|

Like many aquarists, I have spent hours

on end watching my aquarium. The diversity of animals living

in the glass box in my living room is a constant source of

amazement for me. For the first two years I had a reef tank,

it seemed I could find a new critter each and every time I

spent more than five minutes looking. I've also spent hours

with a magnifying glass examining the smaller animals that

live on the rocks and in the substrate near the glass. These

magnified examinations showed me a whole new range of animals

that had previously escaped my notice. Even with all the animals

I had found with my own eyes and a magnifying glass, I was

still shocked at the number and variety of fascinating animals

living in my system that could only be seen and appreciated

through a microscope.

Microscopes range in price from $20 children's

toys to $75,000+ research lab equipment. I bought my first

microscope the same way I purchased my first digital camera.

I did some research over the web and learned about the basic

types of equipment and price ranges. I eliminated both the

toy scopes (knowing they would be useless) and the high-end

scopes (knowing they would be overkill). I wanted my first

microscope to be a moderately priced piece of equipment that

was good enough to give me an idea of whether or not I would

enjoy microscopy without breaking the bank. (Pretty much the

same way I took up reef keeping: I started with a thirty-gallon

acrylic tank and upgraded to my current setup after I was

sure that I liked being an aquarist.) In the case of the microscope,

my first purchase was a National model 138 (which was listed

as a high school level scope) that I bought online for about

$250.

Microscopes, like any good camera, are

all about the quality of the optics. Obviously, the quality

of the image from a $250 microscope is not in the same league

with a microscope costing $2,500 or more. While my $250 microscope

would not be appropriate for someone who had to spend hours

on end staring into it, for casual use in a hobby situation

it has been ideal. I've been using my National scope for three

years now and I've had lots of fun and learned more than I

could have imagined. The following are some of the photographs

I have taken through the eyepiece of my microscope using a

digital camera.

|

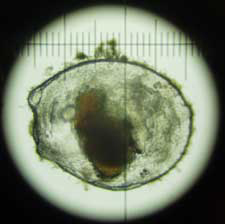

Foraminiferan test-

This calcium carbonate shell enclosed a single celled

amoeba which extended slender pseudopods from the

pores in the shell. These shells look like delicate

works of art through the microscope.

|

|

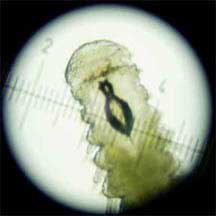

Harpacticoid copepod-

The single red eye helps identify this animal as

a copepod. The first time I saw one of these, I

was reminded of a trilobite.

|

|

|

Hydrozoan jellyfish-

This little guy is smaller than the period at the

end of this sentence. It was fun to watch him pulsing

around in the Petri dish. He is photographed against

strands of Bryopsis.

|

|

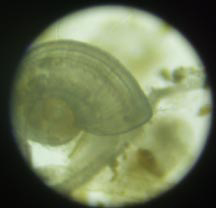

Bivalve-

The transparent shell allows you to clearly see

the internal organs of this bivalve.

|

|

|

Polychaete worm-

This closeup of a transparent polychaete worm shows

the jaw structure that resembles pliers. I could

watch this worm exert the jaws, grab a food particle

and pull it back inside.

|

|

Rotifer-

The name means "wheel-bearer" and after

seeing a live one under the microscope you know

why. These animals have what look like spinning

wheels on their head that create a water current

that draws food particles into the mouth.

|

|

|

A. percula larvae-

You can clearly see the yolk sacs and eyes on these

eight day old clownfish larvae. They are still encased

in their transparent egg shells.

|

|

Hydroid-

I found quite a large population of these tiny hydroids

living on the walls of my sump along with sponges.

|

|

|

Mite-

This is a true relative of terrestrial spiders that

I found in the debris at the bottom of my sump.

After seeing the number of animals living in my

sump debris, I no longer "clean" my sump!

|

|

Snail-

I frequently find empty shells from this type of

snail when I examine substrate from my tanks.

|

|

|

Pocillopora polyp-

This 30X magnification of a Pocillopora polyp

shows the round white acrospheres at the end of

each tentacle.

|

|

Pocillopora acrosphere-

One acrosphere flattened beneath a cover slip shows

hundreds of nematocysts. The golden brown objects

are zooxanthallae.

|

|

If you have been considering the purchase

of a microscope to get yourself started in this fascinating

world of discovery, here are just a few of the basics.

High-Power vs. Low-Power:

The two basic types of microscopes are

high-power and low-power.

High-power microscopes generally have three

to four distinct magnifications: 40X, 100X, 400X and sometimes

1000X. High-power scopes are used to look at very small things

such as single cells or bacteria that are mounted on a microscope

slide. Microscope slides are pieces of clear glass approx.

75mm long, 25mm wide and 1mm thick (3"x1") and are

generally used with cover slips. Cover slips are pieces of

glass approx. 22mm square and .17mm thick. (Cover slips are

VERY thin and VERY easy to break!) For a simple "wet

mount", a drop of water is placed on the slide and a

cover slip is placed over the top of the drop. The slide is

then placed on the stage for viewing. Since the lighting on

the high power scope comes from below the specimen, the specimen

needs to be transparent. (Fortunately, most of the very small

animals are, for the most part, transparent.)

Low-power microscopes (also called dissection

or stereo microscopes) are used to look at larger objects,

such as grains of sand or small animals such as brine shrimp

or small starfish. (By the way, they're also handy for checking

the settings on your jewelry or removing splinters from your

fingers!) The specimen is placed in a Petri dish (shallow

glass dish about four inches across) that allows the aquarist

to observe the animal moving around in the water. My low-power

scope has lights above the specimen and below that can be

independently operated, so the specimen can be illuminated,

even if it is opaque. The dual objective lenses produce a

three-dimensional image. These scopes come in a variety of

powers from 10x to 80x, with the most common being combinations

of 10x/35x and 20x/40x.

I own one microscope of each type. If I

my budget had only allowed for one microscope, I would have

chosen the low-power microscope. I frequently fill a Petri

dish with macro algae and substrate from the tank, refugium

or sump and hunt for new critters while watching the isopods,

worms, copepods, nematodes and myriad other animals go about

their business. I also have examined small starfish, brittle

stars, snails, coral fragments and whatever else I could catch,

under the low-power scope. It is amazing to be able to see

the detail of these small animals. I also use the low-power

microscope to find specimens that I want to examine further

under the high-power microscope.

The high-power microscope has been great

for examining small living animals like ciliates and protozoan

as well as coral cells and structures such as nematocysts.

A drop of water and small bit of algae in a depression slide

can contain dozens of single-celled animals swimming around.

(Unlike regular microscope slides that are flat glass, a depression

slide has a circular depression in the center that will hold

several drops of water. Cover slips are generally not used

with depression slides.) I have snipped off tentacle tips

from various corals (Plerogyra, Catalaphyllia,

Pavona) and compared the size and structure of the

nematocysts. A ground up tentacle from an Aiptasia

is ideal for studying zooxanthallae. (Finally, a good use

for Aiptasia!)

Binocular vs. Monocular:

Binocular microscopes have two eyepieces

for viewing. Monoculars have one eyepiece. Binocular scopes

are much easier on your eyes for extended viewing sessions,

but they are more expensive.

Extras:

Supplies - Items

such as microscope slides, cover slips, Petri dishes and basic

dissecting kits (which contain necessary tools like tweezers,

small scissors and probes) can all be found and ordered online.

Mechanical stage - The stage

is the flat surface where microscope slides are placed for

viewing. The least expensive microscopes will simply have

two clips to hold the slide in place. I highly recommend upgrading

to a mechanical stage for a high-power microscope. A mechanical

stage has a spring-loaded arm to hold the slide, and two knobs

to position the slide. One knob moves the slide right and

left and the other moves the slide up and down. Many of the

small critters I have examined move around quickly in their

drop of water and the mechanical stage allows me to move the

slide smoothly to keep up with them.

|

Carrying case

- A plastic carrying case with foam insert for storing

the microscope when not in use will help to insure that

your microscope does not get damaged.

Reticle

- Is a special eyepiece that has an inscribed scale

(right) that allows you to measure the specimens

you are viewing.

|

|

Photography:

The pictures that I took in

this article were shot using an Olympus E-100 digital camera

mounted to a tripod with the front lens of the camera directly

against the eyepiece of the microscope. This system works

for me because the viewfinder of my digital camera has through

the lens metering and a pretty good zoom lens. I look through

the camera, into the microscope and use the focus on the microscope

to adjust the fine focus on the image I am photographing.

The major drawback of photographing in this manner is that

I am not able to capture the entire microscope image in the

camera. I get a narrower field of vision through the camera.

This means that sometimes I have to switch down to a lower

magnification lens in order to capture the whole specimen

I am trying to photograph. While this system is certainly

not ideal (or even elegant), it works and I have been able

to take pictures to share on my website.

In Conclusion:

I would certainly recommend

either of these National microscopes to anyone getting started.

They are reasonably priced, easy to use and will provide a

window into a fascinating new world. (They are available at

www.microscopeworld.com)

Be forewarned, those of you

who decide to get yourselves a starter microscope. If you're

anything like me, you could become obsessed with the unseen

world and find yourself looking to upgrade your microscope

one day. As it happens, my upgrade arrived last week. It is

a used Olympus BH-2 that I bought from a veterinary pathologist.

(And, yes, it ended up being about nine times more expensive

than my National scope.) Buying a more sophisticated piece

of equipment opens up a whole new "can of worms",

as they say. You would be surprised at the variety of types

of microscope configurations available! You have to learn

a whole new set of terminology regarding lighting and optics;

then, of course, is the five hundred page book you have to

read in order to learn to use the thing. But, so far I'd have

to say the added expense and complexity has been well worth

it considering the quality of the images. (And heck, I don't

even really know how to use it yet.) However, if I had not

been using the starter scope for the last three years, I'm

not sure I would truly appreciate the resolution and clarity

of the images my new microscope provides.

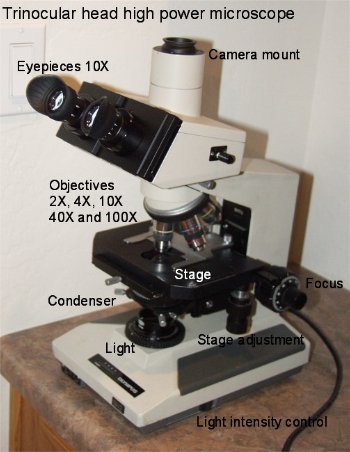

|

Now this is a microscope!

It weights over twenty pounds and has more knobs than

I can shake a stick at. I still have to purchase an

adapter for my Canon F-1 camera, so I'm shooting pictures

with the digital camera through the eyepiece. I can't

wait to be able to take proper pictures of the whole

field using the trinocular head!

|

Here's a sample of a munnid

isopod photographed through my Olympus microscope.

Awesome, huh?

|

|

|

|