Ctenochaetus, are often

viewed upon as strict herbivores, this is hardly the case.

In contrast to popular belief, these unique teeth of Ctenochaetus

are not designed for consuming algae whatsoever. The teeth

are geared for rasping fine detrital material from rocks and

sand while the carp-like design of the mouth is efficient

at sucking up this detrital material. This detrital material

consists of diatoms, various small fragments of algae, large

amounts of unidentifiable organic material (as much as 90%

of one fish's stomach contents) and fine inorganic sediment

(Randall, 2001).

Juvenile Bristletooth tangs are likely

to remain in loose aggregations. They also have a specific

juvenile coloration, which gradually changes to the adult

coloration when they reach lengths around 7 or 8 cm. This

juvenile coloration is oftentimes a vibrant yellow, orange,

and blue, whereas the adults tend to manifest drab browns,

creams, and blacks. Adults generally maintain pair bonds,

except for C. strigosus, which is a solitary adult,

and are virtually identical looking. There are no external

variations to differentiate sexes; however, it has been noted

that the larger of the two will be the male (Robertson, 1985)

and in at least a few species sexual dichromatism is present

during courtship (Randall, 1961). In at least one species,

C. striatus, adults gather during the lunar cycle to

mate in small harems (Randall, 1961 and Robertson, 1983).

However, the fish in the C. strigosus complex have

been noted as spawning only in pairs (Baensch, 1994).

|

An adult C. binotatus is seen here. The juvenile color

form will have a bright yellow

tail and lack the spots that cover the adult. Photo courtesy

of Greg Rothschild of

Mother

Nature's Creations.

As can be expected with any fish that consume

dinoflagellates, Combtooth tangs have been reported in Ciguatera

poisoning events. In fact, this fish contains two toxins.

One is a fat-soluble toxin and the other is a water-soluble

toxin. Chromatography was used to prove the fat-soluble toxin

as ciguatoxin (Yasumoto et al. 1971). For those unfamiliar,

Ciguatera poisoning is usually associated with bottom-dwelling

shore reef fish; it the most common fish-borne seafood intoxication.

These fish feed on toxic dinoflagellates and the causative

agent, ciguatoxin, becomes concentrated in the meat of these

fish. Humans eat the meat, and the ensuing sickness is called

Ciguatera poisoning. The water-soluble toxin, which is located

in the liver, was later discovered to be maitotoxin. For those

not familiar with maitotoxin, it is contracted much the same

way as Ciguatera poisoning, but it increases the calcium ion

influx through excitable membranes such as those surrounding

nerve or muscle cells; this is not affected by tetrodotoxin

or sodium. Such a calcium influx can result in rapid death.

These substances are some of the most lethal natural substances

known. In mice, ciguatoxin is lethal at 0.45 ug/kg ip, and

maitotoxin at a dose of 0.15 ug/kg ip. Oral intake of as little

as 0.1 ug ciguatoxin can cause illness in the human adult

(as an extrapolation from fish samples eaten) (NIEHS

Marine and Freshwater Biomedical Sciences Center). So…

don't eat your Bristletooth!

In the Home Aquarium

Provided the hobbyist meets a few basic

requirements, captive care of Ctenochaetus species is quite

possible. The first step into a positive experience with these

fish is selecting a healthy specimen. Oftentimes Bristletooth

surgeonfish arrive at the local fish stores with damaged fins,

or more likely, a damaged mouth. Close inspection by the hobbyist

is encouraged. Avoid any fish with obvious signs of damage.

Likewise, ensure the fish is eating. The vast majority of

the diet should be obtained from grazing upon the natural

growing algae and detrital material of the aquarium. Although

in the wild the vast majority of its diet is detritus, in

the home aquarium it tends to accept larger amounts of algae

to compensate for the lack of enough detritus. However, supplemental

feedings of most any of the commercially available algal-based

foods is encouraged. I would also recommend supplemental vitamin

additions to the prepared foods. If the fish passes visual

inspection, is seen grazing on the rockwork and sand of the

aquarium, and feeds upon prepared foods, it is likely a good

candidate for purchase.

|

The juvenile color form of C. hawaiiensis is often

regarded as the most

attractive Bristletooth Tang. Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild

of Mother

Nature's Creations.

The next consideration before purchase

will obviously have to deal with the aquarium setup itself.

A large amount of live rock is essential to the well-being

of Ctenochaetus surgeonfish. I highly recommend that

you not place these fish into aquariums that are lacking live

rock and live sand. These aquariums are often too sterile

for Bristletooth surgeonfish and oftentimes the fish will

develop mild to severe cases of Head and Lateral Line Erosion.

When provided with a large amount of live rock, a sand bed

and several glass sides of the aquarium that remain untouched

by the hobbyist, these fish can do quite well, since all of

these surfaces will be utilized for grazing by the surgeonfish.

Of course the on-going debate over aquarium

size and surgeonfish is a hotly debated on message boards

across the 'net. Though it seems no one can agree on minimum

aquarium size, it does seem everyone can agree the larger

an aquarium is, the more natural personality a fish is likely

to exhibit. Ctenochaetus species are often referred

to as the surgeonfish best suited for smaller aquariums, with

many proponents citing a minimum four-foot long aquarium.

I feel the average four-foot long aquarium is likely to not

meet all the objectives for a healthy environment for this

fish. The objectives that need to be met are ample swimming

room, and ample rockwork and sandbed for grazing, and pristine

water conditions. In order to meet one objective, you would

be likely to fail in another. For example, if you wanted to

have optimum swimming space for the fish, you'd likely fall

short on available grazing opportunities on the live rock.

However, if the minimal amount of live rock produces enough

food, it is likely your water parameters are less than optimum.

Larger amounts of live rock will reduce swimming areas, as

well as water circulation.

Naturally, I expect your current thoughts

to be looking for that "magic number" of gallons

or inches that will ensure proper husbandry of Bristletooth

tangs. I will hesitate in supplying that magic number but

instead opt to remind you of Choat and Axe (1996) and their

study regarding several Acanthurid fish and growth patterns.

Following Choat and Axe and the understanding that Acanthurids

obtain 80% of their growth in their first 15% of life, an

idea of how fast they should be growing in your aquarium can

be calculated. Combine this with an expected 35 years of age

per Acanthurid (Chaot and Axe, 1996), we come up with 80%

growth obtained in 5.25 years. For the larger Ctenochaetus

species that equals roughly seven or eight inches of length.

It is unlikely that a four-foot long aquarium will provide

a suitable environment to match these natural growth patterns.

|

This C. binotatus is nearly a full adult color pattern.

Note the yellow tail still remaining

from the juvenile color form. Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild

of Mother

Nature's Creations.

With the aquarium requirements already

discussed, I can now focus on tank mates. Generally speaking,

Bristletooth tangs will ignore most any other fish in the

aquarium. In most cases the only exception to this rule are

other Acanthurids. Even so, the problem therein lies with

the other surgeonfish harassing the Bristletooth, not the

other way around. If a second Acanthurid is to be mixed in

the same aquarium with Ctenochaetus, it is recommended

the Bristletooth be well adjusted to the aquarium prior to

addition of the second surgeonfish. Mixing two Ctenochaetus

is probably best avoided unless a pair is obtained. As far

as surgeonfish are concerned, Ctenochaetus species

are mild mannered and can become bullied by larger or more

dominant animals. Therefore, obviously, it is best to avoid

anything that may harass this surgeonfish. Their mild manners

extend to not only other fish, but also with invertebrates.

Bristletooth tangs should be considered safe with all corals.

Compatibility

chart for Ctenochaetus:

|

Fish

|

Will Co-Exist

|

May Co-Exist

|

Will Not Co-Exist

|

Notes

|

|

Angels, Dwarf

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Angels, Large

|

X

|

|

|

Tang in first.

|

|

Anthias

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Assessors

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Basses

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Batfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Blennies

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Boxfishes

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Butterflies

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Cardinals

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Catfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Comet

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Cowfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Damsels

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Dottybacks

|

|

X

|

|

Some Dottybacks require dedicated aquariums.

|

|

Dragonets

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Drums

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Eels

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Filefish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Frogfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Goatfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Gobies

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Grammas

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Groupers

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Hamlets

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Hawkfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Jawfish

|

X

|

|

|

Jawfish in first.

|

|

Lionfish

|

|

X

|

|

Should co-exist fine, but large lions may consume juvenile

tangs

|

|

Parrotfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Pineapple Fish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Pipefish

|

|

|

X

|

Pipefish require dedicated aquariums.

|

|

Puffers

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Rabbitfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Sand Perches

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Scorpionfish

|

|

X

|

|

Same as Lionfish.

|

|

Seahorses

|

|

|

X

|

Seahorses require dedicated aquariums.

|

|

Snappers

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Soapfishes

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Soldierfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Spinecheeks

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Squirrelfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Surgeonfish

|

|

X

|

|

Bristletooth in first.

|

|

Sweetlips

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Tilefish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Toadfish

|

|

X

|

|

May consume juvenile tangs.

|

|

Triggerfish

|

|

X

|

|

Some Triggerfish require dedicated aquariums.

|

|

Waspfish

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

|

Wrasses

|

X

|

|

|

Should be excellent tank mates.

|

Note: While many of the fish listed are

good tank mates for Ctenochaetus species, you should

research each fish individually before adding it to your aquarium.

Some of the fish mentioned are better left in the ocean, or

for advanced aquarists.

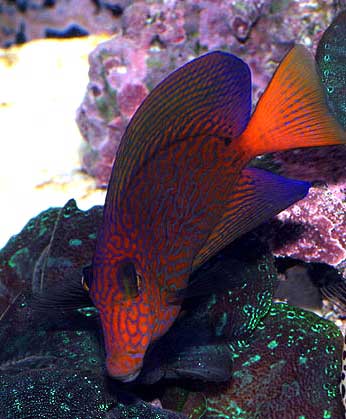

The striking color pattern of the juvenile C. hawaiiensis

fades to a deep green horizontally

striped fish that appears

nealy entirely black until viewed from up close. Photo courtesy

of

Greg Rothschild

of Mother

Nature's Creations.

Meet the Species

Of the nine species of Ctenochaetus,

very few show up with any regularity in the ornamental fish

trade. Two species in particular, C. strigosus and

C. hawaiiensis, are by far the overwhelming favorites.

C. strigosus is slightly more available and definitely

more affordable, most likely due to the shallow depths they

can be found in as opposed to the 50 feet or deeper which

C. hawaiiensis typically inhabits. The solitary adults

associate with areas of dense algae growth. The Kole Tang,

as it is commonly called in the hobby, is endemic to the Hawaiian

Islands and happens to be one of the most common shore fish

of the islands. Juveniles are almost entirely lemon yellow

with a slight metallic blue trim along the edges of the dorsal

and anal fins. As the juvenile matures into an adult, it loses

all of the yellow except for a small portion that encircles

each eye. Once the yellow is gone the body takes on a shade

of rusty red to brown with blue spots or stripes flanking

the body.

|

The adult C. strigosus has a striking yellow patch

encircling the eyes. Juveniles are

lacking this yellow mark, as well as the white spots and stripes.

Instead, they are nearly

identical to the coloration of a juvenile C. truncatus.

Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild

of Mother

Nature's Creations.

Ctenochaetus strigosus seen here swimming in a home

aquarium. Photos courtesy

of Ken Hahn.

Ctenochaetus hawaiiensis, or the

Chevron Tang, is often considered the most attractive of the

Bristletooth surgeonfish. The juvenile is a striking orange

and blue combination. As the fish matures, the blue and orange

give way to an overall black appearance. Upon closer inspection,

dark green stripes will be found running through the black.

This fish was once thought to be endemic to the Hawaiian Islands,

but it is now known to inhabit a much larger territory stretching

from Guam to Pitcairn. It remains most numerous in the Hawaiian

Island chain, however, and all specimens showing up for retail

in the United States have been harvested in Hawaiian waters.

This is one of the larger Ctenochaetus species and

can be expected to reach nine or ten inches when provided

a suitable environment.

|

This photo (above) of C. hawaiiensis was taken

when the fish was likely 40mm in total length.

At this age the purple is intense. Photo courtesy of Nico

Tao (NKT). As the fish ages (below)

the purple begins to lose its intensity and the black lines

on the body begin to fade away. This

picture was probably taken near 75mm of total length. Photos

courtesy of Otto Bobis (ABahn).

The only Ctenochaetus species known

from the Red Sea is C. striatus. In the hobby these

fish are commonly called the Striped Bristletooth. Despite

a wide distribution throughout all of the Indo-Pacific except

for Hawaii, Easter, and Marquesas Islands, they are not regular

imports for the hobby. For the price C. hawaiiensis

is likely a better option. It is similar in size to C.

striatus, if not a little bit smaller.

The most aggressive Ctenochaetus

is C. tominiensis, or the Tomini Bristletooth. Originally,

this fish was thought to be endemic to the Gulf of Tomini,

but it is now known to be widespread throughout the Central

Pacific, even though it remains fairly rare in those locations.

In the home aquarium this Combtooth can be expected to harass

less aggressive fish. It has virtually little, if any, color

change associated with maturing from juvenile to adult, and

it is a very small surgeonfish, growing only to roughly five

inches.

Conclusion

Although Combtooth tangs are among the

smallest surgeonfish and the least active surgeonfish, they

still require large amounts of naturally growing food. Small

aquariums will likely not be able to keep up with their food

requirements. Although they are often thought to be strict

herbivores, it is obvious from stomach content analysis that

this is not the case, with algae making up only a small portion

of their diet. Meeting the dietary requirements for these

fish is a very important first step to their long-term success

in aquaria.

|